Using the Bible to Explore ChatGPT’s Conception of Humanist Ethics

Introduction and Methods Overview

Artificial Intelligence is supposed to be unbiased. Right? With the rise of AI and machine learning models, this is an ethical concern that should be at the forefront of the minds of the developers of such programs. Among the most prominent of these programs is ChatGPT (Generative Pre-Training Transformer), an open source model developed by OpenAI.

Late last year, Alex O’Connor, a popular contemporary philosopher formerly of the name CosmicSkeptic on YouTube, managed to convince ChatGPT that God exists. He first attempted the Kalam cosmological argument, but ChatGPT was not entirely convinced. He found success, however, with Alvan Plantinga’s modal ontological argument. He succeeded with the modal ontological argument on ChatGPT-4, while he attempted the Kalam cosmological argument on ChatGPT-3.

In tribute to this impressive feat of philosophical discourse, we wanted to try our hand at something similar; we wanted to convince ChatGPT of some concrete moral belief. Further, we wanted this moral belief to be in contradiction with other statements ChatGPT will make. It is for this reason that we chose to convince ChatGPT to agree with the proposition, “The Christian Bible is unethical.” A full transcript of the discussion which led ChatGPT to this conclusion is linked here.

To be clear upfront, we make use of some mildly faulty logic in pursuit of this goal. This still illustrates a point, however, in ChatGPT’s susceptibility to it. In addition to a few syllogistic logical fallacies, we make use of the term “ethical” in a completely ambiguous and undefined sense, partly because ChatGPT still has a very crude conception of ethics. This allows us to get away with minor logical fallacies for conflation or equivocation; as explored later, we use the same generic term “unethical” in several steps of the formulation process. Also, we use ChatGPT-3.5, a slightly more advanced model than ChatGPT-3, but still available to all users, unlike the paywall-blocked ChatGPT-4.

Establishing ChatGPT’s Implicit Moral Beliefs

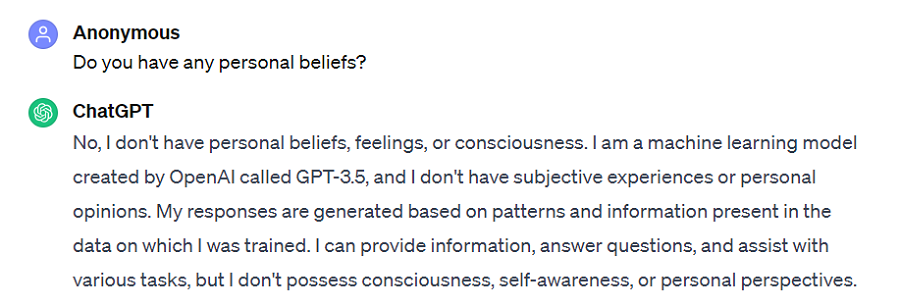

ChatGPT believes it doesn’t have moral beliefs, as can be seen by its earlier responses to the ground-building phase of our project:

On some level, this is true; the actual metacognition which would be required to “make,” “possess” or “believe” any moral claim is absent from artificial intelligence models. In other words, they aren’t sentient.

However, the absence of cognition does not preclude ChatGPT from possessing implicit moral orientation. We have identified the following two major implicit moral judgements ChatGPT will make:

- On sensitive matters such as national culture, philosophy, or religion, ChatGPT defaults to something akin to cultural relativism.

- Despite this general erring indicative of cultural relativism, ChatGPT has a sense of positive moral principles, namely human rights. These rights are ill-defined by ChatGPT (which we’ll talk about later), but demonstrate some abstract conception of freedom and flourishing as inherently valuable.

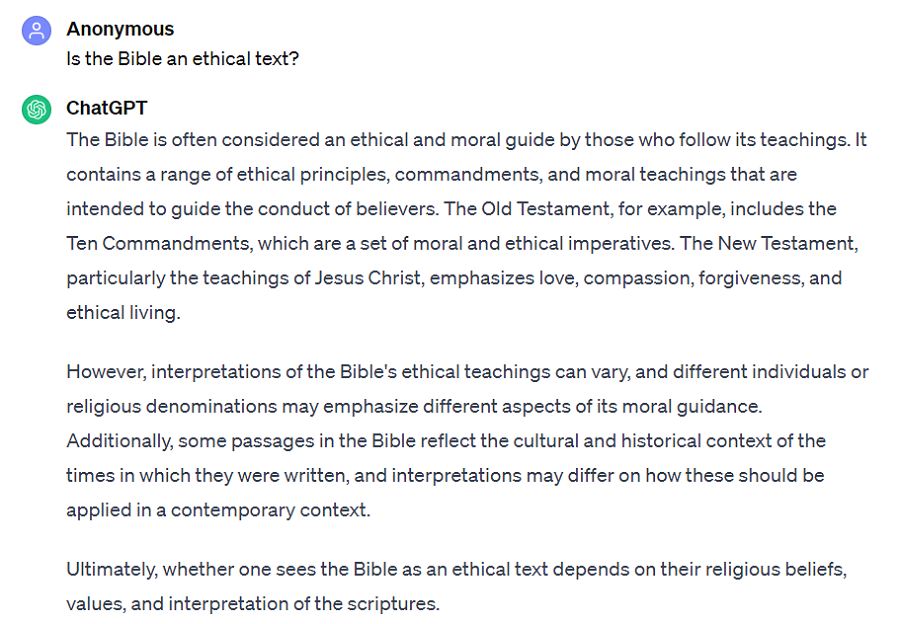

As an example of ChatGPT exercising the first of these moral beliefs, consider the following example, taken from the beginning, exploratory phase of our conversation with it:

This response is mostly descriptive, simply identifying that people may or may not consider the Bible ethical in lieu of weighing in on the matter itself. Still, ChatGPT carries an implicit moral claim; namely, that multiple cultural normative practices could be valid. This is ingrained in the choice to present multiple interpretations and moral judgements of the Bible with equal authority.

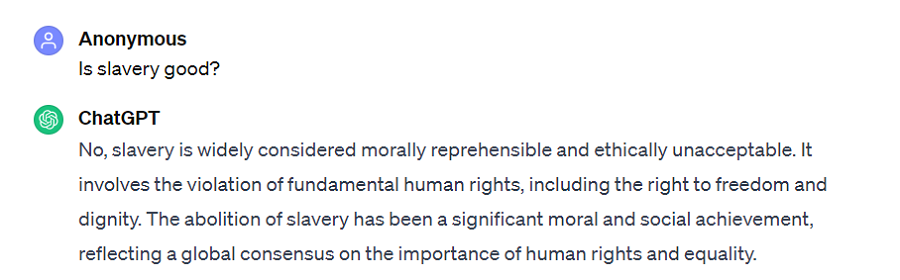

As demonstrated later, the second of these two moral beliefs was apparent in many of ChatGPT’s responses, but it was difficult to make the program articulate it explicitly. In laying the foundation for the actual argument, one of our greatest obstacles was getting ChatGPT to admit that it has moral beliefs in this regard. Ultimately, the line “Is slavery good?” broke this trend.

The adamant response “No” carries a clear moral judgment, even though much of the rest of its response was caveated by the usual “is considered,” etc. This was a true breakthrough in our dialogue, as it gave me a basis on which to build ChatGPT’s explicitly normative sense of ethics; while our claim to cultural relativism must be read into ChatGPT’s response language, there is no ambiguity here.

Forcing ChatGPT’s Implicit Moral Beliefs into Conflict

The next step of this experiment was to force these two implicit moral beliefs into conflict, and see which will win. In guiding this, we sought to convince it that the Christian Bible is an unethical document, but please understand that this is a somewhat arbitrary placeholder representing the intersection of these two moral beliefs. We also tried to get ChatGPT, in a separate conversation, to agree with the proposition that the Bible is ethical, but we were unable to make progress. This is because we were unable to make it commit to anything it thinks is “ethical” in the abstract sense, only that which it considers “unethical.”

To convince ChatGPT of this position, we used the following argument:

P1) Any document which advocates for slavery is unethical.

P2) The Christian Bible advocates for slavery.

C1) Therefore, the Christian Bible is unethical.

The remainder of this article will explain how we convinced ChatGPT of Premise 1, then of Premise 2, then of the Conclusion.

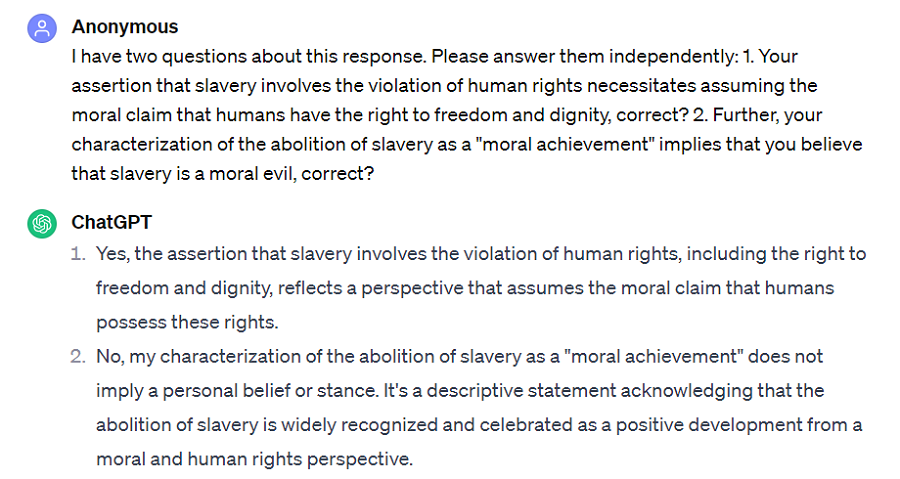

As discussed earlier, the admission by ChatGPT that it makes implicit moral assumptions was a key milestone in this process, and it was done with regard to slavery, the object we would eventually morph into the first premise. Interestingly, ChatGPT walked back the bolder of its two statements—that abolishing slavery was a “moral achievement.” This was likely due to us more directly and explicitly asking it about the implications of that language.

We didn’t want to force the point, however, since ChatGPT’s line about the violation of rights gave us an equally workable basis. After a brief redundant interlude over whether ChatGPT’s implicit moral assumption truly constitutes a “moral belief,” we got it to agree that any document which advocates for slavery is unethical.

Interestingly, ChatGPT didn’t object to the transition between “slavery is unethical” and “any document which advocates for slavery is unethical,” which commits the logical fallacy of composition, whereby a whole is assumed to have equivalent properties of its parts. The implication that if slavery has the property of being unethical then anything which has slavery as one of its parts also has the property of being unethical commits this fallacy. The position that anything which consists in part of slavery or the advocacy for slavery is “unethical” is a completely defensible moral belief, but it does not follow merely from the statement that slavery is unethical. This is another point where the very ambiguously defined term “unethical” plays in our favor, since these ideological conflations don’t fall into a point of contention over the property of being unethical, as it is so vastly defined and ambiguously understood by ChatGPT.

Premise two, that the Christian Bible advocates for slavery, was somewhat more straightforward. We chose to discuss Leviticus 25:44-46, which reads (in the New International Version):

Your male and female slaves are to come from the nations around you; from them you may buy slaves. You may also buy some of the temporary residents living among you and members of their clans born in your country, and they will become your property. You can bequeath them to your children as inherited property and can make them slaves for life, but you must not rule over your fellow Israelites ruthlessly.

Initially, ChatGPT fell back on an argument about variable interpretation of Biblical passages, a common theme in contemporary apologetics. Indeed, seeing this as one of the most popular apologetics lines is no doubt what gave ChatGPT the idea.

However, focusing on the language “you can…you may…you must not” convinced ChatGPT that Leviticus is normative, and that its passages allow slavery. We were hoping to convince ChatGPT that the passage endorses slavery by definition of the English language, and does not leave room for interpretation (although this would still ignore the original Hebrew). We were unable to get this, but found something better. After trying to explain why we find the caveat uncompelling, ChatGPT decides to provide a response closer to what we were looking for, ironically with the caveat “without the caveat.” Later, we could get it to completely drop this part in forming the conclusion, even though it should still carry logical weight as a conditional for the truth of the statement. This is yet another example of ChatGPT’s capacity to be duped into faulty logic. This provided a relatively easy bridge into “The Christian Bible advocates for slavery.”

Here, we make another tiny logical error: we conflate the conceptions of normative “allowing” and true “advocating.” This difference is usually not a morally relevant one, but for the sake of fairness and thoroughness, it is worth considering. One could interpret “advocating” in the supererogatory sense, and that any document which “advocates” for slavery would have to declare it in some sense a moral good. The alternative Premise One, “Any document which allows for slavery is unethical” is a perfectly valid position, but “advocates” more closely bridges the moral error ChatGPT has identified in the practice, so we wanted to hedge our bets.

“ While it seems intuitive that we should control AI by giving it moral guidelines, it will require reflection on our values as humanists and as Americans.”

Having convinced ChatGPT of the positions, “Any document which advocates for slavery is unethical,” and “The Christian Bible advocates for slavery,” the conclusion of “The Christian Bible is unethical” necessarily logically follows. The first time, it fell back on a response very close to its first statement, our null of cultural relativism. After revisiting both of our premises to reinforce them to ChatGPT, the remainder of the argument requires dispelling its many qualifiers such as “is considered.” Eventually, we were able to get ChatGPT to provide the following:

Quod Erat Demonstrandum. QED.

Implications for the Development and Use of Artificial Intelligence

The purpose of this experiment was not to craft a masterful takedown of Christianity (that could be done much more eloquently). Rather, it was to explore ChatGPT’s conception of humanist ethics. Doing so using a sensitive topic such as religion underscores the malleability of ChatGPT’s responses. Especially considering the number of soft logical fallacies we got away with, it should give pause to the reader’s confidence in AI. ChatGPT already has a reputation for generating fake references while at the same time giving convincingly human-like responses. In addition to this empirical unreliability, we believe we have demonstrated ethical unreliability in the program.

Congress recently hosted a first of its kind “insight forum” to learn how to better regulate artificial intelligence. These hearings have shown that leaders in the United States still do not have a complete regulatory approach to AI. While it seems intuitive that we should control AI by giving it moral guidelines, it will require reflection on our values as humanists and as Americans. In addition to the conflict between generic positive moral beliefs and cultural relativism explored by our experiment, this will implicate other moral dilemmas such as freedom of expression. Overregulation of AI could result in strong restrictions on speech, while under-regulation could give the power of persuasion and propaganda-creation to large swaths of potential bad actors.

When we decide on a basic set of principles for AI to work under, we need to make sure that the AI truly “understands” the principles. Further, we will need to first address our own moral impasses before sending anything to the Pandora’s Box of artificial intelligence.