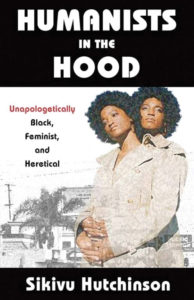

Humanists in the Hood

BY SIKIVU HUTCHINSON

PITCHSTONE PUBLISHING, 2020

While growing up as a precocious young girl in South Los Angeles, Sikivu Hutchinson observed startling misogyny, racism, religious bigotry, economic injustice, housing inequality, and other forms of injustice in her community. These experiences shaped her consciousness and set the tone for her life of radical humanism, intersectional feminism, intellectual development, and grassroots activism. Humanists in the Hood is a product of her life’s work and experiences. In this book, she sets out to, “explore the promise of intersectional, Black feminist–identified approaches to humanism that are grounded in the everyday realities of living in hyper-segregated communities of color.”

Hutchinson begins by describing the historical conflict between White feminism and Black feminism. She lays bare the reality of Black women who have been turned off by the feminist movement and the toxic White supremacy within it. Hutchinson’s historical analysis shows us that Black freethinkers and humanists have been fighting for justice for more than a century, and their contributions to humanism should be studied and respected by present-day humanists.

Hutchinson outlines the numerous existential struggles of Black feminist humanists who are bombarded by racism, classism, economic exploitation, disenfranchisement, dehumanization, and abuse from the White world. These Black women are fighting multiple battles on as many fronts simultaneously. They feel isolated in their own communities because of their atheism, and at times they are accused of being ‘inauthentically Black’ because of it. They are often forced into domestic work at an early age, stuck in low-wage, nonunionized jobs to support themselves and their families. They do not receive adequate support from the humanist community, and many of them do not have the time or access to the mental health resources they need for self-care, recovery, and healing.

Sikivu Hutchinson

Hutchinson correctly points out that present-day humanism has failed to live up to the vision of past leaders—i.e., Paul Kurtz, Edwin Wilson and others who signed the second Humanist Manifesto of 1973—in addressing social and economic injustice. Some present-day humanists in the United States focus exclusively on matters concerning the separation of church and state and critiques of religion while neglecting other crucial areas. When Black humanists call attention to the economic and socio-cultural issues affecting communities of color, they are attacked, marginalized, ignored, or branded as social justice warriors, snowflakes, or worse. Hutchinson calls out this behavior and the surprise expressed by these same humanists when people of color aren’t interested in joining their communities. Simply put, if White humanists want to attract more people of color to humanism, then White humanists must be invested in the issues that affect the daily lives of the disenfranchised. Hutchinson’s critique of the humanist movement’s misplaced priorities and neglect to engage these socio-cultural and economic issues is necessary and apt.

Hutchinson acknowledges the merits and positive contributions of religion to the Black community while simultaneously critiquing its downsides and negative impacts. She explains how religion and faith-based organizations have played an important role in developing communities of color by providing diverse services including community supports and protections, financial support, social welfare, educational services, career development, mentorship, recreation, and political activism. Many young people of color depend on services provided by these religious institutions because they cannot get them anywhere else. This dependency makes it difficult for them to leave their religious communities and abandon their beliefs, even when they see the problems within these religious systems.

Hutchinson subsequently critiques the sexism, racism, homophobia, transphobia, political authoritarianism, and respectability politics that are endemic in religion and reveals how it damages the lives of people of color. She shows how religion’s focus on eternal life as the end goal and the dependence on god through prayer devalues our present lives and damages our self-determination. She argues that humanism presents a better way for us to live our lives, build our communities, and fight for justice while being grounded in realism.

Hutchinson also calls attention to the need for activism in education, arguing that humanism should not just be focused on curtailing religion in schools, but also on ensuring that people of color and the LGBTQ+ community are accurately represented in children’s literature. Hutchinson challenges the lack of Black humanist secular content in American media, the arts, and academic scholarship which she purports are dominated by religious and White-centric perspectives. There is a scarcity of intersectional scholarship that employs diverse humanist frameworks. Humanism needs to be present in these spheres because literature, scholarship, art, and entertainment shape how we view ourselves, our communities, and how we make sense of the world. Including these frameworks helps minimize the social stigmas surrounding atheism and humanism, dispel toxic worldviews, and empower people to effect social and economic change. These are humanist concerns as much as the separation of church and state.

In the final chapter, Hutchison addresses the phenomenon of the “nones,” which refers to the increasing generations of Americans who identify as nonreligious. Hutchison rightly cautions against presupposing that this cultural shift presents an automatic victory for humanism. She warns that the Religious Right is still a potent force to be reckoned with and will continue to use its power to influence the legal system, public policy, politics, reproductive rights, environmental laws, and the education system. Time will tell if the “rise of the nones” will lead to a national shift toward humanist values or simply toward the abandonment of organized religion.

Hutchinson highlights some hopeful trends in the Gen Z demographic: they are more likely to identify as atheists than previous generations, they question religious dogma and ask for factual evidence to support religious claims, and they are more willing to embrace varying gender and sexual identities and gender roles than past generations.

However, these trends are more complicated in the Black community. Black youth are more likely to attend church and read the Bible than their non-Black contemporaries and are also more likely to embrace the idea that the Bible is the literal word of God than other ethnic groups. Black youth are not retreating from organized religion the same way non-Black populations are. And despite some positive trends regarding humanist values and intersectionality within the Black community, there is still a cultural tendency to position these shifts within Black American theological frameworks.

Hutchinson considers how these generational changes intersect with humanism, feminism, gender identity and nonconformity, economic justice, and mental health in communities of color. This leads to one of the most important aspects of Humanists in the Hood. Hutchison reaches out to the next generations, welcoming them into the humanist community, teaching them that humanism is relevant to their identities and daily struggles against injustice and oppression. The question White humanists must ask is, “are we ready to do the hard work of welcoming people of color and creating an environment that includes and supports them?” Hutchinson’s book is both a wake-up call and a call to action for all humanists.

Humanists in the Hood is a short read and is written in a straightforward style that the average, non-academic reader can understand. It is well-researched, intellectually sound, intersectional in its analysis, and filled with useful practical insights. One of the major strengths of the book is its pragmatism. At the end of each chapter are suggested action steps and recommended readings which, alone, are worth the price of the book.