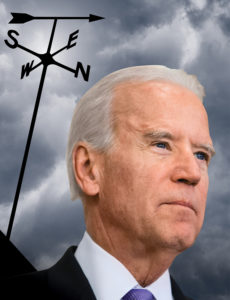

Joe Biden: The Weathervane and the Storm

If margins make a mandate, President Joe Biden has the largest mandate of any elected president in US history. He won the largest vote total of any presidential candidate, the largest vote total relative to population, and the largest vote percentage of any non-incumbent presidential candidate since Franklin Delano Roosevelt in 1932.

But the question is, what is Biden’s mandate? Is it a repudiation of Donald Trump? Or of the Republican Party’s catastrophic handling of COVID-19? Or of the status quo more generally? Of everything from the Electoral College to the tyranny of bondholders when it comes to government spending?

Biden has been a weathervane his entire political career. But now no one seems sure which way the wind blows. No one, that is, but Biden himself.

While opinion-makers licked their thumbs trying to get a grip on where things were moving, Biden was pointing the way his entire campaign. In his speech at the Democratic National Convention in August 2020, he said we find ourselves in the midst of “four historic crises. All at the same time. A perfect storm.”

The four crises, according to Biden, are the COVID pandemic, the looming economic depression, racism, and climate change. And he proposed solutions for all four: a national mask mandate; cash for employees and employers if businesses need to close for another lockdown; a fifteen-dollar minimum wage; a pro-family policy package including universal preschool, in-home care for the elderly, a public option for Medicare, and lowering the Medicare age from sixty-five to sixty; a national standard for police use of force and a “reigning in” of “qualified immunity”; and a $2 trillion dollar green infrastructure bill.

All these policies are clear and concrete. So why the uncertainty about what Biden’s victory meant? Some argue that because many votes for Biden were really votes against Trump, the mandate was for Trump to leave not for Biden to change anything. But never are all of a candidate’s votes purely an endorsement of their platform. Every election has anti-candidate votes. Abraham Lincoln in 1860 received anti-slavocracy votes. FDR in 1932 got anti-Hoover votes. And Lyndon Johnson in 1964 got anti-Goldwater votes. That didn’t stop these presidents from doing what needed to be done. And anti-Trump votes shouldn’t stop Biden either.

Others, however, argue that the uncertainty (or cynicism) about Biden is simply based on his political record. A political record that, to be fair, doesn’t inspire much hope. As journalist Ryan Grim wrote, “Biden’s contribution to the party debate has been to put himself on the wrong side of the issues with a startling consistency. One would think that just by chance, given a career that spans a half-century, he’d manage to get a few things right by accident.”

On everything from busing to the 1994 crime bill, to the repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act to the Iraq War, Biden has been wrong. In addition, he voted for the “performance pay” loophole in the bill that limited the tax deductibility of executive salaries but excluded “performance-based compensations.” So companies began gifting executives bonuses and stocks, then turning around and buying the stocks back—inflating stock prices and allowing executives to take from businesses money that should’ve gone to wage increases and institutional improvements.

Which is again to say that Biden is a weathervane—he has gone where the country and the Democratic Party have gone. And, over the last fifty years, the country and the Democrats have gone to some horrible and pathetic places.

But things change. Conditions change. And so do our responses to them. And so too does our tolerance for non-responses.

In These Times

About one third of Democratic voters wanted Senator Bernie Sanders to be the party’s presidential nominee, and many of Biden’s own voters supported Sanders’s policies. For example, in primary states where Biden won decisively, a majority of voters also said they wanted Medicare for All—a defining policy of the Sanders campaign that the Biden campaign opposed. An opposition well understood by the economic elite. After Biden won ten of the fourteen states on Super Tuesday, health insurance stock prices increased.

During the Democratic primary, Biden was seen as the moderate foil to Sanders’s populist insurgency. And this wasn’t incorrect. After Sanders won the first three primary states, the party establishment mobilized for Biden in comically sinister ways. Therefore, from the perspective of the Sanders wing of the party, Biden’s nomination promised nothing but a non-Trump presidency—a return to the status quo that created the conditions for a Trump presidency in the first place.

Biden feels the need to be at the center of the Democratic Party rather than at the center of the entire country’s political spectrum. He sees himself as a figure like Lincoln in 1860: not as the moderate candidate of his country but as the centrist candidate of his party.

However, while the Sanders campaign was not effective in winning the nomination, it was effective in making demands on the party. Demands the party, including Biden, could no longer ignore. As New Yorker writer Evan Osnos wrote in his biography of Biden, Joe Biden: The Life, the Run, and What Matters Now, “In the usual course of a presidential campaign, a Democrat leans left during the primary and then marches right in the general election. Biden went the opposite direction.”

Biden and Sanders established joint task forces with the purpose of alchemizing the two candidates’ platforms. While task forces are where policies go to die, the gesture is still more than the Sanders wing got in 2016, when it was met with hostility and shunning.

This is because Biden feels the need to be at the center of the Democratic Party rather than at the center of the entire country’s political spectrum. He sees himself as a figure like Lincoln in 1860: not as the moderate candidate of his country but as the centrist candidate of his party.

During the election, Biden routinely invoked Lincoln (as well as FDR and LBJ) in his speeches. But Lincoln, FDR, and LBJ were our country’s most radical presidents while Biden was the moderate foil to a radical candidate. What changed?

For one, the circumstances. One of the worst handlings of the pandemic anywhere in the world—food lines, homelessness, unemployment, back payments on rent and mortgages, crowded hospitals, and hundreds of thousands dead.

As Biden said in his DNC speech, we are at an “inflection point.” Just as we were when Lincoln, FDR, and LBJ each took office. Ever the weathervane, Biden seems to understand that the moderate-radical dichotomy only holds in calm weather, in peacetime. And that is not where we find ourselves.

Biden once told a story about a Christmas party at the car dealership where his father worked as a salesman in which the dealership owner threw a stack of silver coins on the dance floor and watched and laughed as his employees scrambled to pick them up. Biden’s father took his wife’s hand and left. All of politics, and all of how Biden needs to think and act as president, can be found in that story. In it we find another example of what Lincoln called “the eternal struggle” between “the common right of humanity” and “the divine right of kings.”

“A Man of Constant Sorrow”

That was how former Senator Harry Reid once described Joe Biden. (Reid borrowed the phrase from a song by folk musician Dick Burnett.) Biden’s life has been full of heartbreak. His oldest son, Beau, died from a brain tumor at the age of forty-five. Biden’s other son, Hunter, has lived a life of corruption, drug addiction, and petty indulgence. After his first run for president in 1988, Biden was discovered to have a cranial aneurysm that required immediate surgery. The doctor warned him he might never be able to speak again, a cruel fate for a man who overcame a childhood stutter. It took him seven months to recover and in his first speech back he told the audience he felt like he had been given a “second chance in life.”

That was how former Senator Harry Reid once described Joe Biden. (Reid borrowed the phrase from a song by folk musician Dick Burnett.) Biden’s life has been full of heartbreak. His oldest son, Beau, died from a brain tumor at the age of forty-five. Biden’s other son, Hunter, has lived a life of corruption, drug addiction, and petty indulgence. After his first run for president in 1988, Biden was discovered to have a cranial aneurysm that required immediate surgery. The doctor warned him he might never be able to speak again, a cruel fate for a man who overcame a childhood stutter. It took him seven months to recover and in his first speech back he told the audience he felt like he had been given a “second chance in life.”

All those heartbreaks, however, pale in comparison to the tragic death of his first wife and baby girl in a car crash when Biden was only twenty-nine. It happened just a month after he’d been elected to the US Senate. He considered not taking his seat. Then he thought about suicide. But a group of senators convinced him that working would be the only way he’d get through what happened. He was sworn into the Senate standing beside Beau’s hospital bed. (Both his sons were in the car crash as well; Hunter suffered a head injury, Beau broke a few bones.)

Compared to the death of one’s wife and baby girl, a political betrayal can hardly seem worth mentioning. But reading Biden’s 2017 memoir, Promise Me, Dad: A Year of Hope, Hardship, and Purpose, one can tell Obama’s treatment of Hillary Clinton as the party’s heir-apparent hurt Biden. It would’ve been one thing for Obama to stay on the sidelines for the 2016 election, but he effectively benched Biden.

Biden was angry about the election, especially after Clinton lost. He felt he could’ve easily beaten Trump. His plan was to run a populist-type campaign. In 2014 he said to Osnos, “Why the hell aren’t we talking about earned income versus unearned income?”

Biden also sensed, in a way Clinton didn’t and Trump did, that in 2016 the country was fatigued by war, if not also fatigued by empire. In cabinet meetings during the Obama Administration he was the “dove” to Clinton’s hawkishness. He opposed the assassination of Osama bin Laden and the intervention in Libya and blamed our allies for the disaster in Syria. He said Turkey and the Gulf States had turned an anti-Assad insurrection into a geopolitical proxy war by funding, arming, and mobilizing Sunni fundamentalists. To Biden’s credit, he rejected the Cold War mentality of fighting little countries as proxy wars against geopolitical rivals. He believed (and I hope still believes) that such spilling of blood is wrong and counterproductive.

Spread the Faith

Biden is a devout Catholic and probably the most religious president we’ve had in fifty years. He isn’t a fundamentalist. He doesn’t weaponize religion to divide people, nor does he use it as a political sideshow to distract from progress. It neither numbs nor perverts his morality. It inflames it. And his religious faith is tethered to all his other faiths—his faith in democracy, his faith in progress, his faith that when things must be done we as a country are capable of doing them.

Of course, as a Catholic, Biden knows that faith alone is not enough. As the Bible says, “Faith, if it hath not works is dead.” Everyone remembers FDR’s famous remark, “We have nothing to fear but fear itself.” But that was only the beginning of the sentence. The full remark was, “We have nothing to fear but fear itself—nameless, unreasoning, unjustified terror which paralyzes needed efforts to convert retreat into advance.” The Democrats for decades have been in retreat. And so has the country. That must end. There must be work. Otherwise our country’s faith in itself will continue to wither. And eventually die.

There is much reasonable uncertainty and skepticism about Biden. To have defeated Trump is not enough. The condition that brought Trump about must be defeated. Otherwise, we might not be so lucky the next time a would-be dictator is so corrupt, incompetent, and feckless. And make no mistake, Biden contributed to creating the conditions that led to Trump. As Osnos wrote, the 2020 election was “a referendum not only on Trump’s moral fitness, but on the architecture of American power—a system that Biden had helped develop and refine over half a century in public life.”

Regardless of his intentions, Biden will find himself to be a president with limited tools to work with. The mechanisms of society are geared against progress. With the Senate, the Electoral College, judicial supremacy, at-will employment, no representation for employees on boards of directors or in electing their own managers, we already don’t merit calling ourselves a democracy. And this election the Republican Party flirted with no longer even bothering to pretend the country should be one. What’s more, the Democratic Party’s leadership is a conservative gerontocracy: House Speaker Nancy Pelosi is eighty, Majority Whip Steny Hoyer is eighty-one, Majority Whip Jim Clyburn is eighty, Biden himself is seventy-eight, and Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer is the young gun at seventy.

This is a lot for any president to take on, much less a president with Biden’s checkered political record. But there have been signs of growth. Obama’s failures at bipartisanship changed Biden, and so did the death of his son, Beau.

In the closing of his presidential victory speech, Biden told a story from his childhood. He said when he used to leave his grandparents’ house, his grandfather would say to him, “Keep the faith”; and his grandmother would correct him, “No, Joey, spread it.” One must hope Biden follows his grandmother’s guidance and spreads the faith. The faith in democracy. The faith in progress. And that he remembers the central tenet of his Catholicism: that faith without work is nothing.

Otherwise the storm we find ourselves in will become more violent and more dangerous. It will destroy the crops and uproot the trees and blow down the houses. Then there will be no need for weathervanes. Because it will no longer matter which way the wind blows.