Nonreligious Americans: the Key Demographic That No One Is Talking About

In the wake of Joe Biden’s victory in the November 2020 presidential election, many constituencies were credited with tipping the balance in his favor, including black Americans (particularly black women), young voters, and even Navajos in Arizona.

But often lost in such discussions is another, much larger and growing demographic: nonreligious Americans.

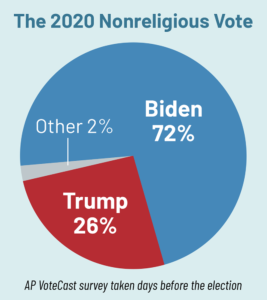

According to the AP VoteCast survey taken a few days before the election, nonreligious Americans (those answering “none” to the question of their religion and who make up 21 percent of voters) overwhelmingly planned to vote for Biden at 72 percent compared to 26 percent for Donald Trump. If on further analysis these numbers prove accurate, the so-called “nones” will have added roughly 21 million votes to Biden’s total and only 7 million to Trump’s, a difference far greater than the more than 7 million votes that secured the popular vote for the former vice president.

The support for Biden among the nonreligious was stronger than support for Trump among clearly defined religious groups such as Protestants, who leaned strongly toward Trump (61 percent), and Catholics, who narrowly supported Trump, 50 percent to 49 percent (although other exit polls gave Biden a slight edge among Catholics.) Surveys and exit polls often don’t consistently break down religion by race, but one demographic that pollsters were keenly observing was white evangelical Christians, given their outsized importance in the Republican coalition. According to the AP survey, this group (22 percent of voters) backed Trump 81 percent to 17 percent.

White evangelicals have been a rock for Trump, who rewarded their loyal support with executive orders on “religious freedom,” court appointments, and symbolic gestures signaling his endorsement of Christianity. Given their comparable size as a percentage of the population (21 percent of voters are nones while 22 percent are white evangelicals), American nones have the potential to become a voting bloc on par with white evangelicals in size and influence, particularly if one party were to court them and advance their interests, as Republicans have done for their white evangelical base.

Overall, the nonreligious—atheists, agnostics, or no religion in particular—make up 26 percent of the American population according to a 2019 Pew Research Center survey, a significant increase from 17 percent in 2009 and slightly higher than the aforementioned 21 percent of likely voters. These gains are coming at the expense of Protestants and Catholics, whose respective numbers have declined in the same period from 51 percent to 43 percent of the population, and 23 percent to 20 percent, respectively. Furthermore, nones make up an increasingly larger percentage of young people: 40 percent of millennials (those born between 1981 and 1996) report no religious affiliation while only 49 percent of millennials are Christians.

Research and current trends point to continued growth among the nones. The sociologist Linda Woodhead, in her research tracing the rise of nones in Britain, found that nonreligion is “sticky”: people who were raised as a none had a 95 percent chance of remaining a none while those raised Christian only had a 55 percent chance of remaining Christian. This trend seems to be unfolding similarly in the United States—borne out in the decline in church attendance, which suggests people are departing the religious communities they were born into but not converting to a different religion. In the coming years, this change will be compounded by other demographic factors. As older, more religious generations die out, they will be replaced by the younger, more irreligious millennials. These changes have already reduced the once-dominant Protestant majority to a minority. All this suggests not simply a waning religious population over time but a potential future with a permanent Christian minority that must contend with an increasingly secular electorate that doesn’t necessarily share their interests.

This divergence in interests is already playing out in our politics. To take one example, in November 2020 a new law passed by the Washington state legislature that required public schools to provide comprehensive sex education was subject to a veto referendum on the ballot. A vote in support of the measure would have allowed the law to stand, while a vote against it would have overturned the law. Right-wing groups managed to get the initiative on the ballot by gathering more than double the necessary signatures. More than two-thirds of the 264,000 signatures came from drives at church sites. But Washington has a high population of nones (34 percent), and an even higher number of citizens who never attend religious services (45 percent). Religious objections to the sex-education law did little to sway nonreligious voters and may even have had the opposite effect. Accordingly, the law was affirmed when the measure passed overwhelmingly in the state.

Nones will likely awaken politically as court decisions and legislation continue to privilege religion. In 2017 the Trump administration began to expand “religious liberty” to allow religious exemptions from anti-discrimination laws, making it lawful to use federal dollars to discriminate against religious minorities, including nones. This is not an extension of liberty that goes both ways—religious groups have the right to discriminate while providing services to citizens, but nones do not have the same right to discriminate against the religious. This hierarchy of rights creates clear in-groups and out-groups. Consider the example of religious exemptions in the Affordable Care Act that allow employers to refuse birth control coverage to employees. In this case, nonreligious people (and religious people as well) can be denied benefits based on the particular religious convictions of their employers.

In 2009, just 10 percent of Republican supporters were nonreligious whereas by 2019 this number had climbed to 16 percent—an increase of more than 50 percent in a decade.

As court rulings and legislation on religious liberty weaken the separation of church and state, this will likely increase the tensions between the nones and the religious, and potentially motivate more nones to organize to exert political pressure on policymakers. This is already beginning to happen. In November 2020, the Secular Democrats of America (SDA) delivered a 28-page policy paper of demands to then President-elect Joe Biden. In it, they argued that the Trump administration actively fostered a radical Christian nationalist agenda that allowed religious organizations to use state funds to roll back anti-discrimination legislation. The Secular Democrats also offered policy prescriptions, such as ensuring enforcement of the Johnson Amendment—a law that prohibits tax-exempt nonprofits, including churches, from endorsing candidates—a statute that the Trump administration instructed the IRS not to enforce. Of course it remains to be seen if Biden, a strong Catholic who frequently refers to his faith, will follow these suggestions.

As the Washington Post reports, nones generally hold many progressive views on abortion and LGBT rights:

Religiously unaffiliated voters are generally pro-choice: Seventy-four percent think abortion should be legal in “all/most” cases, according to Pew. Seventy-two percent of unaffiliated voters oppose “allowing a small business owner in [their] state to refuse to provide products or services to gay or lesbian people if doing so violates their religious beliefs,” according to the Public Religion Research Institute, and 79 percent favor same-sex marriage, Pew reports.

This helps explain their strong support for Democrats in the past two elections.

Despite all this, the Democrats have yet to pay direct attention to the nonreligious as a potential voting bloc. Biden’s election acceptance speech was full of religious language, indicative of his own religious faith. He said that “we embark on the work that God and history have called upon us to do,” and closed with the obligatory, “God bless you. And may God protect our troops.”

Nonreligious people have typically accepted this kind of religious language, knowing it is a necessary part of politics in the United States. But one wonders whether such God talk will sound increasingly out of place as nonreligious people make up more and more of the electorate.

Still, it isn’t a law of nature that nones will continue to vote Democrat, especially if their political interests continue to be ignored. While nones make up a growing percentage of the Democratic base, given the rise of the nones across American society as a whole, it is important to note that the share of nonreligious Republican voters has also risen. In 2009, just 10 percent of Republican supporters were nonreligious whereas by 2019 this number had climbed to 16 percent—an increase of more than 50 percent in a decade. The nonreligious are a growing base of voters that could in theory be captured by either party. It follows that changes in the makeup of both parties—a decrease in religious members and an increase of nones—has the potential to shift the parties’ policy goals and platforms.

Currently, this group of nones votes overwhelmingly Democratic with political interests that lean away from the religious right and toward progressive stances on issues. However, nones’ views are also more likely to be comparatively diverse and not as fully formed as those of white evangelicals since they lack institutional structure. There have already been attempts to shape this secular voting bloc and ascribe it with a defined political agenda, coming from both the left and the right.

From the left, the Secular Democrats of America’s release of a policy agenda is the most recent attempt to make the desires of the nones heard by major political actors. Another Secular Democrats of America initiative, called Humanists for Biden, was chaired by Greg Epstein, a humanist chaplain at Harvard and MIT, and endorsed by many prominent secular voices. In 2014, David Silverman, a conservative and then-president of American Atheists, appeared annually at an exhibition booth at the Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC) until he was finally rejected in 2018. Other well-known secular personalities like Sam Harris and Sarah Haider openly backed Biden but were critical of progressive policies and so-called “wokeness.” Other secular figures, for example Dave Rubin and Ayaan Hirsi Ali, expressed support for Trump. Clearly multiple voices are attempting to mold the politics of the nones and broadcast their interests to the major parties. It remains to be seen whether the parties will listen.

In the 2020 election, nones represented an important faction in Biden’s successful coalition and revealed their immense potential for the future. Identifying critical issues, messaging, and mobilization of nones as a bloc will be essential if Democrats hope to win again in the future.