An Examination of Policy Views by Race & Religion

IN SPACES OF NONTHEISTS, it is not unusual to hear a question along the lines of: does it make sense for Black Americans to have separate spaces along with or even within organizations that are open to all? This question assumes, among other things, that across racial lines, nontheists reason and think similarly. Implicit in posing the question is the assumption that it is not a priori clear that the answer to a fundamental question on religion should mean that there will be similar views over other questions. Is this implicit assumption consistent with responses from recent survey research?

Public opinion polls focusing on the November 2020 election are now available to researchers. One of the more well-known of these is the continuing series of the American National Election Studies (ANES). The survey was created to research political behavior and contains a wide range of questions including those dealing with religion, race, attitudes and other issues. A preliminary version of the ANES survey was released in spring 2021.

Self-Identified Religion (and Validation)

The ANES survey is large, with about 8,300 respondents, and it is primarily concerned with political behavior, but it does include questions about religion, since religious identity is well-known to be associated with partisan voting behavior. This article focuses on ANES because, in addition to its size, the survey was constructed as an equal probability sample. It is also widely available. There are numerous other surveys about American religious behavior, including Pew Research Center and Public Religion Research Institute (PRRI). Information from ANES corresponds with these frequently cited surveys. There have also been recent surveys specifically on the views of nontheists. The Secular Survey (available at secularsurvey.com) and Ryan Burge’s findings in his book The Nones: Where they Came From, Who They Are, and Where They are Going, both present information on the views of nontheists.

Atheists, agnostics and the non-religious— the so-called “Nones”— represent 21 percent of the respondents, the second largest group behind Protestants.

The first step is to check to see if the ANES responses regarding religious issues are similar to that of Pew. This is considered a test for validation of the ANES survey with respect to this variable. Let’s consider the larger denominations: ANES shows three denominations which each represent over twenty percent of Americans. Within the ANES Roman Catholics are around twenty percent of respondents which is consistent with what is known from Pew. The percent of the population that is Catholic has remained relatively stable for decades and that continues now after combining Hispanic and non-Hispanic believers. The responses for Protestants in ANES are a little low relative to conventional reasoning, but this is explained below.

The combined values for atheists and agnostics are around ten percent which is consistent with Pew. We expect about another ten percent not identifying with any religion. However, ANES responses in that category are a bit higher than in Pew’s survey. The combination of these last three groups is conventionally referred to as “Nones”—those with no religious affiliation.

Fortunately, ANES asked a follow-up question of those who describe their religion as nothing in particular. Roughly one-third of those respondents identify as Christian. Those respondents likely correct for the apparent under-count of Protestants in ANES compared to Pew. With that correction the percent of nontheists is in the lower 20s. This is consistent with Pew surveys. It is also a cautionary tale as a substantial number of those who do not identify with a specific denomination nevertheless self-identify as Christian.

The remaining two-thirds of the “nothing in particular” are typically classified with atheists and agnostics. From a statistical standpoint, even as recently as two decades ago the number of those identifying as nontheists was so small that it made sense for surveys of the electorate to exclude them. Although not the task of this article, it may be worth seeing if the sub-groups are different.

Combine atheists, agnostics and those who say something else, but who are nontheists in one group called Nones. This group represents 21 percent of the respondents. Nones are the second largest group behind all Protestants, slightly larger than Catholics.

Black Views

Now, we turn to the concerns of the Black electorate. Of the 8,200 responses to ANES, there are 726 who identify as Black, non-Hispanic, and 271 who identify as several races. Looking only at the former, those who identify as Black, there are ninety-five Black respondents who are without a religion (thirteen percent of Black respondents), but a surprisingly small number who identify as both Black and atheist. Why would this be?

ANES has a question that asks how important religion is to the respondent. If we compare Black and white respondents on this variable it is clear that in the population as a whole, the typical Black respondent, in the entire survey, sees religion as more important than the typical white respondent. For example, twenty-six percent of white people surveyed see religion as “extremely important” whereas the figure for Black people surveyed is forty-four percent. It is apparent that Black respondents, in general, are in a community that is more religious and hence a person identifying as an atheist makes themselves much more of an outsider than in the white community. It is likely that the respondent’s community will influence the behavior of the typical Black person identifying as a None. There are further broad influences from historical circumstances for members of the Black community because of segregation, red-lining, and employment discrimination, for example, which could easily affect people’s world view as well as attitudes on policy issues.

To return to our original question: To what extent does the ANES identify different attitudes across races? It is not surprising to find similarity regarding questions of religion, since Nones among both Black and white communities might be expected to have similar outlooks. On the other hand, we very clearly see that the two communities are in some sense different just in terms of the religiosity of the communities. We should not be surprised if other characteristics are different as well. We might expect there are different characteristics in Black spaces, white spaces, and mixed spaces.

Direct Comparison

Given that both white and Black Nones have similar views on religion, we expect some similarity in positions across race on issues that might have some bearing on science or First Amendment rights. These ideas would likely be a part of the belief structure of Nones regardless of racial identity. On the other hand, there is no guarantee that we should expect a similar response across other issues. The ANES shows us that there is no guarantee that responses will be similar across other issues.

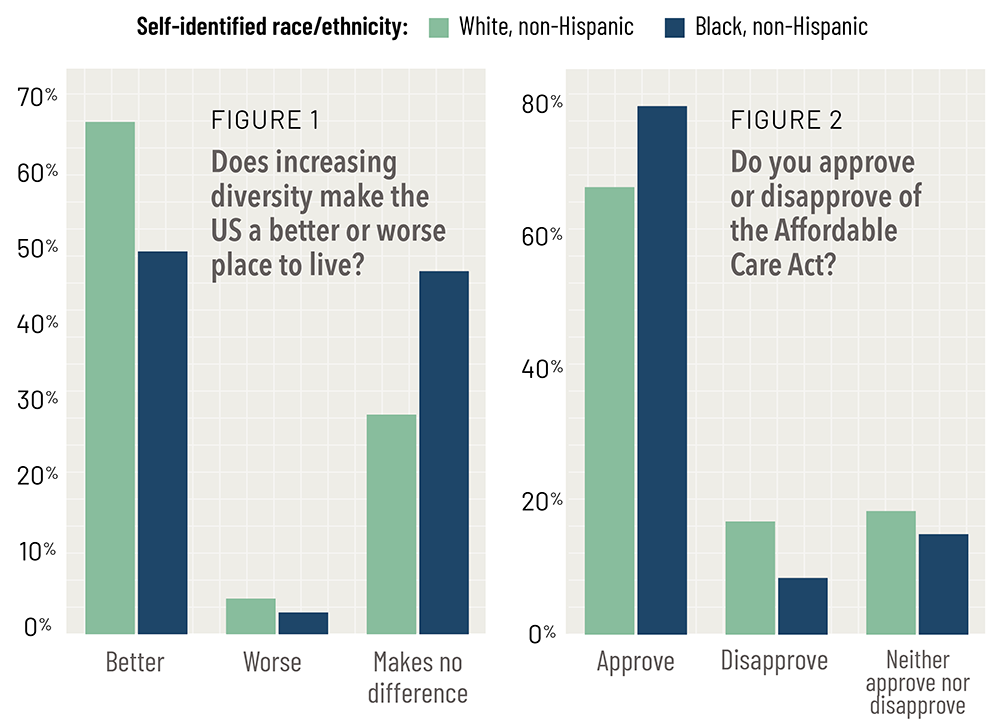

One ANES question asks about the desire to achieve diversity. White respondents are more optimistic about diversification (see Figure 1).

Another question asks about approval of the Affordable Care Act, often referred to as Obamacare. We see that Black Nones are more likely than white Nones to approve of the Act, although clear majorities of both approve (see Figure 2).

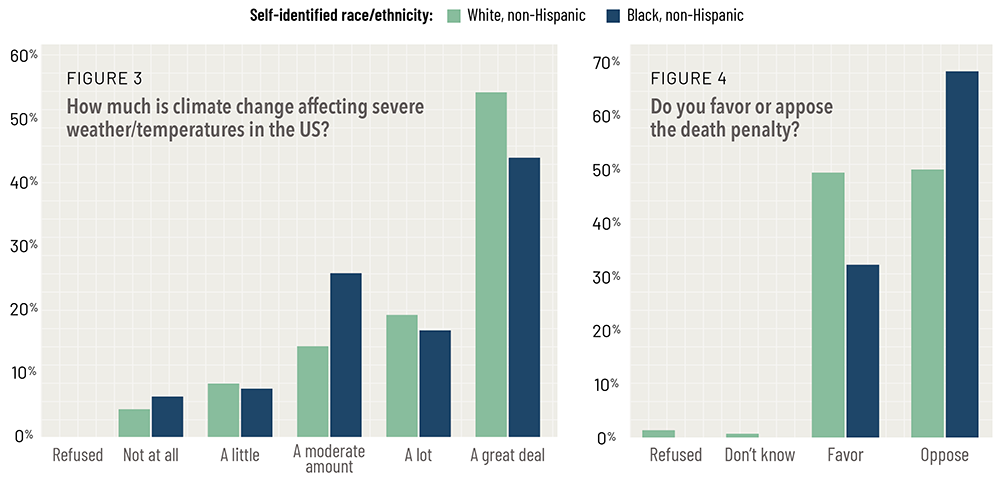

Both Black and white Nones are concerned with climate change, but whites are more likely to think the issue is more important. The views do differ on this issue, although clear majorities of both groups see climate change as a factor affecting severe weather and temperatures (see Figure 3).

However on many other social issues there are sharp differences in attitudes between Black Nones and white Nones. To give just one example, with respect to the death penalty, Black Nones are much more likely to oppose the death penalty when compared to their white counterparts. The difference is statistically significant. This response likely reflects attitudes similar to that in the general population rather than ideas associated with religion, since the difference appears on numerous other policy issues (see Figure 4).

Conclusion

The ANES survey focusing on political views in America in the autumn of 2020 has numerous variables that can be used to look at attitudes. Among those we identify as Nones, we ask if there are differences in the opinions in Black respondents and white respondents. Being a None would indicate a set of beliefs on some questions as they are in a single group based at least in part on their view on a religion. But similar views on that one question do not imply similar positions across race on other issues.

There are multiple communities and spaces in the country. Some views will reflect these different spaces. From the survey we see that there are questions in which Black Nones and white Nones have similar beliefs. There are numerous questions in which Blacks Nones and white Nones, on average, hold different beliefs. This could well be related to differences in views within various communities as well as the legacy of different historical circumstances. Spaces for these different communities should be encouraged to flourish.