Why We Need More Black Humanists in Academia

THE NUMBER OF AMERICANS who identify as nonreligious has been steadily growing over the last decade. The Gen Z demographic, in particular, is more willing to identify as humanist and atheist than past generations. Greater numbers of youth are questioning religious teachings and demanding empirical evidence before supporting religious claims.

There is a growing need for young people to be educated about secularism, humanism, and freethought. There is an even bigger need to address secularism within communities of color from an intersectional perspective. Although colleges and universities are critical for exposing young people to humanist world views, secular studies are actually scarce in American higher education.

Indeed, most secular studies courses are housed in theology schools or religion departments that possess only a perfunctory interest in the rise of secularism in the United States and worldwide. In some instances, the subject is studied from an unobjective, unfavorable religious lens through which the rise of secularism, humanism, atheism, and freethought is perceived as a threat to religion and society that needs to be eradicated. This reinforces the negative stereotypes about secularism and humanism in the minds of young people.

At the same time, many of the religious departments that employ intersectional analyses in their academic work, research, and praxis exclude secularist frameworks. This is despite the fact that they can be observed in common theological themes like Black theology, womanist theology, feminist theology, liberation theology, queer theology, disability theology, etc.

Further, the religious and nonreligious academic departments that engage the topic of secularism are dominated by white male tenured professors who are not well versed in the experiences of Black humanists and other communities of color.

The obvious result of this problem is that scholarship, classes, and curricula that reflect the lived experiences, social engagement, politics, and worldviews of humanists of color are scant to nonexistent. Notable exceptions to this are exemplified by the work of Dr. Anthony Pinn at Rice University and Dr. Christopher Cameron at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte.

Regretfully, there are few humanist women of color who are tenured academics and who write about secularism from an intersectional point of view that challenges religious fundamentalism, sexism, white supremacy, classism, and economic injustice in both religious and secular spaces.

The marginalization of Black atheist scholarship is why many American atheists and religious folks are unaware of the existence, history and contributions of Black humanists and feminists—e.g., Frederick Douglass, Fannie Barrier Williams, Hubert Harrison, Zora Neale Hurston, Lorraine Hansberry, Richard Wright, James Baldwin, Nella Larsen, Alice Walker, Octavia Butler, and others—to political and social movements in America.

Consequently, many people wrongly assume that white atheist academics speak for all secular humanists, including humanist people of color. This is an issue that Black humanists confront regularly, especially among religious people who think atheism and humanism belong to white men.

Ideally, there would be multiple secular studies departments in different states conducting in-depth research in diverse communities of color which would help identify the unique trends and issues that are absent from mainstream research about the rise of secularism in the United States.

It is vital to develop intersectional scholarship that frames the ideologies of humanist, secular, queer, and feminist people of color so we can reach more people in these communities—especially younger generations—who are interested in humanism and secularism. Younger generations must have access to knowledge about these Black secular humanist concepts and how they are relevant to their lives. They should know that a rich heritage of Black humanists and secular feminists paved the way for them.

The religious and nonreligious academic departments that engage the topic of secularism are dominated by white male tenured professors who are not well versed in the experience of black humanists and other communities of color.

It is also important that humanist people of color teach, write, and publish research papers and books about their history and present-day activism in order to maintain visibility and remain in the collective memory of the culture around them. History won’t be kind to the people or communities who don’t document and teach their work or ideas. As the novelist Walter Mosley once commented, “If you want to be in the history of the culture, then you have to exist in the fiction. If you don’t exist in the literature, your people don’t exist.”

It is also important that humanist people of color teach, write, and publish research papers and books about their history and present-day activism in order to maintain visibility and remain in the collective memory of the culture around them. History won’t be kind to the people or communities who don’t document and teach their work or ideas. As the novelist Walter Mosley once commented, “If you want to be in the history of the culture, then you have to exist in the fiction. If you don’t exist in the literature, your people don’t exist.”

The only authentic secular studies program in the United States is located at Pitzer College. It was established in 2011 by Phil Zuckerman, atheist author and sociologist of religion. When he first proposed the program, he was met with skepticism. He had to convince the faculty members at the school that secular studies weren’t anti-religion. Thankfully, the program was eventually approved.

In January, educator, activist, and playwright Sikivu Hutchinson will join Pitzer’s Secular Studies program as an adjunct professor. She is one of the most outspoken voices of Black humanist freethought, intersectional feminism, queer activism, and grassroots activism currently in academia. It is a landmark moment because she will be the first Black woman to teach a course on African American Humanism in this one of a kind program.

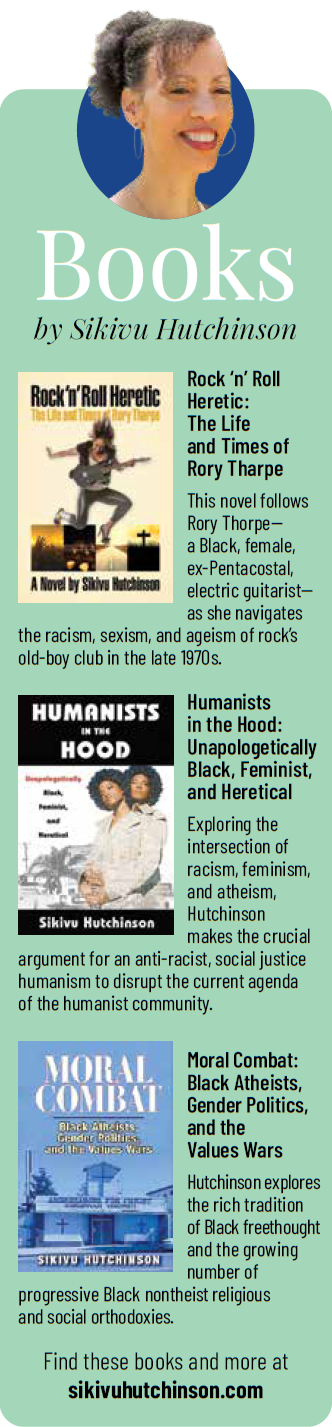

Hutchinson’s most recent novel is Rock ‘n’ Roll Heretic: The Life and Times of Rory Tharpe. She is also the author of books Humanists in the Hood: Unapologetically Black, Feminist, and Heretical (2020), Moral Combat: Black Atheists, Gender Politics, and the Values Wars (2011), and Imagining Transit: Race, Gender, and Transportation Politics in Los Angeles (2003) as well as the play White Nights, Black Paradise (2015). Moral Combat was the first book on atheism to be published by an African-American woman. She is the founder of Black Skeptics Los Angeles, a group committed to promoting the work of black skeptics, freethinkers, atheists, agnostics, and secular humanists through social justice education initiatives. In 2020 she was a recipient of the Harvard Humanist of the Year award. She was also named Woman of the Year by Secular Woman in 2013, received Foundation Beyond Belief’s Humanist Innovator award in 2015, and the Secular Student Alliance’s Backbone Award in 2016.

The “African American Humanism” course will focus on how Black humanist traditions have influenced Black liberation, resistance, art, and intellectualism.

According to Hutchinson,

Drawing from my book Humanists in the Hood: Unapologetically Black, Feminist, and Heretical, the impetus for this course is the virtual absence of Black feminist humanist “praxis-based” scholarship in the small, white-dominated field of Secular Studies. Unfortunately, the majority of courses on secularism are situated in religious studies departments that do not necessarily reflect the racial, ethnic, and cultural diversity of secular humanist culture and social history. Moreover, Black women comprise only two percent of tenured professors in American colleges and universities—further underscoring how racist-sexist faculty hires translate into negligible representation for Black students in academe. With this course, I hope to not only expand student perspectives on the trajectory of American humanism, but inspire new generations of scholars to explore how contemporary Black humanism also disrupts narratives about American exceptionalism and the American dream—especially as anti-blackness escalates in K-12 and higher education. How, for example, do we begin to look at such dynamics as mass incarceration, the normalized misogynoir Black girls experience, and Black queer resistance through a Black humanist lens? What are the lived experiences of Black humanists and secularists in apartheid urban America in the pandemic age? What role can humanism play in culturally responsive education? These are all themes that shape my life’s work which I will be infusing into this course.

As Hutchinson notes, Black humanists have historically grounded their beliefs in an anti-racist social justice critique that was distinct from that of European American secular humanists. For generations, African American secular humanist inquiry has provided Black thinkers, activists, and educators with a platform to explore questions of race, ethics, democracy, gender, sexuality, white supremacy, and capitalism, as well as global citizenship, American national identity, utopia and dystopia. The course will foreground how these traditions shaped Black liberation, resistance, intellectualism, and creativity. It will explore major currents in African American Humanism from slavery-era critiques of organized religion to contemporary twenty first century secular humanist, freethought and atheist activism, scholarship, art and social media among educators, writers, bloggers, and organizations who are challenging the dominance of religious faith in communities of color.

The marginalization of Black atheist scholarship is why many American atheists and religious folks are unaware of the existence, history and contributions of Black humanists and feminists to political and social movements in America.

A major part of the course will be devoted to the feminist intersectional voices and perspectives of Black secular women and Black LGBTQI+ secularists. For Black women and women of color in general, the absence of alternative secular spaces and sites of political agency in communities of color is directly related to intersecting race, class, income, wealth, and geographic disparities. Racist/sexist stigmas demonizing the morality and sexuality of women of color in traditionally religious cultures have also been major barriers. In addition to featuring the work of prominent Black humanist figures like Alice Walker, Nella Larsen, Zora Neale Hurston, Richard Wright, Mandisa Thomas, Pinn, and Cameron, the course will also feature Black feminist-womanist writers such as Toni Morrison, Suzan Lori Parks, Octavia Butler, NK Jemison and Dorothy Roberts, as well as Maureen Mahon’s humanist-themed work on Black women in rock music.

A major part of the course will be devoted to the feminist intersectional voices and perspectives of Black secular women and Black LGBTQI+ secularists. For Black women and women of color in general, the absence of alternative secular spaces and sites of political agency in communities of color is directly related to intersecting race, class, income, wealth, and geographic disparities. Racist/sexist stigmas demonizing the morality and sexuality of women of color in traditionally religious cultures have also been major barriers. In addition to featuring the work of prominent Black humanist figures like Alice Walker, Nella Larsen, Zora Neale Hurston, Richard Wright, Mandisa Thomas, Pinn, and Cameron, the course will also feature Black feminist-womanist writers such as Toni Morrison, Suzan Lori Parks, Octavia Butler, NK Jemison and Dorothy Roberts, as well as Maureen Mahon’s humanist-themed work on Black women in rock music.

For Zuckerman, the course couldn’t be more timely. He noted that:

It is really thrilling to have Professor Hutchinson offering “African American Humanism” within our Secular Studies program here at Pitzer College. I’ve been a fan of Sikivu for a long time; I’ve assigned her writings to my students and have had her give guest lectures here on campus. She is one of the sharpest, most insightful minds out there. And she pushes and challenges those of us within the secular humanist community to be more inclusive, more intersectional, and more attentive to matters of racism, sexism, and other issues of inequity and injustice in ways that are sorely needed. More and more people of color are embracing secular humanism, and Sikivu has been a real beacon for those on that path. Her class will certainly broaden students’ understandings of both secularity and race. The value here is enormous. Already I’ve heard from so many students who are excited to take the class.

This is a positive step for humanist scholarship. Hutchinson’s new role is paving the way for more Black humanist feminists who will engage with secularism, humanism, and freethought in academia. But it isn’t enough to celebrate. The secular community must make more of an effort to promote humanists of color who are tearing down the exclusive and privileged walls between the ivory tower and the classroom, community center, workplace, dinner table, and protest grounds. Hutchinson’s new position in academia and the classroom is a beacon of light.