The Hidden Hues of Humanism

For years it has been lamented that humanist groups and events lack adequate participation by racial minorities. “Our philosophy is inclusive,” goes the refrain. “Our doors are open. Anyone can come.” Nonetheless, the usual overwhelmingly white demographic remains substantially unchanged.

We imagine we understand why. African-American and Hispanic communities are without freethought traditions, we argue, and longstanding religious orientations are built into their cultures. Therefore it’s up to us to bring humanism to them and hopefully overcome a longstanding bias against it. But, it turns out, that would be like bringing cheese to Wisconsin.

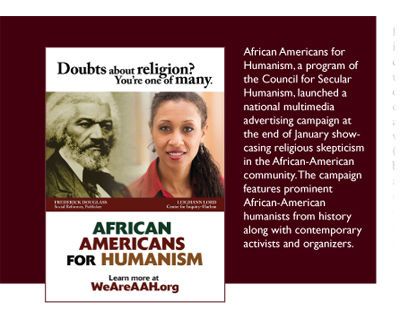

There is already a robust freethought tradition in the black community, for example. We can go back at least as far as abolitionist Frederick Douglass. NAACP cofounder W. E. B. Du Bois is another prominent example. During the Civil Rights movement of the 1940s through the ’60s the leader of its well-established secular wing was journalist and union organizer Asa Philip Randolph. He organized the 1963 March on Washington at which Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his famous “I Have a Dream” speech. Randolph was later recognized in 1970 by the American Humanist Association with its Humanist of the Year Award. Another such activist was Freedom Ride organizer James L. Farmer Jr., founder of the Congress of Racial Equality and the 1976 AHA Humanist Pioneer. Beyond social justice advocacy, we find the arts overflowing with prominent black freethinkers. During the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s through the ’40s, writers such as Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, Nella Larson, and Richard Wright could be counted among them. Emerging later were jazz saxophonist and composer Charlie “Bird” Parker, author James Baldwin, and novelist Alice Walker, who was named the 1997 Humanist of the Year.

There is already a robust freethought tradition in the black community, for example. We can go back at least as far as abolitionist Frederick Douglass. NAACP cofounder W. E. B. Du Bois is another prominent example. During the Civil Rights movement of the 1940s through the ’60s the leader of its well-established secular wing was journalist and union organizer Asa Philip Randolph. He organized the 1963 March on Washington at which Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his famous “I Have a Dream” speech. Randolph was later recognized in 1970 by the American Humanist Association with its Humanist of the Year Award. Another such activist was Freedom Ride organizer James L. Farmer Jr., founder of the Congress of Racial Equality and the 1976 AHA Humanist Pioneer. Beyond social justice advocacy, we find the arts overflowing with prominent black freethinkers. During the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s through the ’40s, writers such as Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, Nella Larson, and Richard Wright could be counted among them. Emerging later were jazz saxophonist and composer Charlie “Bird” Parker, author James Baldwin, and novelist Alice Walker, who was named the 1997 Humanist of the Year.

Among Hispanics, far and away the most famous freethinker is Simón Bolívar, the great liberator of South America. Later, the humanistic Positivist Church had a strong social influence across the continent and left its mark on the Brazilian flag with the slogan, “Order and Progress.” Nonetheless, the Roman Catholic Church remains a ubiquitous presence in Hispanic communities, leading nontheistic Mexican novelist Carlos Fuentes to note, “In Latin America, even atheists are Catholics.”

Still, the question remains: Why are minority communities so lacking in an overt humanist presence today? And what can be done about it? Norm Allen Jr., founder of African Americans for Humanism, has struggled with these questions. Writing in a forthcoming special issue of Essays in the Philosophy of Humanism, he acknowledges his inability to answer. “For twenty-one years I had been the only full-time African American humanist activist traveling the world to promote secular humanism. Yet I still cannot unravel the mystery.”

Still, the question remains: Why are minority communities so lacking in an overt humanist presence today? And what can be done about it? Norm Allen Jr., founder of African Americans for Humanism, has struggled with these questions. Writing in a forthcoming special issue of Essays in the Philosophy of Humanism, he acknowledges his inability to answer. “For twenty-one years I had been the only full-time African American humanist activist traveling the world to promote secular humanism. Yet I still cannot unravel the mystery.”

But over the past year, likely answers have begun to emerge, provided courtesy of a new breed of minority humanists. Before we can understand their response, however, we need to better understand the present situation and how it came to be that way.

According to the 2009 Pew Forum study, “A Religious Portrait of African Americans,” 87 percent of those in the U.S. black population describe themselves as “religious” and 88 percent say they are “absolutely certain God exists.” Latinos have had similarly high figures in Pew surveys. Also in 2009, the Barna Group reported that 92 percent of African Americans identified as Christian, were more likely than whites to regard themselves as “born again,” and had a faith that is “moving in a direction that is more aligned with conservative biblical teachings.” Similar findings were reported for Hispanics. “Born agains” in that population “were more likely than all born-again Americans to contend that they have been greatly transformed by their faith.”

These realities make overt atheism largely taboo in such communities. Ethelbert Haskins has identified a contributing factor. Being an African American who was a leader in both the Civil Rights and humanist movements of earlier years, he notes that there are indeed many nontheistic people of color, but they don’t feel comfortable coming out as nonbelievers “until grandma dies.” They fear their irreligion would prove painful for older relatives and thereby estrange them from the family. Which means that black atheists and humanists are often fairly old themselves before the time is right, and by then it seems unnecessary to join a group, living comfortably as they have for so long in the closet.

If this seems like a weak point, because the same thing can be said for many whites who come from traditionally religious families, one needs to understand that the situation is statistically less frequent for the latter. After all, as the most populous and dominant group in the United States and Canada, whites enjoy greater latitude. Their raw numbers, varied cultural origins, and social mobility result in a wider range of acceptable religious (and hence nonreligious) choices. This makes white culture broad rather than insular, permissive rather than restricted. And unlike minorities living in oppressed neighborhoods, or working hard to gain middle-class acceptance, whites generally lack the bunker mentality or out-group status that tends to promote cultural conformity and identity politics.

Feminist/atheist activist and author Sikivu Hutchinson dives further into this in her 2011 book, Moral Combat: Black Atheists, Gender Politics, and the Values Wars.

The legacy of Jim Crow and de facto segregation has limited black residential mobility, creating socioeconomic conditions in which blacks of all classes, incomes, and education levels live in close proximity to each other. Hence, African Americans remain the single most segregated racial group in the United States.

This leads to an insular culture where Christian verbal expression flourishes in tandem with the dominance of churches as social institutions. In this context, certain humanist values are perceived as out of step with black experience. Hutchinson adds that “in communities plagued with double-digit unemployment and cultural devaluation, self-sufficiency and ultimate human agency may be perceived as demoralizing if not dangerously radical.” So a philosophy of dependency promoted by Christianity takes precedence. In such an environment, a concept of black “essentialism” or identity politics has developed that explicitly includes opposition to secularism. In her 1990 essay, “Postmodern Blackness,” feminist and social activist bell hooks has objected to this trend.

We have too long had imposed upon us, both from the outside and the inside, a narrow constricting notion of blackness. . . . This discourse created the idea of the “primitive” and promoted the notion of an “authentic” experience, seeing as “natural” those expressions of black life which conformed to a pre-existing pattern or stereotype.

Hutchinson shows just how far this has gone: “While there is tolerance for the very public bigotry of the Black Israelites, African Americans collectively view atheism and atheists as distasteful… [and] have some of the most negative views of atheists among all groups.” Why? Because, says Hutchinson, in a nation that remains racist, “the otherness and deviance associated with atheism is at odds with the elusive quest for assimilation [by racial minorities].” As a result, black atheists are closeted and invisible and represent only 1 percent of the black population.

This is why it has proved so difficult for many to come out as atheist, agnostic, or humanist. The New York Times reported on their struggles in “The Unbelievers” by Emily Brennan, published November 25, 2011, noting that many have turned to interactive websites and online social media: “Feeling isolated from religious friends and families and excluded from what it means to be African American, people turn to these sites to seek out advice and understanding.”

A different situation, however, seems to be the case for Hispanic immigrants. In a 2007 New York Times article, Laurie Goodstein found that “increasing percentages of Hispanics are abandoning church, suggesting to researchers that along with assimilation comes a measure of secularization.” But, again, because the Roman Catholic Church remains a strong presence in Hispanic neighborhoods and a significant part of Hispanic identity, overt expressions of irreligion or nontheism remain frowned upon.

It is for these reasons that the simple notion of humanism’s doors being open to all comers can be seen as naive. Communities of color really are quite different places from white communities. And people of color who come to nontheistic conclusions really are in a significantly different position from whites who have done the same thing.

But there’s more. The actual needs of minority humanists differ just as significantly. And this means that mainstream humanist groups, in addressing the interests of the demographic they currently serve, can’t help but miss the mark for minority populations. Why, for example, would someone living in the inner city—dealing with the hard issues of economic survival, epidemics of drug abuse and AIDS, violent crime, urban blight, and other social problems—find it useful or even interesting to work her or his way through a cumbersome public transit system (designed to keep those from minority and poor neighborhoods balkanized) to reach the middle-class white suburbs and attend a humanist lecture or discussion about some abstract philosophical, scientific, or cultural matter or engage in social action on a mere symbolic issue like ceremonial deism? After only a moment’s thought, the utter irrelevancy of many humanist gatherings to minority concerns becomes staggering.

And when it comes to abstractions, whites like to talk about the European Enlightenment as if nothing bad could ever legitimately be said about it. But Enlightenment rationalism was experienced differently by those of African extraction. Knowledgeable people of color are acutely aware that, despite the universalized language of this tradition’s thinkers and activists, non-whites really weren’t included among the “all men” who were “created equal” in the estimation of America’s founders. It would take generations to include the unpropertied, women, and non-whites among those recognized as fully human and therefore entitled to full rights and citizenship.

And when it comes to abstractions, whites like to talk about the European Enlightenment as if nothing bad could ever legitimately be said about it. But Enlightenment rationalism was experienced differently by those of African extraction. Knowledgeable people of color are acutely aware that, despite the universalized language of this tradition’s thinkers and activists, non-whites really weren’t included among the “all men” who were “created equal” in the estimation of America’s founders. It would take generations to include the unpropertied, women, and non-whites among those recognized as fully human and therefore entitled to full rights and citizenship.

Joseph Graves, in The Emperor’s New Clothes: Biological Theories of Race at the Millennium, states: “Eighteenth-century ‘Enlightenment’ scholars never doubted that God and science declared the existence of races and that there should be hierarchical relations between them.” For more than two centuries religion and science were in total agreement about racial difference, even when social opinion differed as to how best to respond to it. This is why both black slavery and programs to ship emancipated slaves “back to Africa” (as President James Monroe instituted) were not mere aberrations in an otherwise noble and universal Age of Reason philosophy. They were part and parcel of it.

After the abolition of slavery in the United States, blacks continued to be regarded as inferior, even by many progressive whites. Hutchinson draws attention to atheist women’s suffragist Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who took issue with the idea of giving black men the vote before it was conferred upon white women, declaring in an 1869 speech that if white women found it hard to live under the rule “of their own Saxon fathers, the best orders of manhood,” how unendurable might it become “when all the lower orders of foreigners crowding our shores legislate for them.” She called on her audience to think of “Patrick and Sambo and Hans and Yung Tung who do not know the difference between a monarchy and a republic.” How unfit they were for the vote, she thought, especially ahead of American women of Anglo-Saxon descent.

Facing this type of opinion, American blacks rejected as exemplars the slave-owning freethinkers of the Enlightenment in favor of a biblical Jesus who spoke to the humanity of the most dispossessed elements of society, and of a loving God who would dole out just deserts with an even hand in the next life. Moreover, as Hutchinson notes, in terms of gaining social acceptance among whites, Christianity “gave African slaves purchase on being human, on being American, and on being moral.” Blacks adopting Christianity seemed to force whites to recognize them as fellow believers and hence equals. This was therefore “the price of the ticket” to eventual citizenship and acceptance. Which explains the embarrassing adoption of “the god of our kidnappers, murderers, slave masters, and oppressors,” as blogger Wrath James White put it.

It isn’t enough, then, for mainstream humanists to point out this contradiction. Hutchinson writes: “Many humanists and atheists of color… chafe at white atheists’ often paternalistic and ahistorical criticism of the role religion has played in African-American, Latino, and Native-American cultures.” Whites need especially to understand the importance religion has had for African-American identity throughout the struggle for civil rights, civil liberties, social justice, and equal recognition. And they need to become more aware of the positive social benefits churches have conferred upon minorities. “A balm for suffering, a source of atonement, and a nexus for kinship and community, organized religion serves multiple functions in African American communities,” Hutchinson contends.

That suffering experienced by oppressed groups is the initial impetus that creates a need for religion and religious institutions. Churches then become central to the degree that they provide necessary services, social and professional networking, and a base for socio-political activists and candidates. By this process, the communal dimension of faith becomes the glue that holds the community together.

Moreover, explains Hutchinson, “For communities of color, the lifeblood of organized religion is economic injustice.” Those unaware of their privilege don’t suffer economic injustice, so nontheism comes relatively easy. But in communities of color, only the churches redress some of the imbalance. This means that, in order to be relevant to the oppressed, humanist groups must take on economic injustice and offer a viable alternative to the services provided by churches.

Until they do, there will always be a high social cost for those who publicly abandon the faith. Such an act in the black community amounts to nothing less than race treason, especially given the significance of the black church during the Civil Rights era.

Nonetheless, something has changed. And therefore humanists of color are at long last starting to emerge. Hutchinson maintains that “the social justice compass” of the dominant black churches “has been broken by consumerism, institutional sexism, and faith-based witch hunts of gays and lesbians,” making their moral capital increasingly dubious. A blog post on January 17 of this year at the WTLC 106.7 FM (Indianapolis) website seemed to agree: “Many black churches preach abstinence over safety and refuse to endorse the use of contraceptives, while supporting conservatives on policies such as the disintegration of Planned Parenthood, which provides life-saving and preventative treatment for people of color.”

Beyond this, urban Christianity has abandoned its social justice leadership and begun more and more to prey on the communities it used to serve. Black megachurches have created lavish lifestyles for their charismatic leaders, complete with sex scandals. And these leaders are always male, benefiting from the traditional patriarchy that continues to dominate the black community, much to the detriment of struggles for the rights of women and gays. This adds up to these churches acting in clear betrayal of the interests of the black community.

So it is in this context, the context of social justice, that traditional faith needs to be critiqued in minority communities. And this need has generated a perceived urgency on the part of today’s black atheists and humanists. Absurdities of theological doctrine, revealing discoveries of biblical scholarship, and the fact of scriptural contradictions are considered irrelevant here. But the latter are what mainstream humanist groups tend to focus on when they discuss religion. Hutchinson complains, “There is little analysis of the relationship between economic disenfranchisement, race, gender, and religiosity in New Atheist or secular humanist critiques of organized religion.”

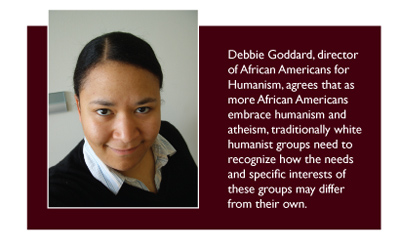

And this may answer the question as to why humanists in the United States and Canada are mostly white. Their humanism fails to notice white privilege, fails to see that the needs their philosophy addresses are particular, not universal. And operating from such an orientation, the dominant humanist organizations, national and local, go on to view the concerns specific to racial minorities as narrow or specialized—hence outside the broad philosophical generalities they prefer to address.

This marginalizing of minority concerns, Hutchinson argues, undermines “the possibility of any sustainable cross-racial alliances around humanist issues.” Meaning that, “in the absence of an explicitly anti-racist, anti-sexist, anti-heterosexist, and anti-imperialist critical consciousness there will continue to be a major divide between white atheist discourse and the lived experiences of humanists of color.” One might take the defiant expression, “No justice, no peace” and rework it to say, “No justice, no African-American humanism.”

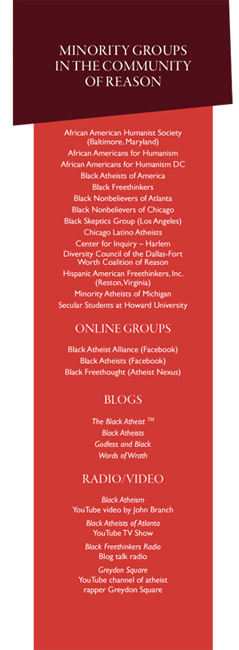

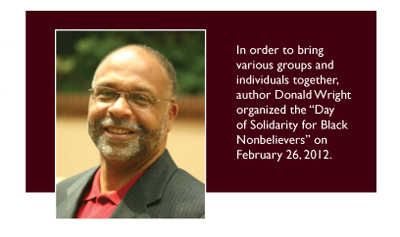

Clearly, Hutchinson’s call is a radical one, more likely to be met by humanists of color themselves. And this is exactly what is beginning to happen. Under her leadership and that of others, new minority atheist and humanist groups have emerged, such as Black Atheists of America and Black Freethinkers. And to bring the various groups and individuals together in this struggle, Donald Wright, author of The Only Prayer I’ll Ever Pray: Let My People Go, organized a Day of Solidarity for Black Non-believers on February 26, 2012. The goal, says Wright, is to make it an annual celebration on the fourth Sunday in February to “encourage community activism” as well as “promote fellowship, share experiences, meet new nonbelievers, and discuss the lives of black nonbelievers that our typical history books omit.”

Clearly, Hutchinson’s call is a radical one, more likely to be met by humanists of color themselves. And this is exactly what is beginning to happen. Under her leadership and that of others, new minority atheist and humanist groups have emerged, such as Black Atheists of America and Black Freethinkers. And to bring the various groups and individuals together in this struggle, Donald Wright, author of The Only Prayer I’ll Ever Pray: Let My People Go, organized a Day of Solidarity for Black Non-believers on February 26, 2012. The goal, says Wright, is to make it an annual celebration on the fourth Sunday in February to “encourage community activism” as well as “promote fellowship, share experiences, meet new nonbelievers, and discuss the lives of black nonbelievers that our typical history books omit.”

Meanwhile, groups of Hispanic atheists are also emerging. Jose Alvarado of Chicago Latino Atheists has set up his group to “discuss contemporary issues regarding Hispanics/Latinos and the predominance of religion in our culture” and “make atheists more visible in our local communities by promoting education, community service, secular religious education, and upholding the separation of church and state.”

Such changes in minority humanist advocacy have grown out of a recognition that one size doesn’t fit all. Since we don’t live in a post-racial society, since white privilege continues to exist, and since the predominant form of humanism doesn’t have the “unraced” status its proponents seem to imply for it, then organizations specifically focused on the needs of racial and ethnic minorities have become a necessity.

May they grow and thrive.