What Humanists Can Learn from the Occupy Wall Street Protests

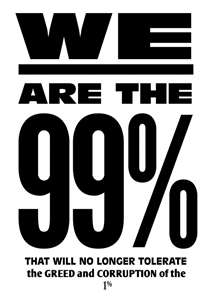

Occupy Wall Street is now in its fourth week, and the ongoing protests against corporate power that began on September 17 have now seen thousands of Americans of all backgrounds take to the streets of New York. The Occupy Wall Street protest has also inspired hundreds of solidarity protests across the U.S. with three distinct Occupy protests here in Washington DC alone. It remains to be seen what long-term effects the “Occupy movement” will have on American electoral politics, but I firmly believe that they have already ushered in a paradigm shift in how Americans of all backgrounds conduct and understand grassroots political organizing and non-violent civil disobedience.

While humanists agree that our focus should be on compassion for others, we don’t often agree on the best economic strategy for doing so, and the American Humanist Association doesn’t generally take sides on divisive economic choices. While progressive on most issues, humanists identify themselves as being all across the political spectrum and beyond it.

So the question for us is not whether or not to support the Occupy Wall Street protest itself, but rather: what can we humanists learn from the energy of this and related protests in our ongoing work to build a more ethical society and a more democratic government that is responsive to the needs and rights of human beings? As AHA president Dave Niose wrote in an article for the Humanist earlier this year, “As humanists survey the landscape and consider issues of economic injustice and participatory democracy, the issue of corporate power and influence should stand out as key. This is a definable problem that has direct effects transcending the economy, going right to the heart of our democracy and our culture.”

While I was personally unable to travel to New York on September 17 to be present at the start of Occupy Wall Street, I joined virtually with the initial Occupy Wall Street protest via Twitter updates. Social media has been a powerful tool in the development of this protest as thousands of activists provided live commentary from the ground. While watching live streaming coverage of the Occupy Wall Street march on September 24–the day of the first infamous pepper-spray incident—I witnessed alongside 4,000 other viewers as discussion moderators worked tirelessly to keep the protests focused on peaceful change even in the face of police violence. And on October 6 I joined the Occupy DC protest and watched as hundreds of peace activists at Freedom Plaza joined online with Afghani peace activists in challenging the U.S. defense industry and their complicity in the now ten-year-long war in Afghanistan.

One of the most crucial lessons I have learned from my involvement in the Occupy movement is how important it is that no one voice can or should try to speak for everyone involved. Occupy Wall Street is purposely a leaderless protest, and while initially a call to action was first made asking protesters to articulate “one demand,” the protests took on a life of their own with a multitude of demands and messages, many of which are to be found in this statement issued by the NYC General Assembly on September 29. I find the often-made characterization of Occupy Wall Street as “the Democrats’ answer to the Tea Party” both erroneous and misleading—while current and past experience within the Republican Party is a widely-shared characteristic of Tea Party leadership, organizers of Occupy Wall Street come from diverse party affiliations (or none), and primarily share past experience in non-violent grassroots organizing, whether that be the peace movement, the labor movement, the environmentalist movement, or the civil rights movement. And many of the protesters are humanists, atheists, and secular Americans, and they are asking for separation of corporation and state, separation of oil and state, and yes, separation of church and state.

It’s also worth noting that the organizational structure of Occupy Wall Street is such so that all decisions are made through a general assembly—an open, participatory and horizontally organized process to develop an autonomous collective force in response to the crises of our times. It is an exercise in participatory democracy that in-and-of-itself challenges the hierarchical organizational structure of the powers they are critiquing.

Like all great social movements, Occupy Wall Street and related protests were inspired by other movements, especially the Arab Awakening, but it has turned that energy into something distinctly new. Humanists should try to learn from what is happening on the ground by protesters all around the nation by engaging in online discussions and learning more about what the general assemblies are accomplishing.

If you are following the Occupy Wall Street protests, I encourage you to share what you have learned—and what you think humanists can learn—in the comments below.