Selective Sympathy: Why the World Cared About Brussels (But Ignored Others)

We’re still in mourning. And at the same time, we’re in disbelief. We can’t help but experience the hair-raising primal fear that floods our being, plunging us into a heightened sense of paranoia and vulnerability. We can taste the “fed up” sticking to the back of our throats as we swallow our indignation and breathe out exasperation. We think, “Not again.” We are again wary, but we are also weary.

These are the typical reactions to acts of terror.

I think of the children, both those who have perished and those who lost parents or siblings in the wake of terrorism. I think of all the victims: what their last meal was, what their last thoughts may have been, what plans they had for that day.

Yet this anguish and devastation I describe isn’t your sorrow. It isn’t what the vast majority have been following in around-the-clock news coverage. Yes, I’m talking about recent terrorist attacks, but because what I’m referring to didn’t occur on US or European soil, Western media has largely downplayed its significance.

Why?

It’s all about narratives. I often quote American academic Robert McKee, who once said, “Storytelling is the most powerful way to put ideas into the world today.” Whether we want to acknowledge it or not, news media is a form of propaganda. When it comes to the Western world, major news outlets are founded on white supremacist ideology and diligently nourish the concerns of a white-oriented culture.

This isn’t to say “all white people hate people of color” or that “all whites” are aligned with the likes of skinheads and those who gallivant in white hoods screaming “White Power!” No. What it means is that there is oftentimes a surplus of value assigned to certain lives and circumstances while a distinct deficit of regard is extended to others. The demarcation between which response a disaster receives is usually dependent on its relatability to whiteness.

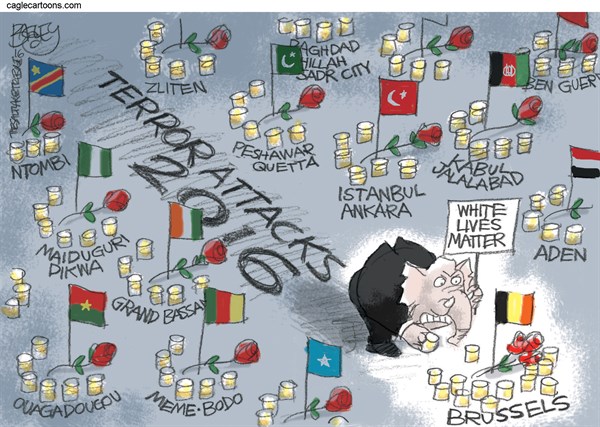

Cartoon by Pat Bagley, Salt Lake Tribune

When terrorist attacks are perpetrated in countries like France or more recently Belgium, news reports are intensified and abundant. Political officials—including our president—are compelled to publicly address the situation. Counterterrorist experts are interviewed and dispense commentary from their informed perspectives. Facebook enables flag filters on profile pictures or the like to exhibit solidarity. Many tap into a concealed reserve of empathy that always seems to manifest whenever white lives are lost.

As a collective we become engrossed, eulogize the fallen, and insert ourselves into the condition of those experiencing the tragedy firsthand. In the midst of consoling white-centered heartache and calamity, a now common refrain is recited as a means to memorialize the victims of wrongdoing while also demonstrating unity against the crick of terror—Je suis, French for “I am.” We were Charlie, then we were Paris, and now the nation has determined that “we” are also Brussels.

And while violence in Europe results in a torrent of compassion and outcry across our mainstream media streams, it’s impossible not to recognize who doesn’t receive the same attention and compassion. Nine days before the bombings in Brussels, Ankara—the capital of Turkey—was hit with a terrorist bombing of their own that killed thirty-seven people and injured hundreds. The month prior, thirty people were slain and sixty wounded in Ankara. The Kurdistan Freedom Falcons (TAK), a militant group that terrorizes the eastern quadrant of Turkey as they seek an independent Kurdish state, claimed responsibility for both attacks. Neither explicit act of terrorism generated a fraction of the public attention or mass media garnered by Brussels.

In late January, Boko Haram murdered eighty-six people—including children, burned alive—in Dalori, Nigeria. On March 13, the same day as the second Ankara incident, a mass murder perpetrated by Al-Qaeda at a beach resort in Grand Bassam, Ivory Coast, left eighteen dead and thirty-three wounded. Three days later on March 16, two women suicide bombers attacked a mosque in northeastern Nigeria (Maiduguri), killing twenty-four and injuring eighteen. These real-life horror stories neither received an international media blitz nor widespread displays of support.

This isn’t all, however—what’s evident is that our culture’s “selective sympathy” that marginalizes some incidents while highlighting others is based on its proximity to whiteness.

Whiteness isn’t merely a reference to skin color. Whiteness describes a socially and politically constructed concept. It’s a relational description that only exists in opposition to other categories in the racial hierarchy with a European origin used to justify slavery. Whiteness defines itself by demarcating a separation from “others.” Whiteness is both a systemic and systematic ideology based upon beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors that results in unequal distribution of power and privilege that accords a higher regard for the intellectual, behavioral, and inherent value of those defined as “white.”

In addition to whiteness, we must also consider political rhetoric.

Post-9/11, a popular tool of political demagoguery has been to appeal to the fear of the “othered” enemy—Islamic extremism. In recent years, the media and political arena have debited the embodiment of that anxiety from Al-Qaeda and transferred it into the vessel of the latest imagined prime evil: ISIS. By virtue of the angst lodged into the US social consciousness fifteen years ago, terms like “terror” and “terrorism” have become forged with the narrative of whiteness and narrowly redefined to chiefly refer to “Islamic radicalism that threatens or harms white lives.”

The hundreds of brown and black lives lost in Ankara, Grand Bassam, Maiduguri, and Dalori received virtually no “gnashing of teeth” from the West because these episodes fall outside this warped lens. There were two bombings in Beirut that murdered forty-three and injured hundreds a day before the Paris bombings last year. Both incidents were carried out by ISIS. One of these tragedies involved the loss of white lives and received a deluge of condolences and solidarity. The other, perpetrated against Shia Muslims, received a global cold shoulder.

In January of 2015, during the same time of the Charlie Hebdo attacks, Boko Haram carried out a massacre in Baga, Nigeria, that claimed the lives of hundreds over the course of five days. One of these tragedies involved the loss of white lives and received a worldwide saturation of attention and sympathy. The other, perpetrated by a terrorist network statistically more deadly than ISIS against African citizens and African military personnel, was the recipient of stark unconcern.

Today, one day after an Easter bombing in Pakistan killed at least 70 and injured more than 300, the trend of media (and social media) bias and diminished distress over terrorism that doesn’t impact white lives still holds true.

Educator, social critic, and activist Zellie Thomas summed up this tendency with the following statements:

We are all France. We are all Belgium. We are never Nigeria. Never Palestine or Lebanon. Ivory Coast or Burkina Faso.

— zellie (@zellieimani) March 22, 2016

Does the flag filter for tragedies only come in European countries?

— zellie (@zellieimani) March 22, 2016

Our nation’s preoccupation with terrorism is largely proportional to the way threats or events relate to implied beliefs that, either consciously or subconsciously, hinge on the superiority of white lives and how this prerequisite intersects with Islamic extremism, the designated foe. Thus, there are no je suis moments for lives, regions, or circumstances that don’t fit within this sociopolitical framework.

The fact that ISIS murders more Muslims than any other group is omitted from the narrative many media sources relay in an attempt to nurture the “Muslims are against us” mindset. Despite only a fraction of Muslims worldwide associating with radicalized forms of Islam, this doesn’t deter the splash damage of this narrative breeding cultural antipathy for anyone perceived to be Muslim, including Sikhs.

Humanism is about the inherent and equal significance of all human life. As humanists, let’s take the time to recognize, contemplate, and pushback against this inequitable status quo that continues to be uncritically observed. The value of human life shouldn’t depend on racial affiliation and political agenda.