What We’re Learning from the Pledge Kids Critical thinking is often met with hostility in American schools

The American Humanist Association’s Don’t Say the Pledge campaign, which encourages a boycott of the Pledge of Allegiance until the “under God” wording is removed, has revealed a troubling phenomenon in American public schools, a common occurrence that would seem to reflect a dangerous tendency in the culture at-large.

As part of the campaign, the AHA asked kids to provide feedback about their experiences in sitting out the pledge exercise in their schools. (The constitutional right to do so has been well established since a 1943 Supreme Court decision.) What we’ve discovered is that attempts to opt out of the pledge are frequently met with great hostility from teachers who take offense to nonparticipation.

This would be bad enough, but it gets worse. Not only are kids too often berated for simply choosing to not pledge allegiance, but we are also finding that the badgering almost always follows the same script: In almost every disapproving exchange between teachers and students reported to us, the teacher accuses the nonparticipating student of insulting America’s troops. Thus, the student is suddenly cast, in front of classmates, as unsupportive of America’s fighting men and women.

Thankfully, not every child who opts out reports being confronted by his or her teacher, but far too many are, and it is revealing that almost every child who is harassed reports being accused of not supporting the troops. This is the go-to argument of teachers who admonish nonparticipants, and its ramifications are distressing. Although patriotism and militarism have long been close relatives, we find that today’s America has become a nation seemingly unable to distinguish the two. The simple choice of a child to sit out the pledge is now widely criticized with not-so-subtle allusions to military disloyalty–not just by ignorant folk, but by educated teachers. One could reasonably ask what this says about contemporary American society and where it is heading.

Bear in mind that America has also become a population convinced of its own exceptionalism at levels that border on overcharged nationalism. High-level politicians are now required to mention that we are “the greatest nation on earth,” and any suggestion of national humility is interpreted as weakness. Never mind that our rates of violence and rates of teen pregnancy are both embarrassingly high when compared to other developed countries, and never mind that our population rejects evolution and other scientific facts at rates far exceeding the rest of the developed world—we nevertheless see ourselves as vastly superior. This chasm between self-image and reality is stupefying.

Carrying these misperceptions, we also far outspend the rest of the world militarily, and it is this militarism that has now become synonymous with patriotism. Most students sitting out the pledge are no doubt doing so for admirable reasons—they have thought seriously about what the pledge means and, after careful consideration, made a conscious decision to not participate. But within the very institutions that should be nurturing such independent thinking, we are instead seeing it attacked. Educational stewards are pointing McCarthyist fingers at thoughtful children and making the pathetic claim that a teenager failing to pledge allegiance is somehow slapping an American soldier in the face.

That educators in America are making such allegations—and not rarely, but often—does not bode well for the nation. As I’ve written elsewhere, there are numerous reasons for sitting out the pledge, and it is extremely narrow-minded to equate pledge nonparticipation with national disloyalty. No other developed democracy expects its youth to take a daily pledge of national loyalty, but America now not only expects it, we will lash out at those who refuse by suggesting they are “insulting the troops.”

Note that, despite its militaristic overtones, there is nothing in the chiding of nonparticipating students to suggest that the teachers involved have any interest in a rational discussion of American militarism. No student has reported that any pledge-obsessed teacher has suggested, for example, that the best way to support our men and women in uniform might be to keep more of them stateside. This would apparently run contrary to the conformity that these teachers expect of their young patriots.

Indeed, dare we even suggest that these teachers spend less time glorifying the flag and the militarism that they tie so closely to it, and more discussing the underlying causes of the conflicts that seem to necessitate American military adventurism? How did it come to be, for example, that Islamic fundamentalism—the phenomenon that we always seem to be fighting—has ignited all across the Middle East and elsewhere? Could it have causal roots that go back to Western colonialism and oil interests?

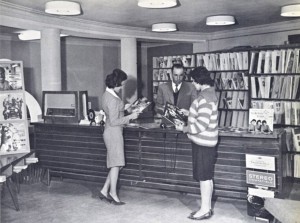

Women in Afghanistan today wear burqas and are denied formal education, but for much of the twentieth century the country reflected much more liberal, modern standards, as is seen in this 1953 photo of a Kabul record store. Fundamentalist Islam now dominates the country in part due to American support of the fundamentalist Muslims opposed to the Soviet Union in the late 1970s and 1980s. Under the “patriotic” view of history proposed by some conservatives, such unpleasant details of American policy might be excludes from curricula. Photo credit: Foreign Policy.

Teachers and students truly interested in supporting American troops might engage in some serious intellectual inquiry on such issues. For example, we can all agree that the theocracy in Iran is ugly, but what’s the story behind the American-backed coup that ousted a democratically elected secular leader of the country back in the 1950s? And Afghan society surely is oppressive these days as well, especially for women and girls, but why is it that Afghanistan was relatively modern and liberal half a century ago, before America helped arm radical Islamists? And while we’re at it, doesn’t much Islamic fundamentalism arise out of Saudi Arabia, a brutal and theocratic society that happens to be a close American ally and oil partner?

Say what you will about the students who are sitting out the pledge, but I can guarantee you that these are the kids who are more likely to ask these kinds of questions. And they ask them because they think critically and care about the principles for which America is supposed to stand—blind obedience is not one of them. Pledging allegiance does not make one a patriot; one could even argue that it can inhibit the critical thinking needed for real responsible citizenship.

But unfortunately, as we are seeing, America has swung so far in the direction of an ask-no-questions, militarized version of patriotism that even its educators are too often not considering such questions. In fact, in some parts of the country school boards are even insisting that history be taught through a patriotic prism that is not critical of American actions.

This can’t be good news as we ponder the long-term direction of the country. Unfortunately, we’re reaching a point where critically thinking kids have fewer and fewer places to turn.