Why Are the Poor More Religious?

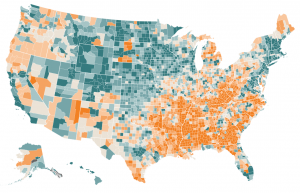

Map via The New York Times of where Americans are healthy and wealthy, or struggling. Learn more about this map here and learn more about the related web search terms study here.

Map via The New York Times of where Americans are healthy and wealthy, or struggling. Learn more about this map here and learn more about the related web search terms study here. Last week, the New York Times’ policy and statistics blog, The Upshot, wrote an article about the hardest places to live in the United States. The rankings, by county, included a variety of factors including education, income, unemployment, disability, life expectancy, and obesity. Based on the information, The Upshot identified ten counties clustered in the Appalachian and southeast regions of the country as the worst places to call home.

Interestingly enough, people living in these places are also more likely than those in wealthier sections of the country to Google search terms related to religion. The Google search terms common to these regions, which include “antichrist,” “about hell,” and “the rapture,” suggest that fundamentalism and its hellfire and brimstone visions of the apocalypse play a significant role in the lives of people who live in these impoverished regions.

These findings from The Upshot are reinforced by previous research into the connections between religion and poverty. According to a 2010 Gallup poll, there is a strong, positive correlation between strict adherence to religion and privation. But while the Gallup poll reports a link between religious devotion and poverty, it doesn’t provide any insight into why it exits.

A study by independent research Dr. Tom Rees, published in the Journal of Religion and Society, suggests that in places without strong social safety nets to provide people with opportunities for upward mobility, people are more likely to rely on religion for comfort. As contradictory as it may seem, when someone is suffering it may console him or her to think that the end of the world is near—that God will bring it to a close and reward the faithful with everlasting joy. Doom and gloom predictions about the trials and tribulations that humanity will face before the apocalypse, prevalent in Christian fundamentalism, may also help some people attribute a higher purpose to their suffering, explaining it as “part of God’s ultimate plan.” It’s also worth noting that in areas with little to no social supports, the local church may provide for people’s basic needs through free childcare programs, food pantries, and clothing drives.

Although religion can provide real assistance and a sense of security to disadvantaged individuals, that doesn’t mean it actually solves the problems associated with poverty. In fact, in an analysis of the aforementioned study, the British Humanist Association warned that government promotion of religion as a positive social influence could mask larger social problems that contribute to poverty, such as a lack of access to education.

Humanism, unlike fundamentalist religious ideology, is not concerned with hell or the nihilistic obliteration of a fallen human race. Instead, humanism is committed to ensuring that this life is the best that it can possibly be, since it’s the only life that any of us have. However, if we want to help improve the lives of people living in some of the “worst” places, we’re going to need more than rational arguments. We’re also going to need to ensure that people’s basic needs are met and that they have opportunities for security and advancement.