Sex and the Law: New Trafficking Legislation Endangers Sex Workers

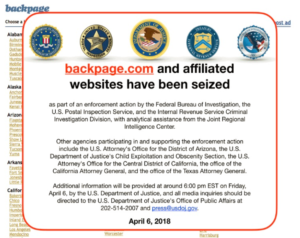

As part of efforts to combat sex trafficking, Backpage was seized by the federal government.

As part of efforts to combat sex trafficking, Backpage was seized by the federal government. On April 11 President Trump signed a pair of anti-sex trafficking bills into law that target online platforms. The House bill, called the Fight Online Sex Trafficking Act, or FOSTA, and the Senate’s Stop Enabling Sex-Trafficking Act (SESTA) target sites like Craigslist and Backpage that are often used by offenders as an aid to trafficking. Specifically, they remove the liability protection from web owners by making them legally responsible for the content their users put on their platform. For the past twenty years, Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act had protected owners from their users’ content. While this is no longer the case and is a victory for sex trafficking victims, it also presents a dangerous hurdle for those who work in the sex industry of their own accord.

The most immediate effect of FOSTA-SESTA is the removal of online communities for sex workers. Online communities are essential for this type of work, as they allow sex workers to safely screen their customers instead of turning to pimps or street solicitation and to communicate with other sex workers in referring each other to safe, reliable clients and warning about who to avoid.

Total removal of the ability to solicit sex via online platforms is not only increasingly dangerous for sex workers, but the Department of Justice also expressed concern that it obstructs pending trafficking investigations. FOSTA-SESTA intends to fight against online sex trafficking by removing these platforms and censoring web users, but that only drives sex work and sex trafficking further underground—enabling new ways of trafficking and making the industry even less safe. And how does FOSTA-SESTA combat traffickers when the web pages themselves are made liable instead of those who misuse them for trafficking?

This is similar to existing laws that criminalize clients and third parties of sex workers, such as “Toms” and owners of businesses in the sex industry. These laws seek to end sex work altogether by punishing the clients in an effort to wipe out the demand for sex work, which reinforces the idea that sex workers are victims. The victimization of sex workers is especially persuasive when we look at brothels, but we must differentiate between chosen sex work and forced sex work.

A major point of contention by opponents of FOSTA-SESTA is that it inadvertently conflates sex trafficking and sex work; they are not the same. Sex trafficking is when individuals and minors are forced, threatened, or abducted into sex work against their will. Sex work, however, is work individuals choose to do and have the freedom to stop doing at any time. As long as these two are treated indistinctly from one another, sex workers will continue to be criminalized and sex work will go unregulated. Whether we’re for or against the sex industry, we should all be on board with the fight to end sex trafficking. While this was evidenced by the bipartisan support for these bills, we should also become familiar with the discussion of destigmatizing and decriminalizing sex work and the communities affected by it’s criminalization.

Some individuals choose sex work because it pays better and allows more flexible working conditions than other jobs they might be qualified or considered for. Others choose this work as a means of expression. Those who are homeless, vagrant, or experience job instability for a variety of reasons may resort to sex work for their livelihood. Whether it’s a free choice or survival tactic, criminalizing sex workers makes them less likely to report violence and harassment by their clients for fear that they’ll be arrested. Further subjection to law enforcement can result in the even more abuse.

Criminalizing sex work also reinforces the idea that sex workers are hypersexualized deviants, unworthy of resources such as healthcare, housing, and employment. This stereotype is easy for the majority to believe—feeding into already established prejudices–as many sex workers are likely to belong to poor communities of color. We must recognize, however, the agency of consenting adults and be careful to not police sexual expression in the name of “saving.”

Advocacy groups for sex workers view decriminalization as the best approach to protect the health, safety, and rights of those who choose to do sex work, erasing penalties and allowing for regulations similar to other jobs. Sex work is not a violation of human rights. Sex trafficking certainly is, and knowing this difference allows us to identify actual trafficking victims and assist them without fear of criminal punishment—but only when sex work is decriminalized.