The Ethical Dilemma: A Muslim Employee Wants to Pray in His Office. Is This OK?

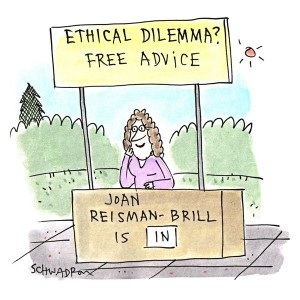

Experiencing an ethical dilemma? Need advice from a humanist perspective?

Send your questions to The Ethical Dilemma at dilemma@thehumanist.com (subject line: Ethical Dilemma).

All inquiries are kept confidential.

Muslim Prayers At Work: I have an employee who converted to Islam recently, and he wants to perform his prayers in his office, which he shares with another employee. He thinks his coworker is not comfortable with his prayers even though it takes only two or three minutes. He could go home to carry out his prayer rituals, but that would take about twenty-thirty minutes away from work time. If I give him this time off from work, it could affect other employees as well. They might think that we treat one person in a special way. I have no idea what to do.

—Caught In The Middle

Dear Caught,

It looks as though your email may be from outside the United States. If your company is based in another country, you’ll need to check what laws apply there. But if your company is in fact in the US (and for our readers who are), I’ve consulted with Jacob Small, an employment attorney who works with the Secular Legal Society of the AHA’s Appignani Humanist Legal Center. Following his comments, which contain a lot of legalese, I’ve added a few of my own.

In a nutshell, Jacob counsels that to avoid liability under federal civil rights statutes, you should permit the Muslim employee breaks for prayer, regardless of whether any other employees are uncomfortable with the practice. You should also take seriously any complaints of religiously motivated harassment or discrimination and act swiftly to put a stop to any such conduct.

He explains why: prayer breaks are likely a “reasonable accommodation” mandated by Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which applies to employers with fifteen or more employees. But that doesn’t mean anything goes if your company has fewer employees. “As far as I know, most states also have a state civil rights statute that has likely been held to be coextensive with the protections guaranteed by Title VII,” Jacob notes. “That is, it’s likely that in any given state, there are statutory protections similar to or identical to those guaranteed by Title VII but applicable for employers with fewer than fifteen employees.”

Title VII requires employers to make reasonable accommodations for the religious practices of an employee or prospective employee. The exception to this rule is that the employer can demonstrate that the requested accommodation would result in an undue hardship on the conduct of its business.

As far as an employer’s obligations to accommodate the religious practices of Muslims in particular, it gets pretty complicated. Jacob provides the details, citing EEOC v. JBS USA, LLC as an instructive case:

It considered JBS’s efforts to accommodate the following religious practices held by its Muslim employees:

“Muslims customarily pray five times per day. The Fajr prayer takes place in the morning, the Dhuhr prayer takes place at noon, the Asr prayer takes place in the afternoon, the Maghrib prayer takes place at sunset, and the Isha prayer takes place in the evening. Muslim employees differ in the exact amount of time it takes to perform each prayer, ranging from four minutes to, in some cases, more than ten minutes. During Ramadan, Muslim employees must break their fast with water or food or both after sundown. If a Muslim employee has gone to the restroom, passed gas, or touched someone of the opposite sex, ablution or cleansing is also required in connection with each prayer.”

The defendant in JBS argued that it had met its obligation to accommodate its Muslim employers because “they were permitted to pray before each shift, during regular breaks, and after each shift.” The court, however, held that “whether the prayer opportunities JBS provided are sufficiently close to Islamic prayer times so as to amount to a reasonable accommodation is a question best left to the fact finder and JBS fails to persuade the court otherwise.” It thereafter allowed the EEOC’s pattern and practice claims of failure to accommodate a religious practice to proceed to the jury.

This analysis might change if the employer could demonstrate that there was a legitimate burden to its business interests imposed by allowing the employee to pray at the times the employee is requesting. Nevertheless, this is an affirmative defense, and common sense seems to indicate that a two- to three-minute break at times that the employer is able to anticipate will not be burdensome and will instead be de minimus. Relevant inquiries would be whether other employees are permitted two- to three-minute breaks for things such as using the restroom, smoking a cigarette, or making a telephone call. In my estimation, prohibiting the Muslim employee from praying invites litigation. I would advise against it.

I also would be cautious about relying upon the biases of the Muslim employee’s colleagues as a defense to a potential failure to accommodate the claim. If the Muslim employee himself is afraid of this bias, and is thus requesting permission to leave the worksite for thirty minutes to pray, I think there is a possibility that the employer might be safe in denying that accommodation if the employer is willing to offer the accommodation of allowing the employee to pray at the worksite. The employer could protect himself even further by offering the employee a private location within which to conduct his prayers. Nevertheless, if I were the employer I would point to my written anti-harassment and anti-discrimination policies that contained clear guidelines for reporting, investigating, and stopping incidents of discrimination by colleagues and supervisors as sufficient protection for the Muslim employee’s right to pray without discrimination. I’m skeptical that the employee can cite an anticipated and speculative future discrimination as a reason for seeking a clearly more burdensome accommodation than the accommodation he might otherwise request: taking two to three minutes out of his work day to pray.

Damages under Title VII include (1) lost wages, (2) compensatory damages, (3) punitive damages for violations that are committed with the intent to deprive an employee of his federally protected rights or reckless disregard for those rights, and (4) costs and reasonable attorneys’ fees.

You should seek legal counsel in crafting an anti-discrimination and anti-harassment policy that protects all employees’ federally protected civil rights.

Did you get all that? Here’s my takeaway: Get thee to legal counsel. This is a can of worms you need to be very careful about containing. I see it as comparable (but way more potentially explosive) to dealing with a breastfeeding employee. The woman’s right to take care of her needs and preferences must be accommodated, while at the same time minimizing discomfort, embarrassment, and inconvenience both to her and her colleagues. Retreating to a somewhat private space for a reasonable amount of time, without shirking job responsibilities, should, in a perfect world, be sufficient.

Unfortunately, in our litigious and polarized society, an employer has to be prepared for a very imperfect world where it’s impossible to please everyone no matter what. As an employer, your role is to apply the rules as fairly as possible and follow the law to the letter.

In this particular case, however, it seems the Muslim employee projects that his coworker is uncomfortable—but you cite no evidence that the coworker is actually put off. Your employee is new to being Muslim, so it’s quite likely he’s hypersensitive and on the lookout for backlash that may or may not arise. As long as there’s no complaint on either side, just assure your Muslim employee that his prayers, which are his right, are no problem. And then, hopefully, everyone can go about their business.