The Humanist Dilemma: When Holiday Poetry Gets Faith-y at School

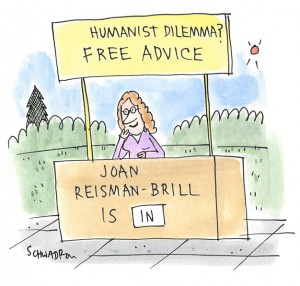

Experiencing a humanist dilemma? Need advice from a humanist perspective?

Send your questions to The Humanist Dilemma at dilemma@thehumanist.com (subject line: Humanist Dilemma).

All inquiries are kept confidential.

When To Make A Holy Fuss: I’m an atheist teacher in a very religious community. We have a big assembly for Veterans Day, and this year we are doing a choral reading in fifth and sixth grade. Part of the poem contains the lines “we pray God brings you home safely.” No big deal, or should I refrain?

—Shall I Mouth It or Mouth Off?

Dear Mouth,

We turned to AHA Legal Director David Niose to get his expert counsel. Here’s what he said:

This sort of thing—a reference to God in the context of a poem—would probably not be something that we would object to. We don’t like it, but courts generally tolerate what they consider to be harmless references to God that are in a musical or literary context, especially as part of a holiday celebration. If the “we pray” language were part of a daily or even weekly recitation, we’d be on more solid ground to object, but a one-time thing as part of a holiday event is probably too minor to justify our involvement.

That said, we would still encourage teachers and parents who find the language objectionable to speak up. The school should know secular families and teachers who find God-language problematic, and it’s possible that the school would revise the agenda for the event if even a few people speak up about it. If nothing else, a few vocal objections will make the school think twice about trying to inject religion into future events.

I believe you are also asking whether you should participate in reciting the objectionable words or remain silent. It’s your choice. Frankly, I doubt that anyone around you will even notice if you just go silent during that phrase, so it’s probably more a matter of doing whatever feels more comfortable or less uncomfortable to you. Saying the words may stick in your craw, but not saying them may make you feel self-conscious or concerned that if someone actually does realize that you are skipping the holy bits, they might possibly make some kind of trouble for you. So either you may prefer to just go along, or to take a little bit of a stand by not going along. It’s up to you to choose what seems like the better course in your particular situation, which may hinge on whether it is already known and accepted that you’re an atheist.

As David says, in this context the offensive phrase itself is no big deal. But there may be some value if you decide to voice your objection, not necessarily at the moment when the words are voiced, but before or after the assembly. Raising awareness that this kind of language bothers some of us may fall on deaf ears, or it might discourage the practice next time.