The Ethical Dilemma: I Overheard a Stranger Talking About Breast Cancer. Should I Have Said Something?

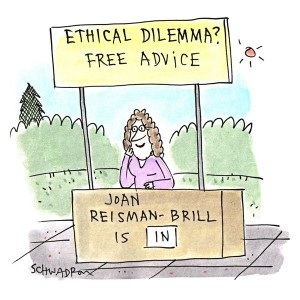

Experiencing an ethical dilemma? Need advice from a humanist perspective?

Send your questions to The Ethical Dilemma at dilemma@thehumanist.com (subject line: Ethical Dilemma).

All inquiries are kept confidential.

Conversation Bombing: I was eating lunch by myself at one of those restaurants with big communal tables. Three young women sat down right next to me, and one of them announced she had just been diagnosed with breast cancer. There were tears and hugs, and the girl was clearly in great distress. I had to squeeze by her to leave, and I had an impulse to put my hand on her shoulder (I’m female) and tell her not to be afraid, that everything would be all right. But I resisted and left without a word. Now it’s bothering me that I should have said or done something—even though I know it’s none of my business.

—Reaching Out Across the Table

Dear Reaching,

I actually had the opportunity to informally poll a number of people on this one, and we all agreed that basically you could do whichever felt most appropriate to you. In the case you describe, doing nothing barely edged out doing something. Now you regret it, so if a similar opportunity were to arise, I suspect you might opt to do something. The fact that the young woman made the announcement at a communal table, where interaction among strangers is encouraged, means you would not be overstepping to say, “I couldn’t help but hear, and I just want to wish you all the best.” And she might really appreciate that. But she also might feel you were butting in, so you run the risk of distressing her further or getting a rude response.

If the group were sitting at a separate table and you overheard, the same applies, but in that case it’s a longer stretch to reach out and a closer call to keep out. In any case, you need to read all the signals and go with what seems most appropriate. It also depends on whether you’re the kind of person who can summon a few (and only a few) comforting words naturally and positively. If not, keep them to yourself. And I would advise against any physical contact (e.g., hand on shoulder, hug) unless the other person initiates it. Avoid platitudes such as “Everything will be fine” when that may not be true. Better to say something genuine, such as “I hope everything goes well.” Even mentioning you know lots of people who have survived her illness may not be all that soothing, especially if she knows ones who haven’t, or if she has a dismal prognosis.

If, however, you can assist in a concrete way, such as providing entrée to an excellent doctor, or if you are a survivor yourself and want to offer your contact info, there’s more impetus to speak up. I once had an illness that terrified me until I was diagnosed and learned it was easy to control. But there was a lag between beginning treatment and when the tell-tale signs subsided. During this interim, I noticed a man and woman glancing at me and having some sort of argument. Finally they approached, the woman looking mortified while the man said, “Excuse me, I’m a doctor, and I couldn’t help but notice you have signs of Graves’ disease. Are you aware of that?” His wife jumped in to apologize for him, but I stopped her and explained that I did indeed know and was in treatment, but wished he had come along sooner, when I was walking around in dread of the mysterious syndrome afflicting me. I thanked him profusely for stepping forward to help a stranger, and assured him it wasn’t the least bit offensive.

Some people will recognize that you mean well, and you may succeed in making them feel a little better simply by showing you care. If others bark at you to back off, understand that they are agitated and it’s nothing personal. And then back off.

How To Help A Miserable Friend: I’ve been good friends with a woman for 25 years. We were out of touch for several months, and when I ran into her she told me she and her husband of 22 years were divorcing. She has always been a bit intense—an exuberant professional, fanatic exerciser, opinionated and outspoken. He is gentle, cerebral, inactive, overweight.

Her concern for her husband’s weight and sedentary issues turned to disdain, and she told me the last few years of their marriage have been filled with yelling and recriminations until he finally walked out, left her the house, and retreated to a peaceful apartment. You’d think she would be relieved, but over a long lunch, all she did was weep over being alone. Never mind that she has me and her adult children and legions of friends. She hates her life and her alone-ness, yet she drove her husband away and rejects him when he tries to help with household upkeep.

My question: She is so angry and depressed. My attempts at outreach are met with “You can’t possibly understand! My life is hopeless.” When I remind her she has friends who love her, she says, “It’s not the same. I can’t bear to live my life alone.” She’s seeing a therapist but rejecting pills (which I respect). Should I forge on, reminding her that I am here for her if she wants/need me? Or back off?

—She’s Alone Even Though Everyone’s Here For Her

Dear Here,

Yes, remind her, and yes, back off. Maybe she just needs time and space to heal. Or maybe not.

As I ponder your narrative, I can’t help but think about the husband, whose wife’s laser-like focus on his issues progressed from sympathy to scorn. I wonder which was the chicken vs. egg: Did he turn into a rotund couch potato before she started picking on him, or did he start withdrawing into food in reaction to her? Whichever is the case, he ran for his life, willing to give up the house that had her in it just to get away from her.

Now she’s bemoaning not the loss of her spouse, but her aloneness. And apparently she can imagine nothing in all the world that could fill that void—not reconciling with him, not her children, not you and all her other friends, and not a new companion who she is certain will never materialize. Not even mah jongg.

Unless this woman actually enjoys being unhappy (if that’s possible—it’s certainly a paradox), she has serious problems. Therapy is definitely in order, but she’s already doing that—with a negative attitude that’s likely to sabotage it. She is totally immersed in her misery. And her “legion of friends” will soon dwindle. Picture her wailing away her about her tragic fate to those who are divorced, widowed, otherwise partner-less, who don’t have a house or considerate ex-. Surely many of her friends have their own sad and sadder stories, yet they find ways to get on with their “lives that will never be the same.”

What you can do is what you have been doing: Reaching out and letting her know you are available to provide empathy and companionship if she’ll accept it. You could suggest some pursuits to take her out of herself, such as volunteering at the local hospital or women’s shelter, or getting that toned body into a sociable biking or hiking club. You might even suggest giving psychotropic medication a try, just to see if it could help her get a leg-up on this difficult passage. But be prepared to get your head bitten off at any suggestion that life could still be tolerable. Hopefully, in time she’ll move out of this wallowing and into something more productive. So invite her to call on you, and then let it go. If you want to check in periodically for a phone chat or lunch invitation, fine—but don’t feel guilty if you reach a point where you don’t feel like it. Sometimes you just can’t help people who don’t want to be helped.