The Ethical Dilemma: Should We Protest Offensive Works of Art?

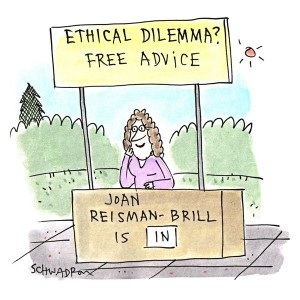

Experiencing an ethical dilemma? Need advice from a humanist perspective?

Send your questions to The Ethical Dilemma at dilemma@thehumanist.com (subject line: Ethical Dilemma).

All inquiries are kept confidential.

Death of Expression: A close friend recently participated in an organized protest against the opera Death of Klinghoffer. I was deeply disturbed by this—not because I believe that it was unwarranted (although from what I have read, I suspect it may have been), but because she knew nothing about the piece—only the information the organizers of the protest provided her with, which was cherry-picked to support their views.

My question is not specific to this particular production, but rather to the ethics of taking sides when you aren’t personally familiar with the subject in question. On one hand, I think it’s wrong to act based on other people’s interpretations of works of art. But on the other hand, to insist a person must see for herself would only sell more tickets, and encourage artists to create inflammatory works. What’s the ethical approach?

—Free Tickets For Protesters?

Dear Free,

I just encountered someone just like your friend, and when I told him I’d read that Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg was at the Klinghoffer opening night, he said, “You see, even she’s against it.” Not quite—she was there to attend the performance. My friend also was unaware that although this was the premiere at the Metropolitan Opera House, the work is not new—it has been performed around the world since 1991, and doesn’t seem to have made much of a dent after all those years.

You raise excellent points. The right answer cannot be that everyone has to see the work in question and then decide how they feel about it if they want to express an opinion. But I also question adopting other people’s conclusions, unless you have very good reason to trust their judgment. No one can personally research everything before accepting and acting on it. We rely on critics and friends to help us pick what shows we see, maps or GPS to tell us how to get somewhere, teachers and books and experts to tell us what has happened before our time or how many planets there are, the media to inform us whether it’s going to rain or if we can get Ebola from a bowling ball. None of these sources is 100% reliable, but if we don’t pay any attention to them, we’ll have a very hard time functioning in the world.

But running with a pack instead of thinking for yourself can have unintended, negative consequences. Have you ever found yourself in the middle of voting and realized you didn’t know a thing about any of the candidates for a particular office, so you vote by party, or gender, or for the one whose name is most familiar—then later realized that was not the candidate you would have picked had you done your homework? It would have been better to have left it blank than cast your ballot for someone you really wouldn’t have supported if you’d been better informed. Or have you ever found yourself jumping to conclusions, with the rest of the world, about who blew up a building, only to learn the “usual suspects” were completely innocent and victims of rampant prejudice?

When it comes to something as subjective as art, I’m inclined to say either see for yourself or abstain from the debate. Two people sitting side by side can come away from any performance with divergent takes on its meaning, which may have as much to say about each person as it does about the show itself. An individual can read a book (including a holy book) and get one thing out of it, and then re-read it and come away with an entirely different view—which may not square at all with the “conventional wisdom” or scholarly consensus about its meaning.

I am adamantly opposed to banning books, shutting down or disrupting shows, putting fig leafs on statues, or otherwise suppressing and subverting free artistic expression. If you don’t like something—or expect you wouldn’t if you saw it—it’s better to ignore it than to generate more powerful publicity than money can buy. If an author can’t include any slurs in characters’ dialog, or dramatize certain views (even if they may be vicious or false), or probe into uncomfortable controversies, then an awful lot of important topics will be off-limits. Even if a work truly is full of hatred and lies and distortions, if audiences can be brainwashed simply by being exposed to it, then there’s a much deeper, more alarming problem that needs to be addressed—and not simply by waving placards and chanting slogans.

Recognition For Diverse Volunteers: I am an ethnic Jew but currently non-practicing, and I am probably an atheist. I’m retired and volunteer in a Catholic hospital three days a week. Volunteers are honored once a year at a banquet. Some recent years, nuns have officiated the invocation, which was quite Catholic in tone. I have had some previous experience (elsewhere) with Catholic priests who delivered interfaith prayers quite generically.

Last year the officiant was not Catholic clergy and delivered a Christian-oriented prayer. This year’s officiant also was not Catholic. His prayer was nicely generic. However, his preceding remarks (which I cannot remember except for what I felt) at the beginning had me feeling like I was not welcome at the banquet and later had me feeling like I was not welcome as a volunteer.

I want to complain to the officiant (who works in the hospital). I would like some advice on how to respectfully phrase the complaint. I know for a fact that the hospital has volunteers who are of not only various Christian denominations, but also Jewish, Muslim, Sikh, and probably Hindu, Buddhist, and who knows what else. There needs to be some way to make the hospital’s representatives aware that they need to be inclusive.

—What Am I, Chopped Liver?

Dear Liver,

I have a similar problem with a struggling small-town non-denominational hospital that honors its donors—half of whom are Jewish—with a dinner that begins with holy-roller Christian invocations by the same preacher every year. I’ve brought this up with the woman who runs the event, who is ethnically Jewish herself, and she looks uncomfortable and cites tradition (I suspect she’s up against a board who won’t consider disinviting this old minister or instructing him to modify how he struts his stuff). So sometimes I stay out of the room until the rolling is over, other times I just sit and listen, eyes open, head up. This year he went on and on making entreaties to “Father God” and I nudged my husband and whispered, “At least it’s not ‘God Father.'” And he didn’t mention Jesus Christ for a change (maybe my chat with the administrator did have some effect). I won’t withdraw my support because the mission of the hospital is far more important to me than the offensive five minutes a year, and the Reverend probably doesn’t have very many years left.

But your case is much more disturbing. You volunteers don’t just write a check, you give substantial time and energy, so the powers that be must know you aren’t all Catholics. And yet you are collectively “honored” as though you all adhere to the religious aspects of the institution. Since there are different officiants each year, there is opportunity to bring in someone who can do a better job in the future. I suggest you make a complaint not to the recent officiant (who may not be in that role next time) but rather to the person in charge of organizing the event. And if possible, enlist some of the other disenfranchised volunteers to make your case with you.

Explain that the fact many of the volunteers are not Christian should not be denied—it should be respected and even celebrated. The diversity of volunteers is something to be proud of, not ignored. If the hospital cannot manage to embrace the backgrounds of its volunteers once a year at the very event designated to “recognize” them, perhaps there is another hospital or organization (school, library, community center, food bank, ) where you and your alienated colleagues would be more fully appreciated.