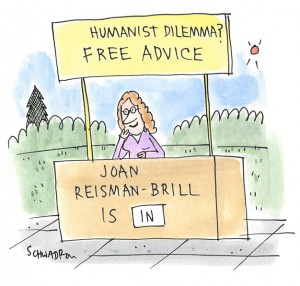

The Humanist Dilemma: For Crying out Loud! Some People Speak too Softly

Experiencing an ethical dilemma? Need advice from a humanist perspective?

Send your questions to The Humanist Dilemma at dilemma@thehumanist.com (subject line: Humanist Dilemma).

All inquiries are kept confidential.

I Can’t Hear You: Although I’m not quite officially a senior citizen, I’ve been troubled by not being able to hear certain people as long as I can remember. Every few years I’ve had my hearing checked by reputable professionals, and every time I’ve been told I have some minor loss but that it’s in the normal range and not anything to be addressed with hearing aids or other measures. Most recently my doctor gave me such tips as sitting with my back to the wall in noisy restaurants, which I’d never thought of, or facing the person who is speaking to me, which seems to go without saying.

Yet there are certain people I repeatedly spend time with and can never hear. When I tell them, they just repeat exactly the same way, become impatient with me, or just prattle on. Meanwhile, as much as I’d like to have a conversation, I get frustrated and stop attempting to engage with them, and even keep my distance when I anticipate we won’t be able to communicate.

My doctor says it isn’t me, it’s them. But what can I do? I find myself not wanting to greet these people when I see them, and I’ve been thinking about avoiding situations, like noisy restaurants and parties, where these things are likely to happen with them or others.

Is there anything I can do short of handing people a megaphone or cupping my ear and going “Eh?” like an old fart?

—Speak Up or Don’t Speak

Dear Speak,

I know exactly what you mean. It’s the hairdresser who’s blowing a dryer in your ear while asking you a question (such as, “Is this too hot?”); the driver facing forward, with the radio blasting, asking you in the back which airport; the waitress in the trendy high-decibel restaurant rattling off the specials from across the table; the person at the party using their indoor voice despite the outdoor din.

When I was traveling in foreign countries, I was complimented on my English. When I asked what was special about it, I was told that most Americans spoke rapidly, ran their words together, and used slang, whereas I spoke English distinctly, using the vocabulary and grammar they were taught in school. In fact, I always consciously modify how I speak when my listener’s English is a second language. I try to enunciate (but in that case wouldn’t raise the volume of my voice). The same courtesy should be extended to anyone who’s having trouble understanding another. To do otherwise is thoughtless, rude, and even cruel. People who are shut out of conversations feel frustrated and isolated, and it can affect not only their enjoyment of life but also their ability to survive and thrive in the workplace, at school, socially, and generally while conducting the business of living.

There are a few things you can do, some of which you’ve probably tried. First, there’s “I’m sorry, I didn’t hear you. Could you repeat that/turn down the radio/come closer/face me/speak slower and louder?” If that doesn’t work, escalate to “I’m sorry, I still can’t make out what you’re saying. Can you try rephrasing or enunciating more clearly?” After that, you can be a bit more confrontational: “If you really would like me to hear what you’re saying, you need to make more effort to be audible to me.” And finally, you can announce, “I’m sorry, I’m really trying but failing to hear you, so I’m going to exit this conversation.”

I don’t know why some people behave as though a person who doesn’t hear them is annoying or lazy or stupid or old or inferior. I also don’t understand why certain people consistently speak in a soft voice with their words run together, and keep doing so no matter how many times they’re told they aren’t being understood. Sometimes it’s ok to smile and nod without really hearing, but then you run the risk of appearing to agree with something you don’t, or to give an inappropriate response to something like “my mom died” or “your wallet just fell out of your pocket”. In most cases it’s preferable—and shows interest in what the person has to say—to let it be known if you’re not getting it.

As you note, if people really want to communicate with you, they should make the effort to speak louder, slower, rephrase, move to a quieter area, etc. Don’t let anyone make you feel bad about yourself if they aren’t making themselves heard. Regardless of whether you have a clinical hearing deficit, it’s unkind and unfair for anyone to treat you disrespectfully because you have trouble deciphering their words. Don’t avoid social situations or accept isolation because some individuals won’t meet you half-way. Turn away from those you can’t hear and toward those you can.

There are organizations such as the Center for Hearing and Communication (chchearing.org) that are working hard to make it easier for people with hearing impairment to enjoy theaters, shows, and daily activities. Check out their website, which has a wealth of great information about hearing problems and solutions. It’s not just about technology, which cannot yet solve all hearing problems. Audio assist devices must be teamed up with polite insistence on considerate behavior toward those with hearing issues. Those of us whose hearing is fine for now ought to pay it forward, as hearing loss will affect most people eventually.