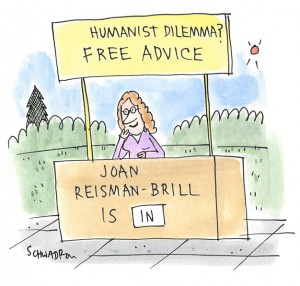

The Humanist Dilemma: How Does a Secular Doctor Respond to a Patient’s Prayer Request?

Experiencing an ethical dilemma? Need advice from a humanist perspective?

Send your questions to The Humanist Dilemma at dilemma@thehumanist.com (subject line: Humanist Dilemma).

All inquiries are kept confidential.

Professional Praying? As a psychotherapist I found this article interesting (“How to Respond to a Patient’s Request for Prayer: A Clinician’s Dilemma”). I wonder what response you would recommend for health providers who are humanist, atheist, or agnostic if a patient requests that they pray with or for them.

The article cites a case study published in the AMA Journal of Ethics that

reviewed the ethical dilemmas posed by a patient’s request for prayer before a scheduled bypass surgery. April R. Christensen, MD, of the division of general internal medicine, department of medicine, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center in Pennsylvania, and colleagues, reviewed the case. The surgeon in question is a secular Jew and atheist who felt uncomfortable when the patient, a devout Catholic, requested that she pray with her. The surgeon suggested calling the chaplain, and the patient felt rebuffed.

Dr. Christensen and colleagues suggested that rather than immediately trying to deflect the patient’s request, a physician should pause to internally examine why the request makes them uncomfortable and their own emotional response to the request. The investigators also noted that there are ways to deal with this situation that both honor a patient’s faith and maintain a physician’s boundaries.

—Is Praying Part of My Job?

Dear Job,

It’s intriguing that the response in the case study tossed it back to physicians to examine, or re-examine, their own reluctance to pray and the patient’s deeper motivations underlying the request. I find that a bit disconcerting, as though there’s something the matter with clinicians who are unwilling to participate. Although it might be constructive to do the prescribed soul-searching, I expect busy physicians aren’t prepared to grapple with such questions when patients put them on the spot. Nor do I think there’s anything wrong with clinicians who do look inward (or are confident they needn’t bother) and recognize they are sincerely, deeply uncomfortable with professional praying.

It strikes me that referring the patient to a chaplain did indeed, as the authors state, honor the patient’s faith while maintaining the physician’s boundaries. In contrast, admonishing physicians to examine why they themselves object, and to probe the emotions and circumstances underlying the patient’s desire to have them pray, violates the physician’s boundaries.

I don’t see anything wrong with healthcare professionals firmly maintaining that praying is not part of their job, but rather the bailiwick of spiritual or religious professionals. Most hospitals have chaplains and other counselors on staff. In fact, when I was in the hospital a few years ago, I was trying to figure out how I could get a restraining order against the parade of chaplains who kept popping in to pray at me. And I would feel much less confident if my surgeon invoked divine guidance.

Certainly, some non-religious professionals have no problem praying with or for patients if asked, and that’s perfectly fine. To them, it’s a favor that costs them little or nothing but greatly comforts the patient. But others would feel dishonest and compromised doing something that is incompatible with the science that undergirds their work or their personal ethics. And that’s fine too, even if it may disappoint some patients. As long as the professional is polite and kind, refusing to pray—while suggesting the patient seek out someone more appropriate—should suffice.

Perhaps in this particular case the patient felt rebuffed because the physician’s manner was brusque. Or perhaps the patient was (understandably) hypersensitive and irrational due to fear about the upcoming surgery.

If there are any guidelines for such situations set forth by the relevant professional organizations (medical, psychiatric, psychological, social work, etc.), practitioners should be familiar with them. But even if they exist, they are most likely suggestions, not requirements. I can’t imagine any secular professional organization insists professionals comply with patient requests for prayer, particularly in violation of their own principles.

Although it’s natural for patients to feel vulnerable and seek reassurance from their doctors, a request for prayer is misplaced. A demand for expert counsel on their prognosis or the outcome of their treatment is appropriate. What if patients asked their doctors to comfort them by staying with them the night before or after their surgery, or to take care of their plants or pets or children while they’re convalescing, or to put in a word with estranged relatives? No one would expect doctors to comply with those requests–only to refer the patient to those whose role encompasses such things. The same should be true for prayer requests.

Physicians and other clinicians are under pressure to fulfill an array of challenging demands: Are they competent? Is their diagnosis accurate? Is their treatment plan optimal? Are the risks and expected outcomes reasonable? Do they listen, answer questions, and explain things comprehensively and clearly? Those are just some of their professional responsibilities. Praying on demand (or justifying why not) is not.