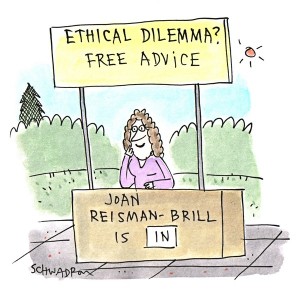

The Humanist Dilemma: Is Tolerance Intolerable?

Experiencing an ethical dilemma? Need advice from a humanist perspective?

Send your questions to The Humanist Dilemma at dilemma@thehumanist.com (subject line: Humanist Dilemma).

All inquiries are kept confidential.

In response to last week’s column on shunning, harassing, and refusing service to people whose views we abhor, one reader advocated Karl Popper’s paradox of tolerance, and another advocated rejecting it. According to Wikipedia, “the paradox states that if a society is tolerant without limit, their ability to be tolerant will eventually be seized or destroyed by the intolerant. Popper came to the seemingly paradoxical conclusion that in order to maintain a tolerant society, the society must be intolerant of intolerance.”

This is certainly an idea worth contemplating, and I invite readers to discuss it in the comments section below. It’s a critical consideration both for those who argue to “go high when they go low” (thank you, Michelle Obama) and for those who demand aggressive resistance and pushback against divisiveness, discrimination, bullying, and violence.

Not only do I struggle with this paradox, I struggle with articulating that struggle. But then, I guess that’s how paradoxes work. So, with a layman’s grasp of the concept, I’ll give it a try.

I’ve always had difficulty with the idea of being tolerant or respectful, or even polite or silent, when confronted with views that I find ridiculous, false, cruel, abhorrent, or otherwise objectionable. I chafe at politically correct responses to positions I deem misguided or odious. I am troubled by allowing other people to fill their children’s minds with fantastical or hateful notions, even if that’s their right as much as it’s my right to teach my children to be reasonable, skeptical, and generous. I have a hard time holding my tongue when others flap theirs with assertions that make my head explode.

But I also recognize that being intolerant—verbally or physically attacking or shutting down those with whom we disagree, however righteously—leads to escalating conflict. People who feel silenced, ridiculed, overpowered, or threatened are less inclined to reconsider the wisdom of their views and more inclined to dig in and double down.

I recently took a course on Homer’s The Iliad, about a long and devastating war that was sparked when a guest abused his host’s hospitality (i.e., a visitor from Troy made off with a Greek king’s wife, Helen). The thinking was, if the Greeks were to tolerate this breech of civil convention, Greece would appear weak, inspiring Troy and other nations to dismiss their authority and even to turn against them. The same would happen to the Trojans if they apologized and returned Helen (and her dowry). Many others countered that it was ludicrous for men to go to war—abandoning their own families and sacrificing many lives plus valuable resources—over one man’s wounded pride. The story has stood the test of time because there is no simple right or wrong response among myriad nuanced perspectives.

Although I hate the idea of war, I believe there are times it’s a necessary evil, such as to stop the Holocaust (or any holocaust) or to end slavery and other forms of oppression. Tolerating despots only allows them to usurp more freedoms, injure more innocent people, and consolidate more power. Today we are witnessing very disturbing infringements on our constitutional rights, our most cherished values, and our most downtrodden fellow humans.

How can we tolerate people whose sincerely held beliefs include the conviction that certain individuals and groups should not flourish or exist because of their race, religion, sexual orientation, political affiliation, position on women’s rights, poverty, etc.—particularly if those people are inclined to act on their beliefs in ways that encroach on our own?

When I think about this issue, I think about how radically different approaches during the Civil Rights movement—e.g., Martin Luther King Jr.’s nonviolent resistance vs. Malcolm X’s more militant approach—may have had complementary effects in bringing about their shared goals. Perhaps the same is true of any conflict—a mix of tactics may be more effective than any one alone.

Popper’s paradox would be powerful if indeed the tolerance were, as it posits, “without limit”—if everyone on one side remained tolerant no matter what, while the other side was merrily running roughshod over them. But the hypothetical idea, “what if everyone did X,” is always countered by the reality that not everyone will do X. There will be limits. Some of us, no matter what side we’re on, are inclined to be engaged, reasonable, understanding, and willing to absorb figurative or even literal blows. Others choose to stand their ground, not give an inch, and push their agenda forcefully. Such a cacophony of responses would prevent any group from completely and permanently overtaking another, which is at once both reassuring and frustrating. No matter how much progress is made with many issues we thought had either been resolved or were moving in a positive direction (for example, same-sex marriage, abortion, race relations, eradicating measles), we keep finding ourselves back in a tug of war over questions we thought had already been settled.

In a Time magazine review of the new film Sorry to Bother You, Stephanie Zacharek observes, “We want to do the right thing, but we’re not sure what it is. We don’t want to be insensitive, but being sensitive means lowering our guard—can we afford to do that?…Doing the right thing always involves risk. Get ready.”

Readers: How do we strike a balance between sensitivity and keeping our guard up against overwhelming intolerance? How do we ascertain the right thing to do?