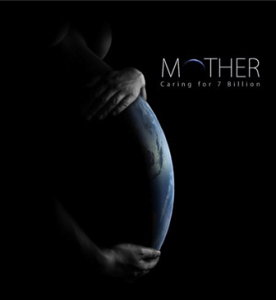

Film Review: Mother: Caring for 7 Billion

Mother: Caring for 7 Billion is a clear-eyed documentary on the often controversial topic of the long-term effects of human population growth on humanity’s ability to sustain itself in the face of the finite natural resources of the Earth. While clocking in at just under an hour, the film has a breathtakingly wide scope and breadth in the topics it addresses, especially environmentalism, family planning, feminism, agriculture, consumer culture, religion, and international development. It is Mother’s complex examination of the intersections between these different themes, its stance that all of humanity must work together to empower women to advocate for their reproductive rights, and that we must also work together to develop ethically responsible strategies to conserve the Earth’s natural resources that make it a distinctly humanist film.

The film often shies away from offering a unifying narrative voice and instead relies on direct testimonies from humanitarian experts, scientists and environmental advocates, in addition to featuring interviews with women in developing countries. This strategy allows a critical viewer to independently examine the political backgrounds of the various experts and come to their own conclusions rather than being subjected to a narrowly-defined ideological stance of wrong vs. right, such as in the populist documentaries of Michael Moore.

The film begins by centering itself in a historical re-examination of the “green revolution” of the 1960s, which refers to the boom in both agricultural production and population growth in developed countries that occurred thanks to industrialized farming methods and a seemingly endless supply of fossil fuels. Yet this “green revolution” could also refer to the various environmentalist and anti-population growth movements that sprung up to voice the concerns that such growth, and the consumer culture it was based on, was both ecologically unsustainable and ethically irresponsible, as exemplified by the first Earth Day protest on April 22, 1970.

Mother asserts that controlling population growth is a key environmentalist issue that has been almost forgotten over the decades since 1970 at great peril to humanity, especially as the rest of the developing world looks to the consumer patterns of the middle-class in the U.S. as a model. If the rest of the world bought and used as much consumer goods per-capita as the U.S., it would take six Earths to replenish and store all the natural resources needed and waste created. And, as the film asserts, with 78 million more people living on the Earth each year and 50 million new people joining the middle-class each year, worldwide consumption patterns create a “ticking bomb” scenario.

Indeed, Mother draws its particular strength from its unflinching examination of why population growth is often such a taboo subject in society, and Mother’s rejection of any solution that denies to women their basic reproductive rights—both their right to have children and their right to birth control and family planning—makes it a humanist film rather than a purely environmentalist film. A key fact that the film-makers go to great length to illustrate is that “in almost all countries the desired family size is lower than the actual family size,” and furthermore, “215 million women worldwide who wish to have smaller families [are unable to do so] largely because of informational or cultural barriers.” These barriers include fathers, male partners, religious leaders, lack of education, and other societal forces that coerce women into not seeking access to birth control and/or otherwise leaving reproductive decisions ‘up to God.’

Riane Eisler, president of the Center for Partnership Studies and recipient of the American Humanist Association’s Humanist Pioneer Award, emerges as one of the most powerful voices in the film as she challenges viewers to “start talking about that vexing thing called gender.” She alongside other women such as Esraa Bani from Population Action International, advocate that in order to address population growth, we must first elevate the position of women not just by imposing “Western ideologies” but, as Bani advocates, “from within their culture, within their religion, they have rights. But they don’t know…we can start from within the culture, and then go the next steps.”

The film’s most moving moments comes from its case study of a very successful educational initiative in Ethiopia by Population Media Center that uses serial radio dramas to provide women with powerful role models for how to stand up for their rights and freedoms in a country with deeply entrenched cultural values that often make birth control inaccessible. One particularly inspiring young woman, Zinet Mohammed, gives an impassioned testimony to how the radio drama changed her life and that of her family of 14 that “ate only once a day.” First she relates tearfully to the camera how listening to the radio drama made her seek out birth control for her mother—her father initially was resistant but changed his mind after Zinet brought both to the hospital and the doctor convinced her father that “the pill works.” Zinet later relates:

I had a chance to marry a rich man, but I said no. The character’s life from the radio drama taught me a lot, so I told my parents that I wouldn’t marry that person… After that my father listened to the radio dramas. He regretted a lot that he tried to force arranged marriages on his daughters.

Her father then explains to the camera how her entire family now looks up to Zinet and that she also is the primary provider for the family. Dr. Negussie Teffera, Population Media Center’s country representative for Ethiopia, further explains that as a direct result of the radio drama “we have received more than 30,000 letters from all over the country…demand for contraceptives has increased 157%. Spousal communication had also increased from 33% to 68%.”

The film’s conclusion wrenches the viewer back from its specific focus on Ethiopia to a sweeping historical and political examination of the various systems of oppression that allow, and even encourage, unbridled human population growth. Mother ends with a very strong environmentalist call to action that is less specific in offering solutions than its examination of feminism, but a stance that I personally agree with nonetheless. All in all, Mother is an excellent humanist film that urges humanity to work together as “one human family, connected in our challenges, connected in our solutions” to challenge oppressive systems such as sexism, classism, corporatism, and neo-liberal globalization through inter-connected social movements that demand social justice and ecological responsibility.

To learn more about Mother: Caring for 7 Billion, or to find a screening near you, visit www.motherthefilm.com.

To learn more about Mother: Caring for 7 Billion, or to find a screening near you, visit www.motherthefilm.com.