Evolution, Humanism, and Conservation: The Humanist Interview with Richard Leakey

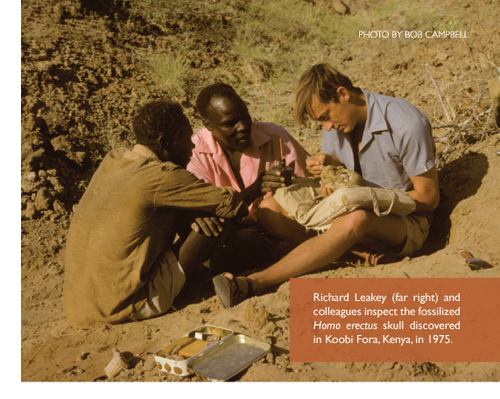

Richard Leakey is a world-renowned paleoanthropologist whose career has been marked by famous scientific finds, political office, and conservation efforts. His family is equally accomplished in the field of anthropology, starting with his parents, Louis and Mary Leakey, as well as his wife, Meave, and their daughter, Louise. Richard originally made his mark in the late 1960s and ’70s with expeditions that discovered Paranthropus boisei, Homo habilis and Homo erectus skulls as well as the discovery of Turkana Boy in 1984. In 1989 he left his duties as director of the National Museums of Kenya upon receiving an appointment from Kenyan President Daniel Arap Moi to what would become the Kenya Wildlife Service. In his efforts to protect Kenyan’s national parks and wildlife, Leakey brought global attention to the plight of Africa’s elephants by helping President Moi burn twelve tons of ivory (worth $3 million) in Nairobi National Park. In 1993 a small plane Leakey was piloting crashed and both his legs were amputated, and to this day he walks on artificial limbs. After resigning from the KWS, he served as secretary general of the Kenyan opposition party Safina, and in December 1997, he was elected to the Kenyan parliament. Two years later Moi appointed him head of Kenya’s civil service where he was tasked with combating mismanagement and corruption within the government. Leakey now splits his time between Kenya and New York, where he is chair of the Turkana Basin Institute at Stony Brook University.

In May, Leakey made headlines with a prediction that in ten to fifteen years the evolution debate will be over. He was in New York City to promote the Turkana Basin Institute and attended a benefit concert given by his friend Paul Simon. Leakey told reporters: “If you get to the stage where you can persuade people on the evidence, that it’s solid, that we are all African, that color is superficial, that stages of development of culture are all interactive, then I think we have a chance of a world that will respond better to global challenges.” This past fall, I spoke with Leakey about his various activities, and his philosophy regarding science and religion. Besides his academic and conservation work, Leakey is a humanist who has long supported rationalist associations and advocated for teaching evolution in public schools. Typical of Leakey’s reputation, he did not hold back on his opinions and gave insight into current social issues.

The Humanist: In your 1984 autobiography, One Life, you explore the influence your parents had developing your interest in learning and science. At one point you write: “The joy of searching for fossils in remote and difficult places is that there is always a strong possibility that each ‘find’ will tell you something new.” Why are these discoveries important to society?

Richard Leakey: I think increasingly we face a world where there is evidence for dramatic and consequential environmental change. Consequent to that are changes to survivability and the very existence of a number of species. If you look back at the prehistory and ancestry of humans and close relatives—the chimps, the apes, the monkeys—and you go back even to the history of elephants, rhinoceroses and antelopes, it is very clear that although evolution happens because of climate change, the great effect of climate change is in fact the number of species that become extinct.

By understanding the relationship between extinction and climate change in looking at ancient environments and recovering material from them, I think we can get a much better sense that this climate change isn’t merely of interest to the commercial side of oil development, or the government side of keeping the demonstrators off the street on green issues. It is really an issue of long-term strategic planning for how the world is going to feed itself through government and non-government agencies.

The Humanist: Why is it so important for people, not just scientists, to learn about evolution?

Leakey: What makes us different from every other living organism we’re aware of on this planet is that we have the capacity to think. We know that we exist. We know we didn’t exist at one stage. We know we won’t exist after a certain point in time. By understanding and getting answers to questions, I think we can be a much more unified and cohesive group.

Leakey: What makes us different from every other living organism we’re aware of on this planet is that we have the capacity to think. We know that we exist. We know we didn’t exist at one stage. We know we won’t exist after a certain point in time. By understanding and getting answers to questions, I think we can be a much more unified and cohesive group.

While faiths do provide answers for some people, they are rather like fairytales. They are culturally influenced and have very little staying power. Although people would argue that Christianity has been around for a couple thousand years, and Islam and Buddhism for probably an equal amount of time, Homo sapiens has been around for 200,000 years. So it’s a microscopic amount of time that we’ve been affected by religion.

Two and two making four, or the issue of gravity keeping us on the planet and affecting the way trees grow and get sunlight—these scientific phenomena have been around forever. I think the principles or the processes that have led to us being what we are can be understood in the same terms. It’s not a matter of taste or faith. We should have a scientific explanation for why we are here, how we came about, what led to our ability to walk, to make things with our hands, and to develop technology. We should be able to explain scientifically what gives us our capacity to influence each other and our planet.

I believe that the human mind has always sought answers. Faith-based answers are simply no longer adequate for the majority of our species.

The Humanist: With Richard Dawkins you’ve discussed problems associated with teaching evolution in Kenya. How does opposition to evolution in Kenya compare to the United States?

Leakey: In Kenya we have a much smaller population. Under 20 million of 40 million, or let’s say less than two-thirds, attend school in some form. So a very small number are educated, and in a small country we depend highly on those who are educated to take up positions. If the majority of schools are teaching students that evolution—the change of life forms through time—is purely fictitious, that there is no scientific basis in which we can understand life, how are we going to produce physicians who can look at pathogens? How are we going to produce agriculturalists who understand that the misuse of pesticides can create new strains of disease? How are we going to look at the new diseases and pandemics that result from the misuse of antibiotics? How do we expect young kids to come out and study why tuberculosis is becoming drug-resistant? We cannot afford, as a nation, to have the majority of our young people going forward to college and beyond simply rejecting science.

In Kenya religion is used to suggest that God or gods are so powerful that we don’t need science; that the fate of Kenya and the fate of individuals are in the hands of God. In the United States, with its much larger population, its enormous range of educational opportunities, and its tradition of diversity, the extremes probably have far less influence on the uptake of the young minds in science than you’d see in a small country.

The Humanist: In the United States there are major organizations such as Answers in Genesis, which built the Creation Museum, that actively counter the teaching of evolution. Are there equivalent organizations in Kenya?

Leakey: Fortunately not. We don’t have resources to produce the quality exhibitions that perpetrate lies.

The Humanist: How do African scientists and educators respond to creationism? Is there a Kenyan equivalent to the National Center for Science Education, for example?

Leakey: No, there is no organized response to it. I think the majority of people who teach in school are closet rationalists. They have relatives and family who are totally committed to a faith-based way of life. The reality is that if you stand out and say you don’t believe in all their clap-trap, that you are basing your life on scientific grounds, you will suffer as a social outcast. So there is relatively little that is done to counteract and counterbalance the weekly Sunday (or more frequent) programming to produce narrow-minded, faith-based people who expect their problems to be resolved by the so-called Almighty.

The Humanist: When creationists deny evolution they, in many cases, ignore the fossil evidence. How would you describe the amount of work that scientists do in researching for an expedition, describing and categorizing a find? How would you tell a creationist about that?

Leakey: The more important point is the one Charles Darwin and others of his day made, which was to say: look, we have fossilized remains of things that were clearly living at one time. They are imbedded in geological strata such that, under the laws of time succession, the ones at the bottom will be older than the ones on the top. Therefore, if you look at the remains from the lowest strata to the upper strata at a given place and there is a long enough time represented, you see things change. As you come nearer to the present you see things that are more like those living today—not just humans, but all forms of life.

The fossils and the geology are factual, not theoretical. You can feel them, measure them, and hand them to each other. Now we can date the sections and know when these things happened. What Darwin did was suggest the process in which this change happened. Certainly in Genesis there is no evidence that God went through many eras of trying out new experiments that he then wiped off to try again.

Darwin coined the idea of natural selection to explain the change mechanism and he called that evolution. You may say evolution is therefore a theory. But it’s a theory that explains a lot of facts. In other words, it doesn’t make the facts non-existent. Many people forget the evidence that life has changed through time is as solid and as definite as anything in science.

Why, over 50 million years, did an ancestral elephant with four incisor tusks become a series of species of large elephants with two tusks? Why at some point do we find giraffes with long necks when their ancestors had short necks? What led to these changes is open to the theoretical explanation, but that they have changed is a fact. That the change is not addressed in Genesis is a fact. Similarly, Genesis doesn’t deal with gravity. It doesn’t deal with the fact that we can transmit messages through the air and cyberspace, or fiber optics. It is utterly pathetic, in my mind, that in the twenty-first century educated people still have a need to deal in fairytales.

The Humanist: Notably, you’re the grandson of Christian missionaries. How did you come to be an atheist?

Leakey: There is a common concept that we don’t choose our parents and we certainly don’t choose our grandparents. I never knew my grandparents, but clearly when they were young the idea of evolution was just in the early stages of being discussed. There were a great many people in Britain who felt that the work of God, spreading the Gospel, was necessary to a life of compassion and of concern. They felt that part of God’s work was to give people living across Africa God’s word so that they could be saved. I think there was a zealous and sincere commitment to go out and do these things. What I find extraordinary is that many of the European conquests of foreign lands to spread the Gospel involved massive slaughters and destruction of civilizations. The slaughter of innocent women, children, and men out of battle just to take over land and establish authority to make these people go to school and learn the word of God seems to be a contradiction. As the first president of Kenya said, in order for the Christians to come into Kenya and spread the word, they had to break several of the Ten Commandments before they got off the ships.

The Humanist: Do you link atheism to your background in science? Were you ever religious?

The Humanist: Do you link atheism to your background in science? Were you ever religious?

Leakey: No, I’ve never been religious at all. Reading the scriptures was mandatory in my childhood but I’ve also always believed that you should know what it is you don’t believe.

I don’t mind being called an atheist, but I think the term is very specific and focuses you on the “G” question. I think there is much more to it than that. I don’t need any sense of a final place or final retreat, or anyone outside me to help me. I’m a rationalist in that sense. I like to understand why things happen. If I understand why things happen I can then try to intervene to make sure the course of the happening is influenced for social issues. Certainly you cannot be a rationalist in the strict sense of the word and not be an atheist. I’d say I’m a rationalist and a humanist, in terms of having principles and a philosophy of life that doesn’t require any point whatsoever for a supernatural entity that ultimately controls the outcome of my life or anybody else’s.

The Humanist: You’ve faced the possibility of death several times in your life: fracturing your skull, risky expeditions, a failed kidney, and the plane crash. Has the fear of death ever shaken your rationalism? Have you ever had any point where you thought you might’ve believed in a supreme being?

Leakey: No. I think one would almost say those scrapes with death reaffirmed my conviction that there wasn’t a God. It’s true that I probably had what they call a “near-death experience” where you feel as if you’ve left your body. I can remember distinctly entering a conscious state where I’d never been before. The answer is my oxygen supply was cut off because my lungs were damaged, and the system of synapses in the brain and whatever else goes on was just closing down. There was this moment when, had I been looking for angels, trumpets, virgins, and the like, I would have seen them. In retrospect I was intrigued by what was happening to me because I had never felt myself levitating and watching a body that I knew was mine, and listening to the talking, but not being there.

This kind of out-of-body experience is very common and is a very real experience. I’ve been through it twice, once more vividly than the other, but in neither case was God involved. There was no sweet music, no “come to the gate,” or “since you did this at that moment you are going left as opposed to right.” Absolutely not. It was a very strong analgesic to limit the amount of pain when the system closed down. When the doctors revived me I became conscious that I was alive again because I could feel the pain from my lacerated lungs.

You can see why people could easily believe in a better life when those who’ve had out-of-body experiences (and they must go back two or three thousand years, if not well before) say, “I saw God, I heard the angels piping for me, I was in a lovely place,” but that lovely place is purely the closing down of the brain.

The Humanist: After the 1993 plane crash, President Moi told you that he would pray for you, and your reaction surprised him. What did you say?

Leakey: Well, I’d been trying to get him to sign a presidential order I’d drafted to give the Kenya Wildlife Service the legal right to hire people at salaries that were pegged to the private sector, rather than the government sector. I was looking to attract good people to work for the organization, and it required presidential consent to do this. He had been sitting on my request for several months and it just happened to be that’s what I thought of when he appeared so amenable to please. Even though I was rather unwell, the first thing that came to my mind was, now I’ve got you in front of me why don’t I ask you to do this. Given my condition and given that he was a very religious man, I think he felt I rebuffed him in a rather rude way in the presence of nurses and his entourage when I said, “I don’t need prayers. Don’t pray for me, but please sign that piece of paper.”

The Humanist: You signed the Council for Secular Humanism’s 2000 Humanist Manifesto. What does humanism mean to you?

Leakey: To me it’s a recognition of people who don’t believe in a deity, but who believe we must manage our affairs based on what we are as a species and our position on this planet. As I said earlier, atheism tends to have a somewhat pejorative connotation in discussion. If you don’t believe in a god then you must be barbaric, you must have no morals, and so on.

I think we humanists are perfectly aware of the need to not stab somebody who irritates us, to not run someone over because they’re in the middle of the road, and to not tell lies so we can benefit ourselves. I believe in honesty, integrity, compassion, love, and care of others in the world. It is a rationalist approach to life that isn’t dictated by a super power or super being, or a deity or a mystic. It is dictated by our common sense, and to label that as humanism has helped a lot of people.

If you say you’re a humanist you don’t immediately raise the hairs on the back of the neck of the zealots in religion. I don’t think it’s a cop-out. Even so, I don’t go around saying ‘I’m a humanist, here I am.’ I don’t think I need to, but if asked to choose a label I’d say humanist and rationalist.

The Humanist: Humanist organizations tend to be fairly small. How can humanists better voice their message?

Leakey: I’m not even sure humanists need to voice their message. We don’t have to persuade anyone to be a humanist. When irrationalists, as opposed to rationalists, start suggesting that children shouldn’t be exposed to science, to biology, and the idea that life has changed, and instead promote the biblical version of how we came to exist, then I think we should speak out. You can recognize there is a difference of opinion, recognize that people don’t like the idea of evolution as a theory, but by the same token they have to accept that life has changed. Their version can’t be tested, our version can.

So I don’t know if we want to convert people to humanism and rationalism. I want to just make sure people have an idea of reality and make decisions on the consequences of reality, rather than the hope or prayer that at the end of the day they’ll be taken care of anyway.

The Humanist: Does that make humanism a more defensive philosophy if humanists and rationalists are coming out in reaction to what religious zealots are doing?

Leakey: No. I know Richard Dawkins is often accused as being rather extremist when he presents the case for not believing in a god, but I think a lot of people have reacted to his stridency saying he’s almost making his position religious. Personally, I can’t speak for other humanists and rationalists. If people want to teach children about the Christian philosophy, the basis of that faith and its origins as part of history or religious studies, I have no problem. I think kids should be exposed to the phenomena of faith. And if they want to go to Bible classes and want to become Christians, fine. But they should also recognize some of us don’t want to do that. I don’t care how religious you are as long as you leave me alone.

The Humanist: I’d like to turn to your conservation work. In your most recent book, Wildlife Wars, you discuss being appointed director of what became the Kenya Wildlife Service. The book closes with you briefly returning as director. How has the civil unrest in recent years impacted the conservation of national parks and wildlife?

Leakey: A lot of resources that might have been used to further conservation have been directed more to internal security. On another level, ethnic clashes and disturbances and the preoccupation with them has led to an economic slowdown in the country, which is very worrying. There are staggering increases in the number of people who are unemployed and who will never get jobs.

People who are desperate because they have no money to purchase food are inevitably people who, if there is something they can get their hands on without having to pay for it, will do so. Meat poaching has increased. That has had a big impact on conservation.

The Humanist: You’ve also talked about the corruption in government and national parks, which feeds into meat poaching and the ivory trade. How has this changed in recent years?

Leakey: Ivory once again has a very, very high value. People are tempted to get their hands on ivory to sell it on the black market. When you have high costs for kids to go to school and for medical fees, the temptation to join a group that will pay you to kill elephants is very real. But while it is poverty that drives the poaching, it is the greed of the buyer, the initial demand, that’s driving the growth of the supply.

The Humanist: What is the government doing to address poverty to make sure people don’t poach elephants and other animals?

Leakey: The 2030 plan is that everyone will have some income, that we will feed ourselves and export enough agriculture, have enough energy, have a lot of trade with others parts of Africa, and that some safety net will exist for the very poor. But the plan to get there and the integration of different sectors of the economy is very haphazard. Sadly, I think we have very poor leadership at the political level. One might say it’s almost as bad as the United States, where you have so much gridlock that nothing gets done. It’s a very shortsighted and rather stupid approach to the world’s affairs at this particular moment when the human population is growing so rapidly and the economic challenges of East-West, in a strict sense, are so different from what they were just fifteen years ago.

The Humanist: You’ve been active in Kenyan politics over several decades, including serving as a member of parliament. How have politics changed since President Kenyatta and President Moi’s one-party rule? Have things gotten better?

Leakey: In one sense they’ve gotten a lot better. We have a new constitution, which is still being enacted in terms of preparing legislative provisions for the constitution to be exercised. We have substantial improvements in basic freedoms. Our press is free without government interference. We have the right to say what we want, to assemble where we want, to demonstrate if we want, the right to criticize, which is all protected by our new constitution. There is a very vibrant young middle-income group who are using the social mediums to bring about increasing pressure to address certain issues. There have been huge advantages as a result of the constitution all over the place.

So the general trend in Kenyan government is positive, but corruption definitely exists and will continue to exist for some time. We have one of the stronger economic nations in Africa. With the majority of African countries seeking help from the European zone, the Chinese zone and other zones, African trade is still fairly small and that is the weakness of the future.

The Humanist: And what about political division based on ethnic lines?

Leakey: I think the lines are stronger today than I’ve seen in my lifetime. I think it’s because there are far more people without jobs and there is a tendency, if you’re in a position to employ people, to look to your own group within the nation. There is very little confidence in the possibility of natural justice and equity in a nation where you’ve got tribes that have a fairly good economic situation, in terms of potential to grow things and access to the ocean ports, and others who are on the periphery. Population growth is such that more people are falling into the poverty trap, and this can be exasperated by politicians who use the tribal argument: “We’re not getting the jobs because we’re in this area.”

The Humanist: Last question: Do you have any advice for aspiring scientists?

Leakey: The advice I’d give is that because the world has so many challenges coming up around climate change and scarcity of natural resources—challenges related to pathogens and microorganisms in terms of crop production, animal production, and human health—that a career in science is one of the best options you can go for today. We need such people who can be trained to find ways to avert what is otherwise going to be a downward spiral into a very poor lifestyle.

Ryan Shaffer is a historian and writer. He is currently a PhD candidate in the Department of History at Stony Brook University.