Astoria: John Jacob Astor and Thomas Jefferson’s Lost Pacific Empire

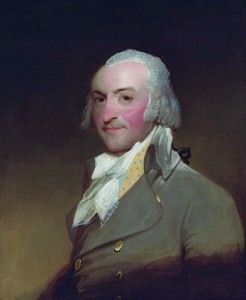

When the United States was very young—circa 1808—President Thomas Jefferson and the wealthy, successful businessman John Jacob Astor (fur trading, Manhattan real estate) had a joint brainstorm. In the aftermath of the Meriwether Lewis and William Clark expedition that explored the nation’s newly acquired Louisiana Purchase territory and the regions west of it, Astor saw the beguiling possibilities in establishing a trading center on the Pacific coast of the North American continent—virtually terra incognita at the time to everyone but the local Indian tribes. Astor was confident that his entrepôt would evolve into a mighty fur-trading enterprise linking the U.S., China, Russia, and the rest of Europe. The furs to be traded—sea otters (cherished by the Chinese elite), beaver, lynx, fox, bear—were known to exist in abundance in the far Western regions of North America. Controlling this enterprise, reaping the fabulous profits, would, of course, be Astor himself, who was born into humble circumstances in Germany but who became astonishingly successful after he immigrated to New York City.

Thomas Jefferson was a different kind of visionary. He believed that if Americans organized a settlement on the Pacific coast, a new nation, vibrantly democratic but separate from the United States, would eventually emerge from that initial outpost. Jefferson was convinced that this would be a good thing and urged Astor to proceed with his project. Astor was pleased with the moral support (although he probably would have undertaken the venture in any case) and brought his considerable canniness, meticulousness, and resources to the enterprise. Peter Stark’s Astoria skillfully describes those initial seductive objectives and the manifold disasters that ensued.

John Jacob Astor

Astor carefully made his plans and in 1810 dispatched two teams to install his trading emporium on the West Coast (it would be located at the mouth of the Columbia River, in present-day Oregon). One team went by sea, around the Cape of Good Hope at the southern end of South America; the other went by land and was supposed to follow Lewis and Clark’s route to the Pacific. The ship, the Tonquin, was captained by Jonathan Thorn, who had been “borrowed” from the American Navy. Thorn was a naval hero, but his virtues, whatever they were, didn’t translate well to his new job. An arrogant, humorless martinet, he made Captain Bligh look like Captain America. At least twice on the voyage, Thorn arranged for passengers who irked him to be killed. Needless to say, the civilians on board the Tonquin hated his guts. (A truism I’ve learned in my life: humanity evolves, science evolves, but loathsome bosses are forever.)

After Thorn finally reached his destination—it would be called Astoria by the survivors of the Tonquin—and unloaded his supplies and passengers, his ship sailed north to trade with various Indian tribes. Thorn was as incorrigible with them as with everyone else, but when he humiliated and insulted one tribe, they killed him and much of his crew. The vessel was blown up and sunk by some of the surviving Americans.

Wilson Price Hunt, who led the land expedition, was the temperamental opposite of Jonathan Thorn: an experienced fur trader in St. Louis, he was kind, considerate, and consensus-seeking. He was joined by several Scottish-Canadian fur trappers; French-Canadian voyageurs, expert at canoeing through the wilderness (Stark’s attempts to make these men colorful and folkloric characters fall flat, since the reader never gets a sense of them as individuals); clerks; two British botanists; and Indians picked up en route.

Despite Hunt’s decency, he too turned out to be a calamitous leader. A procrastinator with no experience in traversing wild terrain, he was victimized by his own tergiversating personality, but also bedeviled by brutal landscapes, hideous weather, and just plain rotten luck. When the Overland Party abandoned the Lewis and Clark route in order to avoid the hostile Blackfeet tribe—it veered south of that route—it had to negotiate ferocious snow storms, the Rockies, and turbulent rivers that even defeated the formidable voyageurs. Friendly Indian tribes often helped the party with food and advice; despite that, the expedition would be reduced at times to eating dogs and moccasin soles and drinking urine. Also, if the rumors were to be believed, some of the men, separated for a time from the main party, resorted to cannibalism. Hunt’s group finally reached Astoria and the Tonquin’s personnel in February of 1815, about two years after starting out. Not all of the original party made it.

The men who did reach Astoria went through the motions of building a rather shabby base camp and establishing a network of inland trading posts. But their hearts didn’t seem to be in their work; the hellish traveling and the environment in which Astoria was constructed—“the infinite gray coastline… backed by the thick, dark rain forest,” and sometimes-hostile Indians—appear to have purged Astor’s expeditionary members of energy and optimism. “Virtually every person involved, starting with Astor himself, grossly underestimated the psychological toll both journey and settlement would take on men and leaders alike” Stark writes. There was also another major problem. The British-Canadian North West Company, a rival of Astor’s in the efforts to dominate the fur trade in the West, was better prepared and much more professional than the Astorians. After war broke out between the United States and Britain in 1812, a delegation from the North West Company arrived at Astoria bearing an ultimatum: sell the post’s supply of furs and depart, or the Royal Navy would destroy the emporium and its inhabitants. In the absence of Hunt, his second-in-command, Duncan McDougall, who had once worked for the North West Company, “sold out John Jacob Astor’s West Coast enterprise and first American colony on the Pacific and all its goods—including some thousands of furs—for about thirty cents on the dollar.” Astor was livid, but there was nothing he could do.

Nevertheless, the failure of Astoria didn’t ultimately affect Astor’s wealth or his other businesses. In fact, when he died in 1848, he was the richest man in America. In 1846, the United States and Britain settled their Western border disputes by establishing a boundary at forty-nine degrees north, “the current U.S.-Canadian border today across the Northwest.” Depending on who’s doing the calculating, either sixty-one or sixty-five people died trying to carry out Astor’s grand, failed scheme.

Astoria is nicely done, thoroughly researched and well written. I respect Peter Stark for not demonizing Astor (though he was, it seems, not particularly ruthless for a powerful businessman, it probably was tempting to do so) and for not turning his book into another example of an irritating contemporary literary genre: the account of a historical journey that is more about the preening author’s experiences reenacting that journey than about history. Astoria doesn’t make its case for a link between Astor’s attempted empire-building and America’s modern focus on the Pacific Rim, but Stark does cogently discuss some other fraught areas of realpolitik: the influence of big business on government policies, the relationship between Europeans and Americans and Americans and Indians, and America’s Westward expansion. Surprisingly, the book doesn’t address another important subject: the ravaging of animal species by Astor and the North West Company. The tycoon and the company weren’t environmentalists, to put it mildly, and didn’t consider the repercussions of their policies; there is no indication in Astoria that these parties wanted to do anything but slaughter and take possession of as many desired beasts as possible.

Sometimes a book can raise suggestive points without meaning to. At one point, Stark describes the beleaguered Astorians this way: “Their sense of exposure deepened …. their camp was nothing but a tiny clearing between the vast wilderness of western North America’s mountains, forests, and rivers and the vastness of the Pacific …. It felt like the ends of the earth. Also woven between sea and forest was an elaborate and unseen network of Indian tribes … linked by a hidden communication network. It was another great unknown …. Should the Astorians need to flee, they had no one to run to, nowhere to hide …. Paranoia set in.” A sinister, dangerous environment; an unseen network of frighteningly alien cultures; a hidden, ominous communication network; and paranoia. Sounds like what’s unnerving the United States today.