Pathologies of Power Widespread tendency to defer to authority plays important role in the expansion of state power

“A tyranny,” Plato says in the Republic, “is the wretchedest form of government,” and “a tyrant grows worse from having power: he becomes and is of necessity more jealous, more faithless, more unjust, more friendless, more impious, than he was at first; he is the purveyor and cherisher of every sort of vice.”

This description of a tyranny and a tyrant may seem irrelevant to our situation in the United States today. After all, we live in a constitutional republic, in which the rights of the individual are protected by a written constitution and the rule of law. But how far are they actually protected in practice?

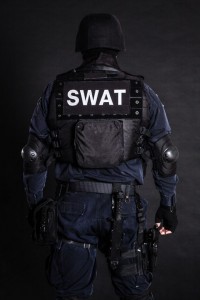

All around us we see the exercise of untrammeled power. SWAT teams in military gear break into people’s homes or businesses on the slightest suspicion. Police punch, kick, choke, arrest, strip search, and incarcerate citizens for minor infractions of the law—or no infractions at all. The very same behavior that by a citizen is a crime is seen as legitimate by a police officer, and our incarceration rate remains the highest in the developed world. As reported in Radley Balko’s 2013 book, Rise of the Warrior Cop, dozens of federal agencies—including the Departments of Education, Labor, and Agriculture—now have their own SWAT teams. Yet military equipment continues to flow to the police.

As the following examples show, what we have is not one tyrant but a many-headed beast that lives in the belly of the country, poised to strike at will, unconstrained by the rule of law.

Last year an op-ed in the Wall Street Journal reported on how zero-tolerance policies in schools have led to kids being charged with misdemeanors for “throwing an eraser, chewing gum,” or talking back. Bringing a small pocket knife to school can lead to a kid being charged with weapons possession, and making a gun gesture with the hands can lead to suspension. Kindergartners have been handcuffed for throwing tantrums, and three years ago a six-year-old in Georgia was cuffed and grilled for hours about the suspected theft of five dollars. Pretend violence or unruly behavior in little children is being met with real violence from police officers equipped with military-style weapons and handcuffs. Yet parents who handcuffed their children for worse behavior would be rightly seen as abusive.

Civil forfeiture laws allow police and prosecutors to “police for profit” by seizing property suspected of having been used for a crime—even if they never charge anyone with the crime. The property is “guilty” until its owner can prove its innocence, but without the means to hire a lawyer, the seized property is never recovered. In Ferguson, Missouri, and elsewhere, the police treat low-income communities as revenue streams, piling fine upon fine for minor offenses.

Comic by Milt Priggee, miltpriggee.com

The surveillance state violates our First and Fourth Amendment rights 24/7 by tracking our communications, and by inverting the requirement that our lives be kept private and the work of government officials made public. The directors of the National Security Agency and the Central Intelligence Agency suffer no consequences for lying to Congress about spying—they are above the law. By contrast, whistleblower Edward Snowden is charged with espionage and made an outlaw for exposing illegal spying by our own government. Again, we see that those who have the courage to “cast in [the tyrants’] … teeth what is being done,” as Plato puts it, end up being punished and silenced.

The beast’s power is exercised most brutally towards those who have the least power. Almost always, police departments exonerate cops who kill or brutalize unarmed civilians, but even when police officers are fired, their unions usually get them reinstated—with back pay. (See Conor Friedersdorf’s Atlantic report, December 2014.) Prosecutors typically refuse to bring charges, but even when they do, grand juries, under the control of the prosecutors, find no reason to indict the officers. Most disturbingly, when a grand jury does indict a police officer for murder and the case goes to trial, the jury often refuses to find the officer guilty, in spite of video evidence of the brutality.

Across the country, police have prevailed on cities for a special “law enforcement bill of rights”—in other words, exceptions to the criminal laws that apply to others. By playing up the danger they face, police gain sympathy from the public while, according to Balko’s book, refusing to divulge the number of yearly police shootings. Like tyrants, they feel they are not accountable to us. The so-called blue wall of silence further protects them in their illegal arrests and unprovoked violence by punishing fellow cops who have the courage to blow the whistle.

As Plato points out, tyrants cannot rule without purging the “valiant” and the “high-minded.” Anyone with virtue is a threat to them.

How did we get here? One answer is fear and ignorance. “Tough-on-crime” politicians and a cooperative media fan people’s fears of drug addicts, terrorists, school shooters, and sex predators, even though violent crime has been declining since 2004. In the general panic, courts and legislators erode the rights of criminal defendants and enhance the power of prosecutors and cops who enjoy “sovereign immunity” from prosecution for illegal use of force, false testimony, and perjury. Like sovereigns, they can “do no wrong.” And prosecutors are, in Sidney Powell’s words, “licensed to lie” (See her 2014 book, Licensed to Lie: Exposing Corruption in the Department of Justice, 2014). Even false testimony or repeated suppression of exculpatory evidence does not damage a prosecutor’s reputation. Police officers’ sense of self-righteousness, bolstered by TV shows that lionize cops as the good guys out to catch the bad guys by means fair or foul, is exhibited in their refusal to even apologize for killing or crippling innocent people in a SWAT raid. To paraphrase Plato, power makes a tyrant more faithless, more unjust, more impious, and “the purveyor and cherisher of every sort of vice.”

The widespread human tendency to defer to authority also plays an important role in the expansion of state power. The well-known experiments on obedience conducted by Stanley Milgram at Yale University in the early 1960s found that, in the “baseline” experiments, 65 percent of subjects obeyed the command to keep shocking the learner for every mistake all the way to 450 volts. Students who learn about the experiment often say that times have changed and Milgram would not get the same results now. Later replications of the experiments, however, suggest otherwise, as do real-life events like Abu Ghraib, the strip search phone call scam, and the ability of schoolyard bullies everywhere to find a loyal following.

The public’s unquestioning deference to authority goes hand-in-hand with contempt for the victims of police brutality, even non-violent victims of the War on Drugs, a contempt that has been encouraged by drug warriors who call drug users “enemies” or even “vermin.” The drug warrior par excellence, former Drug Czar William Bennett, even told middle-schoolers that turning their friends in for suspected drug use wasn’t “snitching” but rather “an act of true loyalty.” We don’t need totalitarianism to teach us that dehumanizing our victims makes it easier to victimize them, or that victimizing them makes it easier to dehumanize them, as Milgram’s obedient subjects found in the course of his experiments.

Unfortunately, power lust and unthinking deference to power are the most underrated vices. The fact that almost every new law restricting our freedom deepens political inequality by increasing the power of the state vis-à-vis the individual is almost universally ignored as moral outrage over one cause or another leads people to call for banning this or mandating that. The seven deadly sins of Christianity and popular culture don’t even mention power lust or unthinking deference to power. Even Plato, who rightly sees the tyrant’s soul as a den of vices, identifies not power lust as the tyrant’s fundamental vice, but sexual lust.

The obligation to disobey immoral authority is often discussed in political philosophy and military ethics, but major ethical theories say little, if anything, about power lust or unthinking deference to power as vices that play a major role in everyday life. Schools and religious institutions teach obedience to rules and to God, respectively, but not the danger of blind obedience or the lust for power in those with authority.

Teaching and internalizing this lesson, however, is one of the most important things we must do to restore our control over the state and, thus, over our lives.