Rescuing Memory: the Humanist Interview with Noam Chomsky

Photo by Sarah Silbiger

Photo by Sarah Silbiger JUST BEFORE TWELVE THIRTY on a recent spring afternoon, I found myself on the campus of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, in the building that houses both the linguistics and philosophy departments. A group of Japanese students, full of youthful excitement, were waiting outside Noam Chomsky’s eighth-floor office. They approached the door and read the name card on it. They took pictures—lots of pictures—with happy and surprised expressions, but then quickly turned serious. They paused for a brief moment of silence, which almost felt mystical, and then headed out.

At the age of eighty-seven, the renowned linguist, philosopher, historian, cognitive scientist, and critic Noam Chomsky maintains the same clarity found in any of his books, lectures, or television appearances dating back to the 1970s. While in a face-to-face conversation he might adopt an informal and humorous tone towards relevant topics, he is very much that same serious and detailed thinker we all recognize from the conferences and different interviews—one of those individuals history will remember for centuries.

Years after having met Chomsky at Princeton University and collaborating with him on the Spanish translation of a book (Ilusionistas, 2012), I was now interested in finding out the roots of his social and political thinking during our meeting. I started by remembering the many letters we’d exchanged for the better part of a decade. In one of the letters I had commented about how my son was adjusting to a society that was his but only by birth, noting that he spoke English with a slight Spanish accent. When Chomsky had a chance, he wrote me this:

When I was a boy, we were the only Jewish family in a terribly anti-Semitic neighborhood. Those streets weren’t any fun for us but our parents never found that out. In a way, you avoid telling your parents what happened to you during those days.

I reminded him of this in order to start a dialogue about that world and its universal implications. What follows is a conversation that went beyond what was initially planned.

Jorge Majfud: Before World War II, anti-Semitism and Nazism were much more common in the United States than Americans are willing to accept today. Henry Ford (awarded the Grand Cross of the German Eagle by the Nazi Government), General Motors, Alcoa, and Texaco are just a few examples of supportive U.S. business interests. And after the war, Jews faced serious and absurd obstacles in migrating as refugees while many Nazis were granted visas (through Mexico) to help develop NASA programs. What memories do you have of those times when you were a Jewish teenager?

Noam Chomsky: When I was growing up in the 1930s and ’40s anti-Semitism was rampant. It wasn’t like Nazi Germany but it was pretty serious—it was part of life. So, for example, when my father was able to buy a secondhand car in the late 1930s, and he took us to the countryside for a weekend, if we looked for a motel to stay in we had to see if it said “restricted” on it. “Restricted” meant no Jews. You didn’t have to say “no blacks,” which was something people took for granted. There was also a national policy, which as a child I didn’t know anything about. In 1924 the first major immigration law was passed. Before that, there was an Oriental Exclusion Act, but other than that, European immigrants like my parents were generally admitted in the early years of the twentieth century. But that ended in 1924 with an immigration law that was largely directed against Jews and Italians.

JM: Was it connected to the Red Scare?

Chomsky: Well, sort of—in the background. It was right after Woodrow Wilson’s first serious post-World War I repression, which deported thousands of people, effectively destroyed unions and independent press, and so on. Right after that, the anti-immigration law was passed that remained in place until the 1960s. And that was the reason why very few people fleeing the rise of fascism in Europe, especially in Germany, could get to the United States. And there were famous incidents like with the MS Saint Louis, which brought a lot of immigrants, mostly Jewish, from Europe. It reached Cuba, with people expecting to be admitted to the United States from there. But the administration of Franklin D. Roosevelt wouldn’t allow them in and they had to go back to Europe where many of them died in concentration camps.

JM: There were cases involving different countries as well.

Chomsky: It’s a lesser-known story, but the Japanese government (after the Russian-Nazi pact, which split Poland) did allow Polish Jews to come to Japan, with the expectation that they would then be sent to the United States. But they weren’t accepted, so they stayed in Japan. There’s an interesting book called The Fugu Plan, written by Marvin Tokayer and Mary Swartz, which describes the circumstances when European Jews came to Japan, a semi-feudal society.

After World War II there were many Jews who remained in refugee camps…President Harry F. Truman called for the Harrison Commission to investigate the situation in the camps and it was a pretty gloomy report. There were very few Jews admitted into the United States.

JM: These policies had many other lasting consequences.

Chomsky: Of course. The Zionist movement based in Palestine pretty much took over the camps and instituted the policy that every man and woman between the ages of seventeen and thirty-five should be directed to Palestine—not allowed to go to the West. A 1998 study was done in Hebrew by an Israeli scholar, Yosef Grodzinsky, and the English translation of the title is Good Human Material. That’s what they wanted sent to Palestine for colonization and for the eventual conflict that took place some years later. These policies were somewhat complementary to the U.S. policy of pressuring England to allow Jews to go to Palestine, but not allowing them here. The British politician Ernest Bevin was quite bitter about it, asking, “if you want to save the Jews, why send them to Palestine when you don’t admit them?” I suspect most likely that more Nazis came to America. I was a student at Harvard during the early 1950s. There was practically no Jewish faculty there.

JM: According to some articles, Franklin Roosevelt, when he was a member of the board at Harvard, felt there were too many Jews in the college.

Chomsky: There’s an interesting book about that called The Third Reich and the Ivory Tower, written by Stephen H. Norwood. It has a long discussion about Harvard, and indeed the school’s president, James Conant, did block Jewish faculty. He was the one who prevented European Jews from being admitted to the chemistry department—his field—and also had pretty good relations with the Nazis. When Nazi emissaries came to the United States, they were welcomed at Harvard.

JM: It’s something that was very common at the time, however today nobody seems willing to accept it.

Chomsky: In general, the attitude towards Nazi Germany was not that hostile, especially if you look at the U.S. State Department reports. In 1937 the State Department was describing Adolf Hitler as a “moderate” who was holding off the forces of the right and the left. In the Munich agreement in late 1938, Roosevelt sent his chief adviser Sumner Welles, who came back with a very supportive statement saying that Hitler was someone we could really do business with and so on. George Kennan is another extreme case. He was the American consul in Berlin until the war between Germany and the United States broke out in December 1941. And until then he was writing pretty supportive statements back stressing that we shouldn’t be so hard on the Nazis if they were doing something we didn’t agree with—basically repeating the idea that they were people we could do business with. The British had an even stronger business interest in Nazi Germany. And Benito Mussolini was greatly admired.

■

On racism of every color

JM: In addition to anti-Semitism and racism toward African Americans, there were other groups that suffered. For example, during the 1930s around half a million Mexican Americans were blamed for the Great Depression and deported in various ways. And most of them were U.S. citizens.

Chomsky: Well, there’s a strong nativist tradition—saying, “we have to protect ourselves”—that comes from the founding of the country. If you read Benjamin Franklin, who was one of the leading figures of the Enlightenment in the United States and the most distinguished representative of the movement here, he actually advised that the newly founded republic should block Germans and Swedes because they were too “swarthy”—dark.

JM: Why is that pattern of fear historically repeated?

Chomsky: There’s a strange myth of Anglo-Saxonism. When the University of Virginia was founded by Thomas Jefferson, for example, its law school offered the study of “Anglo-Saxon Law.” And that myth of Anglo-Saxonism carries right over into the early twentieth century. Every wave of immigrants who came were treated pretty badly, but when they all finally became integrated, all of us became Anglo-Saxons.

JM: Like the Irish. They were brutally persecuted, suffered violence because of their orange colored hair and their Catholicism, and then became “assimilated,” instead of being “integrated.”

Chomsky: The Irish were treated horribly, even here in Boston. For example, in the late nineteenth century they were treated pretty much like African Americans. You could find signs here in Boston in the restaurants saying “No dogs and Irish.” Finally they were accepted into society and became part of the political system, and there were Kennedys, and so on. But the same is true about other waves of immigrants, like the Jews in the 1950s. If you take a look at places like Harvard, it’s striking. In the early ,50s, I think there were a handful of Jewish professors, three or four. But by the 1960s, there were Jewish deans and administrators. In fact, one of the reasons why MIT became a great university was because they admitted Jews whereas Harvard did not.

JM: We can see changes in certain cases, but we can also see things that repeat themselves, such as now in the case of Mexicans and Muslims.

Chomsky: Yes, and Syrians. There is a horrible crisis there and the United States has admitted virtually none of the refugees. The most dramatic case is that of the Central Americans. Why are people fleeing Central America? It’s because of the atrocities the U.S. committed there. Take Boston, where there’s a fairly large Mayan population. These people are fleeing from the highlands of Guatemala, where there was virtual genocide in the early 1980s backed by Ronald Reagan. The region was devastated, and people are still fleeing to this day, yet they’re sent back. Just recently, the administration of Barack Obama, which has broken all sorts of records in regards to deportation, picked up a Guatemalan man living here. I think he had been living here for twenty-five years, had a family, a business, and so on. He had fled from the Mayan region and they picked him up and deported him. To me, that’s really sick.

JM: In the case of Guatemala, the story began in 1954 with the CIA military coup organized against the democratically elected President Jacobo Árbenz.

Chomsky: Yes, it basically began in 1954, and there were other awful atrocities in the late ’60s, but the worst happened in the ’80s. There was a really monstrous and almost literal genocide in the Mayan area, specifically under Ríos Montt. By now it has been recognized somewhat by Guatemalan society. In fact, Montt was under trial for some crimes. But the U.S. prohibits people from fleeing here. The Obama administration has pressured Mexico to keep them away from the Mexican border, so that they don’t succeed in reaching the United States. Pretty much the same thing Europeans have done to Turks and Syrians.

JM: Actually, under international law children should not, in principle, be detained when crossing a non-neighboring country’s border. The American Homeland Security Act of 2002 recognizes the same rights. However, this basic law has been broken many times.

Chomsky: A lot of countries break (or go against) the international law… There had been a free and open election in Haiti in the early 1990s and president Jean-Bertrand Aristide won, a populist priest. A few months later came the expected military coup—a very vicious military junta took over, of which the United States was passively supportive. Not openly, of course, but Haitians started to flee from the terror and were sent back and on towards Guantanamo Bay. Of course, that is against International Law. But the United States pretended that they were “economic refugees.”

■

The Spanish Civil War in the basis of Chomsky’s thinking

JM: Let’s go back very quickly to your contact with the Spanish anarchists. How important was the Spanish Civil War for your social thinking and activism?

Chomsky: Quite important. Actually, my first article—

JM: Which you wrote when you were eleven years old—

Chomsky: Ten, actually. It wasn’t about the anarchists; it was about the fall of Barcelona and the spread of fascism over Europe, which was frightening. But a couple of years later I became interested in the anarchist movement.

I had relatives in New York City who I stayed with. And in those days, the area from Union Square down Fourth Avenue had small bookstores, many of which were run by Spanish immigrants who’d fled after Franco’s victory. I spent time in them, and also in the offices of Freie Arbeiter Stimme (Free Worker’s Voice) with anarchists. I picked up a lot of material and talked to people, and it became a major influence. When I wrote about the Spanish Civil War many years later, I used documents that I picked up when I was a child, as a lot hadn’t been published (a lot more resources are available now). I also learned from reading the left-wing press about the Roosevelt administration’s indirect support for Francisco Franco, which was not well known, and still isn’t.

JM: Apparently Roosevelt regretted that decision but it was too late and the fact is that many other major corporations like ALCOA, GM, and Texaco were crucial for the defeat of the Second Republic—the only democratic experiment in Spain after centuries if we don’t consider the almost nonexistent First Republic during the nineteenth century. Many big companies collaborated with the Nazis and Franco.

Chomsky: It was reported in the left-wing press in the late 1930s that the Texas Company (Texaco), headed by the Nazi sympathizer Torkild Rieber, diverted its oil shipments from the Republic, with which it had contracts, to Franco. The State Department denied they knew about it but years later admitted it to be true. You can read it in history books now, but they often suppress the fact that the U.S. government tolerated it. It’s really remarkable because they claim that Roosevelt was impeded by the Neutrality Act. On the other hand, he bitterly condemned a Mexican businessman for sending several guns to the Republic. If you look back, oil was the one commodity that Franco could not receive from the Germans and the Italians, so that was quite significant.

JM: All of that sounds familiar.

Chomsky: During the terrorist regime in Haiti in the 1990s, the CIA, under the administration of Bill Clinton, was reporting to Congress that oil shipments had been blocked from entering Haiti. That was just a lie. I was there. You could see the oil terminals being built and the ships coming in. And it turned out that Clinton had authorized Texaco, the same company, to illegally ship oil to the military junta during a time when we were supposedly opposing the military junta and supporting democracy instead.

Same company, same story, but the press wouldn’t report it. They must have known. If you look at the Associated Press wires, there’s a constant flow of information coming in. At that time I happened to have direct access to AP wires. The day the marines landed in Haiti and restored Aristide there was a lot of excitement about the dedication to democracy and so on. But the day before the marines landed, when every journalist was looking at Haiti because it was assumed that something big was happening, the AP wires reported that the Clinton administration had authorized Texaco to ship oil illegally to the military junta. I wrote an article about the marine landing right away, but barely mentioned the oil, because my article would come out two months later and I assumed by then, “of course, everybody knows.” Nobody knew. There was a news report in the Wall Street Journal, in the petroleum journals, and in some small newspapers, but not in the mainstream press. And it was kind of a repeat of what happened in the late ’30s but this was under Clinton, mind you. These are some pretty ugly stories—not ancient history.

JM: Do you think the Spanish anarchists’ experience, had they not been destroyed by Franco, could be used as an example of a third position (to Stalinism, fascism, and Western capitalism)?

Chomsky: Well, the communists were mainly responsible for the destruction of the Spanish anarchists. Not just in Catalonia—the communist armies mainly destroyed the collectives elsewhere. The communists basically acted as the police force of the security system of the Republic and were very much opposed to the anarchists, partially because Stalin still hoped at that time to have some kind of pact with Western countries against Hitler. That, of course, failed and Stalin withdrew the support to the Republic. They even withdrew the Spanish gold reserves.

JM: The fourth largest in the world.

Chomsky: But before that, the anarchist movement was one of their main enemies… There’s an interesting question, whether the anarchists had alternatives. If they did tend to support the government that had been destroyed, what were the alternatives? There was actually a proposal by Camillo Berneri, an Italian anarchist who was in Spain at the time, which is not a crazy notion in my opinion. He opposed participation in government and was against the formation of an army, meaning a major army to fight Franco. He said they should resort to guerrilla war. Which has a history in Spain.

JM: Particularly at the beginning of the nineteenth century under the French occupation.

Chomsky: Under Napoleon Bonaparte’s occupation, yes. The same method could have been implemented during the Spanish Civil War, a guerrilla war against Franco’s invaders. But Berneri also advocated a political war. Franco’s army was mainly Moorish. They were recruiting people from Morocco to come to Spain. There was an uprising in Morocco at the time led by Abd el-Krim (whose tactics influenced Ho Chi Minh and Che Guevara) that sought independence for Morocco and Northern Africa. Berneri proposed that the anarchists should link up with the effort of Northern Africa to overthrow the Spanish government, carry out land reform, attract the base of the Moorish army, and see if they could undermine Franco’s army through political warfare in Northern Africa combined with guerrilla warfare in Spain. Historians laughed at that, but I don’t think they should have. This was the kind of war that might have succeeded in stopping Spanish fascism.

JM: There were few other successful cases of guerrilla resistance in the world.

Chomsky: There are cases—for example, the American Revolution. George Washington’s army lost just about every battle with the British, who had a much better army. The war was basically won by guerrilla forces that managed to undermine the British occupation. The American Revolution was a small part of a major world war going on between France and England, so the French intervened and that was a big factor, but the domestic contribution was basically guerrilla warfare. George Washington hated the guerrillas. He wanted to imitate the British red coat armies, fighting as gentlemen are supposed to fight. There are very interesting books about these events, for instance one by a very well-known American historian named William R. Polk called Violent Politics. It’s a record of what are basically guerrilla wars from the American Revolution right up through the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. He discusses the Spanish guerrilla war against Napoleon and other cases where the conflict turns into a political war, and the invader, who usually has overwhelming power, loses because they can’t fight the political war. Against this kind of background, I don’t think that the Berneri proposal was that absurd.

■

Photo by Sarah Silbiger

Our conversation continued informally on other topics, the most important being human intellectual capability. We touched on language, which has made possible communication, art, and liberation, while at the same time allows for deception and conscious oppression. The most serious current threats to human existence, according to Chomsky, are nuclear weapons and environmental catastrophe.

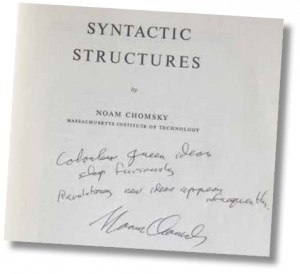

In my copy of his 1957 book Syntactic Structures (considered the most influential book of the twentieth century in the cognitive sciences and among the most important one hundred books ever published), Chomsky wrote for me his legendary sentence: “Colorless green ideas dream furiously.” Grammatically correct but semantically nonsensical, it’s the equivalent of E=mc2 for linguistics. Below this he added humorously: “Revolutionary new ideas appear infrequently.”

I gave him Memory of Fire by my dear friend Eduardo Galeano, who died last year, and Chomsky remembered him with affection. Right or wrong, both men have taught generations to never accept Stockholm syndrome, to never be accomplice to the crimes of arbitrary powers. Both men have taught us that memory and history aren’t always the same thing.

This interview, conducted on April 8, 2016, was edited for clarity and length.