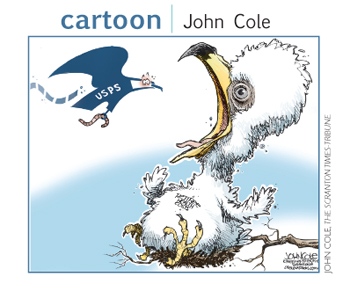

Going Anti-Postal What kind of nation won’t fund a Post Office?

There was a time not too long ago when mantles lined with Christmas cards were as ubiquitous as Christmas trees, when birthdays bestowed us with similar arrays, when the letter carrier would regularly visit our homes and drop off tangible graphic reminders that people loved us—that we were part of a community. Now our hundreds or thousands of Facebook “friends” hit a key and post to our pages. Our email inboxes might clog for a day or two with similar messages, laden with banner ads to market us happiness or merriment in accordance with what the date requires. Love, hate, and business, the pundits tell us, have migrated to email and social media, and hence that molluscan dinosaur, snail mail, is extinct.

But my disgust with the radical scheme to kill off the United States Postal Service has nothing to do with nostalgia or romanticism.

The Postal Service is not a mere delivery service, an outdated, inefficient alternative to FedEx or UPS. It’s a public service that every nation on earth, except for Somalia, maintains. In fact the United States joins Somalia as one of the only nations that doesn’t fund a postal system. We used to fund it, from the birth of our nation until Ronald Reagan’s presidency. It’s one of the only public services specifically addressed in the U.S. Constitution—right in Article One. Its genesis dates back to the Second Continental Congress, which appointed Benjamin Franklin as our first postmaster general.

The Postal Service is not a mere delivery service, an outdated, inefficient alternative to FedEx or UPS. It’s a public service that every nation on earth, except for Somalia, maintains. In fact the United States joins Somalia as one of the only nations that doesn’t fund a postal system. We used to fund it, from the birth of our nation until Ronald Reagan’s presidency. It’s one of the only public services specifically addressed in the U.S. Constitution—right in Article One. Its genesis dates back to the Second Continental Congress, which appointed Benjamin Franklin as our first postmaster general.

The original purpose of the Postal Service was not to deliver Christmas gifts or iPads but to deliver democracy. It was the conduit for political discussion and debate, tying a geographically dispersed population into a single, somewhat informed electorate. That’s why magazines and newspapers historically enjoyed a low, government-subsidized rate. The Founding Fathers realized that a large nation must communicate through media, and that privately funded media would skew the national debate toward the interests of the rich. Hence, they established the Postal Service and gave it a mandate to subsidize independent media with deeply discounted media mail rates. That’s why its formation was enshrined in the U.S. Constitution—for the same reason the Constitution guarantees freedom of speech and names journalism as the only profession that it specifically safeguards. A free press, including a means for disseminating that press, are paramount necessities for a democracy to function.

Today, one could argue that the Internet fills this function, rendering media mail obsolete—at least for the 60 percent of the population that have dedicated Internet connections. But there are a few major differences between the Postal Service and the Internet that undermine the latter’s ability to protect our democracy. First off, our Internet connection comes via a private portal. A handful of corporations monopolize ownership of this infrastructure and keep trying to exert control over what passes through it and at what speed, if at all. We must never forget this, and never take the Internet, or its temporal anarchy, for granted. We’ve already seen governments and compliant corporations around the world employ simple algorithms or outright filters to censor the Internet. The Postal Service’s media mail provides the redundancy that we need to guarantee a free press.

Also, unlike the cable and telephone monopolies that control our Internet connections, the Postal Service is legally required to provide uniform service, quality, and pricing to all Americans, regardless of where they live. By contrast, approximately 40 percent of the U.S. population doesn’t have dedicated Internet access, and about a quarter have no access at all to the so-called information superhighway. Those of us who do enjoy Internet access pay exorbitant rates, usually to maintain a subpar connection. One way to correct this would be to have the Postal Service run a government-subsidized Internet system, with the same guaranteed, universal access to affordable service that the postal system has historically provided. This would be in line with the founding fathers’ original charge to build mail highways, with the information superhighway being the modern equivalent of a road specifically constructed to facilitate communication. Also in line with the original intent, an affordable Internet with guaranteed net neutrality would protect future access to a free press. In a democracy, access to information should be a public service and a guaranteed right.

A postal Internet, however, would challenge entrenched corporate interests in the communication sector—entities that persistently rip us off and openly work to undermine our democracy. It’s no surprise that these communication corporations employ an army of lobbyists on the state and federal level, and are among the largest political contributors to pro-corporate politicians who carry their water in the halls of Congress. These are the same politicians who cut all subsidies to the U.S. Postal Service during the Reagan years, and now want to finally see it completely decimated.

Essentially, the war against the U.S. Postal Service is part of the same corporate-funded war against democracy that brands itself as a supposed libertarian battle against “big government.” The obvious contradiction in this rhetoric, however, is that you can’t have libertarianism while corporations are left standing. Remove the “we the people” checks on a plutocracy that government is supposed to provide, and we’re left at the mercy of unfettered corporatism, no matter how seductive the brand marketing is.

Here’s how the cards were stacked against the Postal Service. Congress passed a law mandating that the Postal Service, and only the Postal Service, pre-fund parts of its retirement system seventy-five years into the future. This mandate, which costs the Postal Service $5 billion per year, does not apply to any other government agency or private corporation. Take away this burden, and the Postal Service, amazingly, would be profitable. I say “amazingly,” because the Postal Service still provides media rates, as low as eleven cents, to deliver magazines and newspapers, and as low as seven cents to deliver nonprofit mail—all without the subsidy that similar agencies enjoy around the world, and that our Postal Service previously enjoyed for more than two centuries.

Even the regular first-class postage rate, which has gone up to forty-five cents, is remarkably cheap, considering that it includes pickup at your home and two-day delivery to almost the entire nation. Now think about UPS, FedEX, or DHL coming to your home to pick up anything for forty-five cents.

And it’s not just ordinary people who enjoy this service. As much as we hate junk mail, small businesses often survive by using bulk mailings to send parcels of up to 3.3 ounces for as little as fourteen cents. None of this is really lucrative business, which is why postal services around the world are subsidized. Ours is not. Add to this disadvantage the fact that corporate delivery entities like UPS and FedEx can cherry-pick services that are profitable to provide, much like charter schools cherry-pick problem-free students, and it becomes obvious how the deck is stacked against the survival of the Postal Service. It’s no coincidence that FedEx and UPS are two of the largest campaign contributors funding politicians working to kill the Postal Service altogether. Such a move would eliminate their primary barrier to unfettered profits, much like the absence of public service Internet has allowed communication companies to saddle us with the some of the most expensive and slowest internet connections in the developed world. I believe this is racketeering.

On December 5, 2011, the Postal Service, facing a predicable budget shortfall and the unwillingness of Congress to restore any funding to the agency, announced that it will close half of its mail processing centers and end next-day delivery of first-class mail. This would essentially initiate a downward spiral of service cuts followed by revenue drops, eventually leading to the total collapse of the Postal Service. This plan, temporarily on hold, is already being prematurely celebrated by the corporatist press. In a December 15 column in Forbes, Roger Kay looks forward to the day when the mail system is privatized. He writes, “I predict that the shift will be a net benefit to the overall system, despite the loss of jobs for more than a half-million postal workers. I hope they don’t go postal on me for saying so.”

The Postal Service has been able to hang on to life, thirty years after it lost all public funding while retaining all of its public service mandates, thanks only to its work force. These are, for the most part, highly educated workers who secured their jobs through a competitive process. They’ve kept this unfunded public service system running against all odds for decades. They not only handle mail but keep an eye on disabled shut-ins, senior citizens, and our homes, often being the first ones to notice if anything is amiss. Most chose this public service career because it offered secure employment with a guaranteed pension. The very precepts of this agreement are now in jeopardy because of a corrupt Congress beholden to corporate special interests that, in their unfettered greed, want to privatize and profitize all government services, no matter the cost to society, our democracy, or our freedoms.

I’d rather see these middle-class postal workers keep their jobs and continue to provide an essential communication service while Forbes’s Roger Kay queues up in a bread line, or, better yet, tries to find some honest work. Perhaps he’ll move to Somalia and experience the bliss of a postal-free society.

As the Postal Service creed goes, “Neither snow nor rain nor heat nor gloom of night stays these couriers from the swift completion of their appointed rounds.” Let’s hope they can also survive a Republican Congress.