Say What? The End of Net Neutrality and a Globalization Treaty Threaten Minority Speech

Few could argue that the Internet hasn’t revolutionized gay life. A generation came out on the web, and the freedom to launch a website adhering to one’s own standards of quality and authenticity has always gone along with that. That’s what both of us did, creating the social networks XY.com and Hornet. (In fact, equal Internet access may be how you found this article, and the Humanist for that matter.)

All this freedom could be coming to an end, unless the Federal Trade Commission and the Obama administration strongly change course to defend free speech. Otherwise, independent voices on the Internet could soon be entirely replaced by corporate websites or wealthy subsidiaries of AOL, Amazon, and Facebook; or silenced altogether.

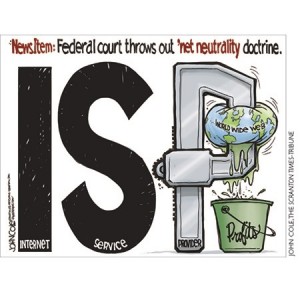

Absent strong government response, a cocktail of two repressive policy changes could push controversial sites off the Internet. The first is the loss of net neutrality.

In January the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia, in Verizon v. FCC, struck down the FCC’s Open Internet Order, which had required Internet service providers (ISPs) to carry all traffic, and carry it at the same speed, without extra charge to the provider. For example, under the stricken rule, TheHumanist.com would be delivered at the same speed as a well-funded site like the AOL-owned Huffington Post.

With the FCC rule stricken, each individual ISP is free to make deals with sites willing to pay, or might even excommunicate controversial sites it dislikes. Another scenario would see ISPs mirroring the practices of chain stores that replace brand names with in-store brands. For example, Comcast could replace TheHumanist.com with ComcastHumanist.com, and collect the advertising revenues from its copycat generic sites.

All of this is now legal, and while perhaps some ISPs won’t take advantage of the provisions, it’s likely some will—for profit, for political reasons, or both.

Of course, the FCC brought the net neutrality problem on itself—as noted in the DC Circuit decision—by classifying the Internet as an “information service” rather than a “common-carrier communication service” (like the telephone). The FCC could protect controversial speech today, simply by reclassifying the Internet as a communication service.

One might expect aggressive FCC and White House action to protect free speech. Think again. Instead, the White House is pushing the semisecret Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) treaty, a new set of globalization rules requiring Internet service providers here and across the Pacific Rim to deep-monitor and censor the Internet and report violations to international law enforcement.

Recent administration actions and judicial decisions have moved toward surveillance and increasing the profits of communications conglomerates, and away from promoting open access, internet innovation, fair-use journalism, or minority speech. That direction has raised bipartisan objections in Congress, but hasn’t yet made it to the floor.

So, why don’t the courts, Congress, the White House, and the FCC require strong due process on TPP prosecutions against controversial and small websites, and why doesn’t the FCC reclassify the Internet as a communications service, circumventing the court?

Follow communications companies’ lobbyists and campaign contributions, says Matt Wood, policy director of Freepress, the Washington, DC, nonprofit that fights for universal and affordable Internet access.“Remember that the ISPs have lobbyists on both sides of the aisle,” Wood says. “This is something of a bipartisan mistake.”

In a January 20, 2014, editorial, Wired magazine’s editorial board stated it more strongly: “The problem isn’t the ISPs, it’s the FCC.”

Faced with the circuit court decision, the FCC’s demurral, and the TPP treaty, the tech and website community is in an increasing panic. “We’re about to lose net neutrality and the Internet as we know it,” warned New America Foundation’s Marvin Ammori in a November 4, 2013, Wired opinion piece. “This means large phone and cable companies will be able to ‘shake down’ startups, requiring payment for reliable service.”

According to Ammori, “Once the court voids the nondiscrimination rule, AT&T, Verizon, and Comcast will be able to deliver some sites and services more quickly and reliably than others for any reason—whim, envy, ignorance, competition, vengeance, whatever. Or no reason at all.”

Of course, the ISPs deny that they would ever censor anyone—Verizon’s suit claims it simply seeks additional revenues to fund network growth. “The companies say: trust us, we are doing this for your own good,” Wood claims. But he doesn’t buy it. “‘Speed control’ means effectively blocking other sites,” he contends. “The difference between no blocking and discrimination is only a difference of degree, not kind. It’s not just about market power—it’s about whether you have to be in the ISP’s good graces.”

Does anyone think that none of the ISPs would censor controversial speech? “Verizon’s challenge could silence minority voices,” says Mike Ludwig, who has covered this issue for the site Truthout.org. “Without net neutrality protection, the companies could have the power to silence dissenting voices, or at least disfavor them with slower speeds to reach the public.”

And that is the problem with both “paid prioritization” and the TPP provisions: they provide both the means and the reasons to control speech—and history shows that given such power, some corporations and governments will inevitably use it to censor content they dislike.

In our experience in many countries across several decades, gay and “immoral” content is often the first to fall. There are many examples: Facebook treats gay content unequally right now, South Korean ISPs routinely ban gay content, and even the UK’s British Telecom blocked gay social networks in the early 1990s, putting several of them out of business.

But even without outright bias, the administrative burden of negotiating access fees with thousands of ISPs could be cost-prohibitive for many smaller sites. “Effectively, most ISPs are a monopoly,” says Wood. “In most parts of the country, you only have one choice.” An end to net neutrality, he foresees, could make the Internet more like radio—where only large corporate voices appear.

Returning to the Trans-Pacific Partnership, this proposed globalization agreement between eleven Pacific nations requires ISPs to deep-monitor all email and websites for “copyright infringement.” While infringement is ill-defined in the treaty—just the way corporate copyright holders want it—the TPP mandates each ISP set up an all-encompassing surveillance and censorship infrastructure that would make it much easier for ISPs to quickly and unilaterally charge or block users depending on what users do or say.

The TPP would require ISPs to read (a.k.a. deep-monitor) everyone’s email, scan all webpages, and set up a strict enforcement regime. And ISPs would have to set up a “six strikes” procedure that cancels websites and email addresses after six infringements. (Incidentally, the NSA’s involvement in the TPP’s strike determinations or surveillance is unknown.)

Unlike rich multinationals, smaller or minority voices might not have the funds to defend “strikes” or to set up expensive compliance regimes—setting aside the certainty that more conservative ISPs could simply silence unpleasant voices on the pretext of strikes. And, a copyright holder might be far likelier to prosecute a fair-use appearance on a gay website than an appearance on the Huffington Post.

The TPP requirements and infrastructure, combined with an end to net neutrality, would give ISPs both the profit motive and the means to rank, manage, or silence content. Why should we think that ISPs across the TPP’s eleven countries wouldn’t use these intrusive systems to censor inconvenient speech?

The Obama administration should know better. The FCC should reclassify the Internet as a common-carrier communications service, and Congress should deny the administration fast-track authority to pass the TPP. If the United States stands for anything, it stands for free speech. ![]()