Self-Management & Recovery Training A SMART Humanistic Approach to Addiction Recovery

Illustration by Anson Liaw

Illustration by Anson Liaw “The best antidotes to addiction are joy and competence—joy as the capacity to take pleasure in the people, activities, and things that are available to us; competence as the ability to master relevant parts of the environment and the confidence that our actions make a difference for ourselves and others.”

—Stanton Peele and Archie Brodsky,

Love and Addiction

IN ANCIENT TIMES there was a cruel and unusual capital punishment known as poena cullei (in Latin, “punishment of the sack”) that entailed placing the criminal in a sack along with a monkey, a dog, a rooster, and a viper, sewing the sack up, and then tossing it into the ocean. In many ways the pain, heartbreak, and devastation of being caught up in an addiction, or having someone you love caught up in an addiction, feels a lot like being sentenced to that fate.

Given the prevalence of addiction in society today, most people are aware that addiction has no social, racial, religious, or sexual boundaries. It afflicts the actor and the accountant, the doctor and the dockworker, both cisgender and transgender individuals, atheists and Amish, parents and children. And just as no human being is the same, no addiction experience is completely the same. Yet, according to Michael Werner, one of the founders of SMART Recovery (which stands for Self-Management and Recovery Training), there’s one thing people caught up in a substance addiction often have in common: the subconscious belief that if they quit using, they’ll die. This is what addiction feels like. As per the analogy of poena cullei—if someone with an addiction is bobbing in the ocean in a sack along with a rooster, a dog, a monkey, and a viper, instead of using the tools at his (or her) disposal to open the sack and set himself free, the addict truly believes the sting of the viper is what’s keeping him alive.

“Brian” was a troubled teen who used alcohol to stave off anxiety. As often happens, his anxiety increased over the years along with his drinking, until he found himself in a hospital bed confronting the realization that if he didn’t stop drinking, he’d die. For Brian, the fear of giving up alcohol, while scary, was less than the fear of what lay ahead if he didn’t. In addiction terms, this experience is known as “bottoming out.” Dr. Joe Gerstein, a physician, president of the Greater Boston Humanists, and another founder of SMART Recovery, describes the bottoming out experience as a secular conversion—a moment of clarity that changes everything. For Brian, who now regularly attends SMART Recovery meetings and has been sober for two and a half years, the tools and the support he found at SMART Recovery have helped him stay sober. But it was that moment, when he first realized the way he was living was “utterly unacceptable,” that really began to set him free.

The clarity that comes from bottoming out sometimes happens after being fired for drinking or taking illicit drugs on the job, being arrested—or worse, having killed or harmed someone while driving impaired. However, bottoming out often isn’t that dramatic or tragic. It comes as a gradual realization that the using is getting out of hand, and most people who realize they need to stop using simply stop. This is true for 75 percent of those who find themselves in this situation, according to the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. That lucky 75 percent do not make any declaration of powerlessness, nor do they enter rehab or get any help at all. They simply quit using and continue living their lives—happily, sadly, or however their life experiences happen to unfold.

In many ways, healing from addiction is similar to healing from a broken arm: some fractures are simple and can heal quite well on their own, while others are more complicated and need the attention of a physician. There is substantial evidence that the repeated use of drugs or alcohol damages the release and absorption of certain brain chemicals such as dopamine—the neurotransmitter responsible for the natural euphoria that follows sex or a good meal—and serotonin—dopamine’s Zen-like sister that brings on the feelings of satiation, calmness, and peace. But, just as a broken arm can heal naturally, the good news about drug-induced changes in the brain is that they too can be healed. With time and abstinence and hearty doses of the good life—music, exercise, love, creativity, and the joy of serving others—delightful dopamine and serene serotonin can be brought back into balance.

The bad news is that sometimes it can’t be brought back into balance without help because the urge to use comes from a combination of many factors, both environmental and chemical. So where can you go for help if you or someone you love is caught up in an addiction?

As with many medical and scientific issues, one finds conflicting research, advice, and dogmatic assertions that this way or that is the “right” or “wrong” way to proceed. “There is no single approach that is best for all individuals,” says SMART Recovery President Dr. Tom Horvath. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration reinforces this concept, stating that “there are multiple pathways to recovery.”

The most common recommendation for those needing help with recovery is likely to be Alcoholics Anonymous. AA—and its offshoots for gambling, overeating, sex, and drug addiction—is the oldest and largest program of its kind. It is famously a twelve-step program that has religious roots, although AA prefers to use the term “spiritual.”

The first step in AA is admitting to being powerless over the damaging substance or behavior, and acknowledging that because of this, one’s life has become unmanageable. The second step states a belief that a “power greater than ourselves could restore us to sanity.” In other words, if you’re in the sack in the ocean with the critters, your first step is to admit to being powerless and the second is to look to the divine for the strength to overcome your situation.

Obviously, the spiritual aspects of AA are likely to make humanists uncomfortable. Nevertheless, some humanists have made AA work for them by making secular changes to the twelve steps or replacing the concept of a “higher power” with the concept of a “higher self.” Basically, as Brian says, “If it works for you, do it.”

Fair enough—if it works, do it. There is no doubt that AA has worked for many people over the years but there is evidence to show that it’s not as effective as one would expect, or hope. A group of psychologists at the University of New Mexico led by Dr. William Miller have been evaluating every controlled study of alcoholism treatment they can find in order to determine success rates. While their surveys are ongoing, Miller and Reid K. Hester (a member of the SMART Recovery International council of advisors) have published three editions of their findings under the title, Handbook of Alcoholism Treatment Approaches: Effective Alternatives. Having evaluated forty-eight different addiction treatments, they found that Alcoholics Anonymous and twelve-step facilitation therapy rate among the least effective treatments available.

There is also some concern that the AA approach can be harmful. Stanton Peele, a radical pioneer in the addiction field, warns of the dangers of accepting the medical diagnosis of addiction as a progressive and debilitating disease over which one is powerless. In his writings Peele cites extensive research to back up his statements. If Peele is correct, believing that one is powerless over a progressive and debilitating disease can create a fatal attraction. According to Werner, labeling oneself as an addict and then continually reinforcing the notion that you are powerless over your addiction “can prove to be a self-fulfilling prophecy.”

Epictetus famously said: “Men are disturbed, not by things, but by the principles and notions which they form concerning things.” At its core, this is what SMART Recovery is all about; those who have gone through the program say that changing their way of thinking, rather than surrendering to their addiction, was key to their recovery.

SMART is a self-empowerment program. According to Gerstein, this means “that we don’t tell anyone what to do.” Employing various tools that have been shown to be effective, the program is also fluid. If a new discovery shows a better outcome, it is added as a tool for participants to consider trying, and if something isn’t effective, it’s put back on the shelf. If, like Brian, participants who tried AA first found something in the AA program that helped them, they’re encouraged to carry it along with them in their lives and in their recovery as another tool to use if they need it.

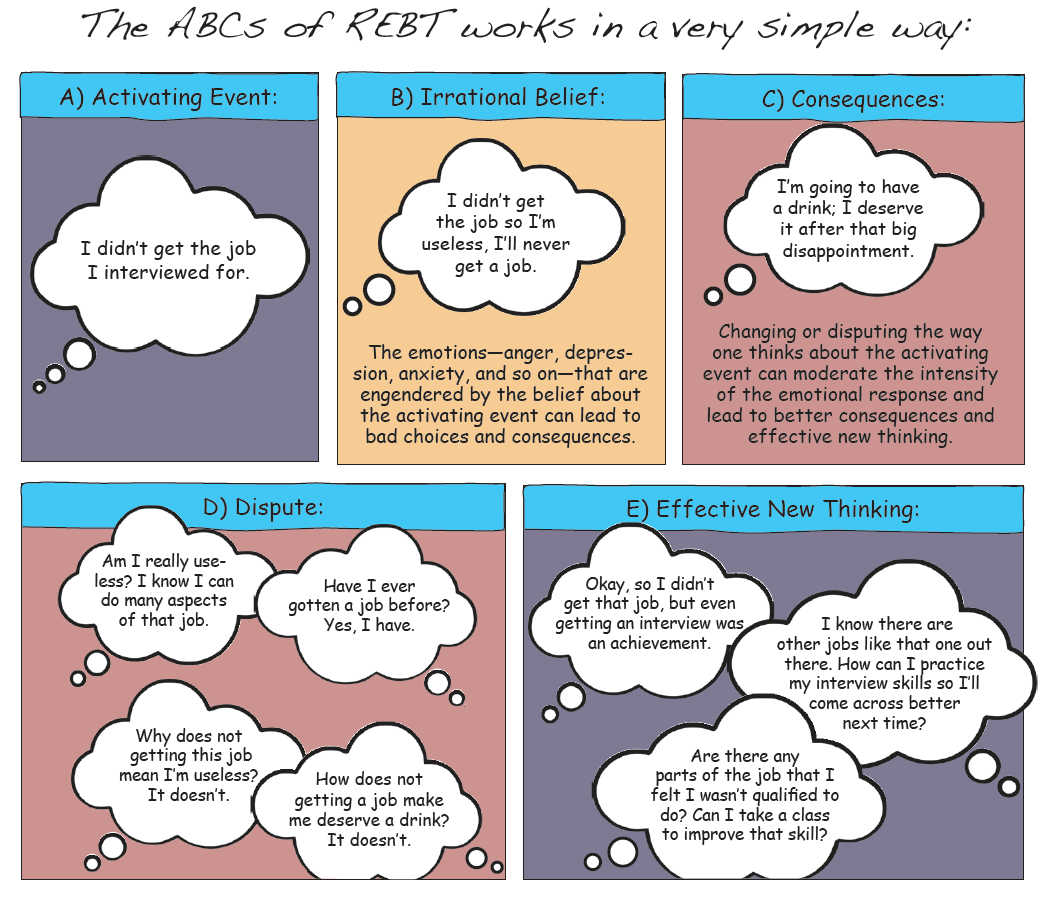

SMART does distinguish itself from AA in many ways. For one, participants are not considered powerless. “We equate the concept of powerlessness to walking around with a monkey on your back,” says Werner (former president of the American Humanist Association), who discourages participants from labeling themselves as addicts or alcoholics because “labels are sticky.” Many involved in SMART also prefer not to use the addiction-as-a-disease concept. “Addiction can be overcome with the power of our own minds, and the fact that there are mind/brain changes does not make it the same as a disease,” Werner says. Based on psychologist Albert Ellis’s Rational Emotive Behavioral Therapy (REBT), SMART’s four-point program focuses on enhancing the motivation to change, coping with urges, dealing with the problems of life effectively and rationally, and “lifestyle balance”—learning to balance immediate gratification with enduring satisfaction. These tools quickly help SMART participants focus on achieving positive goals. “When recovery feels good,” says Werner, “we are much more likely to continue.”

“Rob” began abusing substances when he was about fifteen years old. At first he did okay despite his substance use, but by the time he reached the age of thirty his drug and alcohol use had accelerated and he entered an in-patient AA facility for four months. Afterwards he attended a step-down program and then continued attending AA meetings. As an atheist, he was uncomfortable with the religious aspects of the program and always felt that going to an AA meeting was “like going to a church service.” Despite that, AA did work for him for many years.

Rob began drinking again after losing his job when the economy took a nosedive in 2008. Like Brian, Rob feels that he used alcohol to self-medicate his stress and anxiety. Although his life was unraveling again, he says he never felt completely powerless. He didn’t go back to smoking cigarettes, which he had quit many years before, and he made the conscious decision to never drink and drive. After nine months of heavy drinking, he realized he needed to quit when his wife left him and, like Brian, he landed in the hospital after drinking too much. This time, instead of going to AA, Rob found a SMART Recovery program that really clicked for him. He was relieved that he didn’t have to try to force himself to believe in a higher power. “SMART doesn’t look down on those who do believe in a higher power,” Rob notes. “If your belief is important to you and it helps with your recovery—that’s fine, too.”

In fact, as many as one third of SMART Recovery participants do have a spiritual belief, and it is neither encouraged nor discouraged. Rob likes having the support he gets from attending group meetings and being able to talk honestly with others. He feels that with AA, a slip back into using is often looked upon as a shameful thing, while at SMART, a slip is used as an opportunity to learn a new way to cope with urges.

SMART was one of the first programs to embrace the concept of harm reduction—the movement towards reducing the negative consequences of certain behaviors. And SMART does not require participants to quit using before starting the program. Participants can try to achieve moderation, although the overriding goal of SMART Recovery is abstinence and, even more importantly, reaching a place where participants don’t want to use again and are able to achieve lifestyle balance. Can that really ever happen? “Yes, it happens all the time at SMART,” says Gerstein.

Rob agrees. He’s now been sober for seven years and he and his wife have reconciled. He doesn’t want to drink again, even moderately, and he feels happy and satisfied without alcohol. “But,” he says, “it doesn’t happen overnight. You do have to be patient and keep working at it.”

The garage of tools taught by SMART help to hold up a mirror to show participants what’s happening in their minds. One example of a SMART Recovery tool is called the “ABCs of REBT.” For many, this is a very helpful way to clarify one’s thoughts and beliefs, and thereby one’s actions, and it reinforces SMART Recovery’s cornerstone principle: you control you. Abuse of alcohol or drugs stems from thinking incorrectly about how to handle setbacks in one’s life, called activating events.

SMART also offers hope regarding the four most common misconceptions about urges—that they are unbearable, that they compel you to use, that they won’t go away until you do use, and that they will drive you crazy. SMART says there is no evidence to support this belief and teaches participants not only that they can resist urges, but that the urges will get weaker over time.

“David” is a forty-six-year-old librarian who has a long history of heavy drug use, including heroin and what he calls an “insane amount” of the analgesics Dilaudid and Nubain, which he injected. An atheist, David says his recovery has been all about the “management of emotional chaos.” For him, using drugs was “amazing” and he did what he needed to do (“hustle, cheat, steal—things I’m not proud of”) to finance his drug use. He says he’s never met anyone for whom negative consequences—incarceration, threats, and so on—motivated them to stop. David’s recovery did, however, begin one day after a short stint in jail as he was standing in the freezing cold with no money and no way to get to his car. “I just can’t do another fucking day like this,” he recalls thinking.

While David is adamant that there’s no such thing as a miracle cure, he says the realization that he couldn’t do “this” anymore was a window of opportunity to engage in the possibility of a different life. He started attending SMART Recovery and working with the tools on a daily basis. David says that for him, managing emotional chaos meant learning as much as possible about addiction. Regarding urges and cravings, he was very encouraged to discover that, for him, they lasted between five and seven minutes. “So you feel bad for seven minutes—so what?” he says. Using SMART’s tools and drawing on his own history and intellectual resources has kept David clean for a year now, and for the first time in twenty years he’s optimistic about his life.

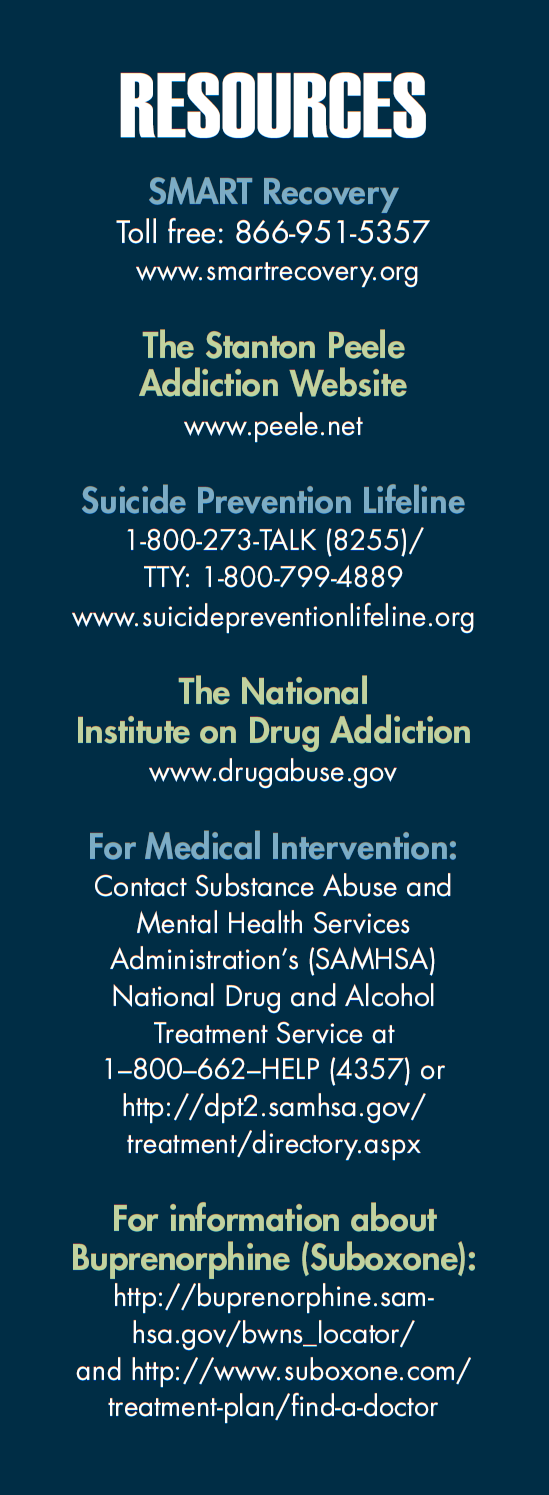

SMART Recovery was founded in 1994 by professionals and laypeople who had suffered from addiction. It was conceived as a nonprofit successor to Rational Recovery, a for-profit company owned by Jack Trimpey. Today, as SMART celebrates its twenty-second year as a nonprofit, there are over fourteen hundred weekly in-person meetings on six continents, and thirty weekly online meetings on SMART’s comprehensive and interactive website (see “Resources” on pg. 15). It’s website draws over 120,000 unique visitors per month and has 135,000 registrants. SMART’s online facilitator training program enrolls 150 people each month in it’s twenty-hour course, and about twelve new meetings per month are registered in the United States. The SMART Recovery program is used in communities, prisons, and hospitals, including McLean Hospital (Harvard Medical School’s major teaching hospital for mental health) and at the prestigious Massachusetts General Hospital.

“Sandra” says she lost ten years of her life to her addiction to Fioricet, a barbiturate that was first prescribed by her doctor for endometriosis. It was a secret addiction aided by the fact that she was able to acquire large amounts of Fioricet online. She said she was ashamed of her use and it was only when she was diagnosed with breast cancer that she made the conscious decision to “climb out of the rabbit hole of shame” and tell her doctors how much she was using. The most helpful tool in her recovery has been an understanding of how the drug use affected her brain chemistry. Sandra has a great sense of humor but she is also extremely honest about the difficulties associated with her recovery. She says she still feels lonely, depressed, and anxious but she knows she can’t treat those feelings with pills.

“Sandra” says she lost ten years of her life to her addiction to Fioricet, a barbiturate that was first prescribed by her doctor for endometriosis. It was a secret addiction aided by the fact that she was able to acquire large amounts of Fioricet online. She said she was ashamed of her use and it was only when she was diagnosed with breast cancer that she made the conscious decision to “climb out of the rabbit hole of shame” and tell her doctors how much she was using. The most helpful tool in her recovery has been an understanding of how the drug use affected her brain chemistry. Sandra has a great sense of humor but she is also extremely honest about the difficulties associated with her recovery. She says she still feels lonely, depressed, and anxious but she knows she can’t treat those feelings with pills.

One of the SMART Recovery tools—unconditional self-acceptance (USA)—was particularly helpful for Sandra, and also for “Gaye,” a woman who drank heavily, and secretly, for many years while raising her two sons. In the 1980s, when Gaye was about thirty-five, her drinking spiraled out of control and she was admitted to a hospital for detox, where a physician referred her to AA. She didn’t like attending AA meetings because she didn’t feel like she fit in. “I’ve never been a ‘church person,’” she says. She was sober for two years but when she tried to go back to drinking moderately, she soon found herself back to where she was before—drinking excessively, secretly, and often driving while intoxicated. She continued this way for a few years until, finally, on November 1, 2004, she “came clean” to her husband and told him exactly what was going on. She showed him all the places where she hid her bottles and together they ceremoniously poured the alcohol down the drain. Then they went onto their computers and found SMART Recovery. Gaye was able to attend meetings and get support from others at any time. Using the principle of unconditional self-acceptance helped Gaye to believe in herself and her ability to succeed.

Unconditional self-acceptance was famously parodied by now-U.S. Senator Al Franken (D-MN) as the character “Stuart Smalley” on Saturday Night Live, who would look at himself in the mirror and declare, “I’m good enough. I’m smart enough. And doggone it, people like me!” While very funny, the parody belittles the value of USA because its true value is less about people liking you and more about developing what Peele and Brodsky call part of the antidote to addiction: “the confidence that our actions make a difference for ourselves and others.”

With addiction, the stakes can be very high. Paul Rose, who lost his daughter Jana to a drug overdose in 2008, became a facilitator for SMART Recovery as a way to help others avoid the pain he and his family have experienced. He believes his daughter would still be alive today if she had had access to SMART Recovery tools and meetings. He writes on his SMART Recovery page: “My daughter Jana passed away because of a drug overdose. Her message to you is to get help. My beautiful daughter left behind her two daughters, her mother, and me. I ask you to please get help. I do not want you to suffer as we have.”

So, if you find yourself caught up in the poena cullei of addiction, start by reminding yourself that you are not powerless. Get the help and tools you need from whatever sources you can find that work for you, and open the sack of shame. Leave the vipers and monkeys and roosters and watchdogs of addiction behind. To paraphrase the words of Carl Rogers (founder of Humanistic Psychology), launch yourself fully into the stream of life.