Smart Thinking The Humanist Approach to Addiction and Our Heritage in Psychology

JUST ABOUT EVERY WEEK for the past twenty-five years you could (and still can) find me volunteering to help those with addictions by offering secular, scientifically based alternatives to Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) and its offshoots. I have seen incredible transformations by hundreds who have successfully overcome the slavery of addiction, but this work has also transformed me. It has renewed my faith in the potential for change in all of us, the inherent worth of every person, and my certainty that we are not powerless. I have seen those who even I had given up on suddenly “get it,” recover, and radically transform their lives. (I never give up on anyone anymore.) Traditional religious concepts of epiphany, redemption, rebirth, and salvation have secular meanings in these cases.

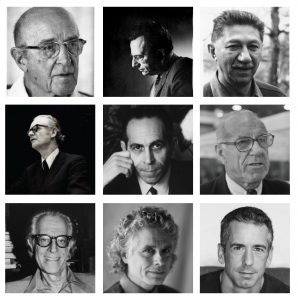

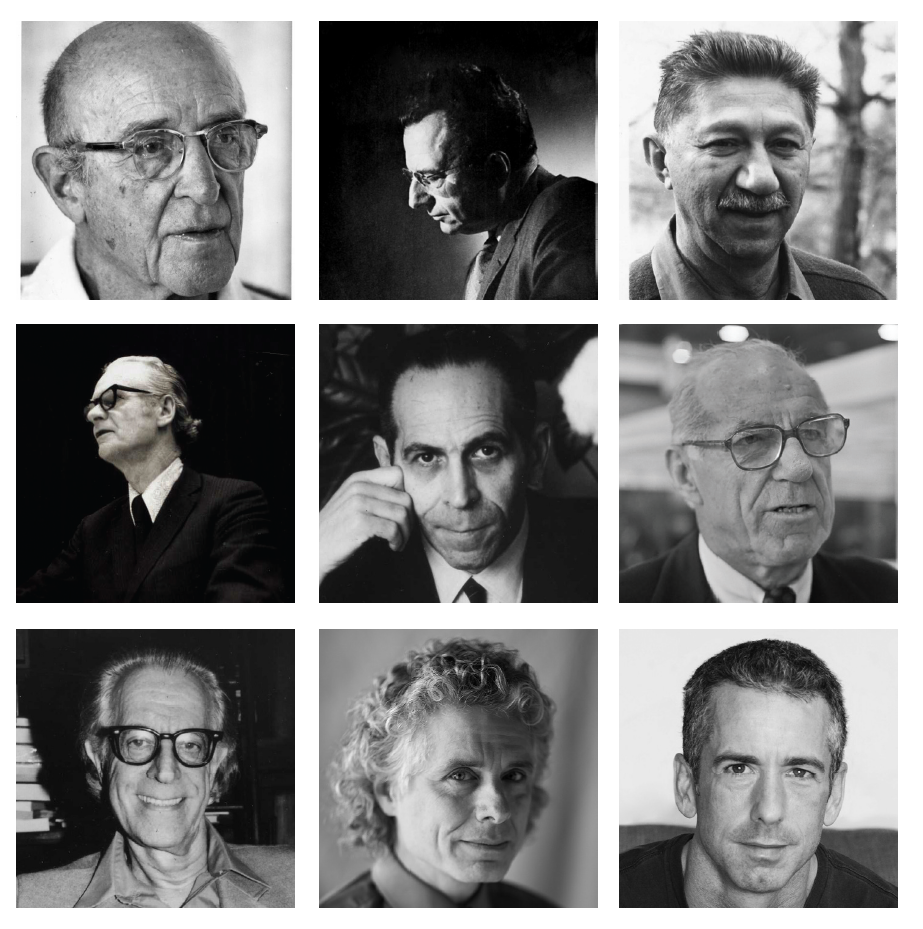

Psychology, not theology, is the heart of humanistic therapy, and humanists have a rich history within the field. Sigmund Freud sought a scientific description of behavior and saw that “religion is comparable to a childhood neurosis.” Since then, we find that virtually all the important figures in psychology were informed by their humanism. The following is a pantheon of prominent humanist forerunners in psychology, including the year they received the Humanist of the Year award from the American Humanist Association (AHA).

Carl Rogers (1964), the founder of humanistic psychology, said of life: “It involves the stretching and growing of becoming more and more of one’s potentialities. It involves the courage to be. It means launching oneself fully into the stream of life.”

Psychoanalyst and philosopher Eric Fromm (1966) saw freedom as an aspect of human nature that we either embrace or escape.

Abraham Maslow (1967), best known for creating his hierarchy of needs, asked what makes a healthy, flourishing human being.

Pediatrician Benjamin Spock (1968) studied psychoanalysis and called for more loving and less authoritarian methods in child rearing.

Albert Ellis (1971), founder of rational emotive behavioral therapy (REBT) and, indirectly, cognitive behavioral therapy, saw, as the Stoics did, that our ideas form much of our emotions, and our emotions direct our behavior. Learning to think rationally can then alleviate much of our harmful feelings and behaviors.

Behaviorist B. F. Skinner (1972) tried to understand behavior as resulting from reinforcing consequences.

Thomas Szasz (1973), a psychiatrist, warned of the dangers of coercive methods of control.

Experimental psychologist and linguist Steven Pinker (2006) has tackled many areas, including how we are a complex mixture of nature and nurture, and, more recently, how modernism is actually making the world safer and less violent.

And, finally, sex advice columnist and activist Dan Savage (2013) belongs on this list as he helps those troubled with sexual problems overcome myriad cultural limitations and pathologies.

Top (left to right): Carl Rogers, Eric Fromm, Abraham Maslow;

middle (left to right): B. F. Skinner, Thomas Szasz, Benjamin Spock;

bottom (left to right): Albert Ellis, Steven Pinker, and Dan Savage

Almost all of the above named Humanists of the Year were or are card-carrying AHA members and all have been transformative figures in the field of psychology. What they all have in common is a deep love of humanity, a trust in reason and science to guide our efforts, a passion for reducing emotional suffering, and a desire to enhance human welfare. They reject that we are mere toys of supernatural beings, or of fate, or of a fixed personality.

These are the threads that run through the successful substance abuse program known as SMART Recovery (Self-Management and Recovery Training) that I’ve been associated with for the past two decades. Honestly, I have no idea what people mean when they ask humanists where we find meaning and purpose when I see someone who hadn’t eaten solid food for three months (beer has a high caloric value) later remarry and succeed in a rewarding job. When I see a suburban soccer mom who was addicted to painkillers regain sobriety and her self-esteem. Or when I see a longtime heroin addict/alcoholic who’s been in and out of treatment centers all his life recover and wonder how he believed he was powerless for so many years. This is meaning that saturates my whole being.

This is why my experience as a volunteer in SMART Recovery has meant so much to me. All the great giants in psychology spoken of earlier paved the way by giving us the tools with which to change lives. They wanted to better the world and challenged worn-out ideas of who we are and what works. SMART Recovery was founded primarily by humanists who wanted to see real changes in the healing of broken lives. I can get lost in the esoteric and academic aspects of humanism, but each week I find that helping others with addictions allows me the opportunity to actually live my humanism, not just talk about it. As is said of addiction recovery, it allows me to walk the walk and not just talk the talk.

Photo credits: Rogers photo by Doug Land; Szasz photo by Lawrence Fried; Skinner, Fromm, Ellis, and Maslow photos provided by the American Humanist Association; “Benjamin McLane Spock (1976)” by Bert Verhoeff / Anefo – Nationaal Archief. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons; “Steven Pinker 2011” by Rebecca Goldstein Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons