Among the Truthers: A Journey Through America’s Growing Conspiracist Underground

“America,” Jonathan Kay writes in Among the Truthers, “has always been a land of cranks.” And his investigation of contemporary paranoid conspiracy theories and their precursors, and the people who cherish them, tends to prove his point. (Kay employs “conspiracism” and “conspiracists” as synonyms for, respectively, conspiracy theses and conspiracy mongers. Neither word is in any of my dictionaries, but Kay makes sensible use of them, so I’ll be using them too.) The individuals and dogmas uncovered by the author’s research are, inevitably, quite odd. But this book is strange—and disturbing—in ways that transcend that research.

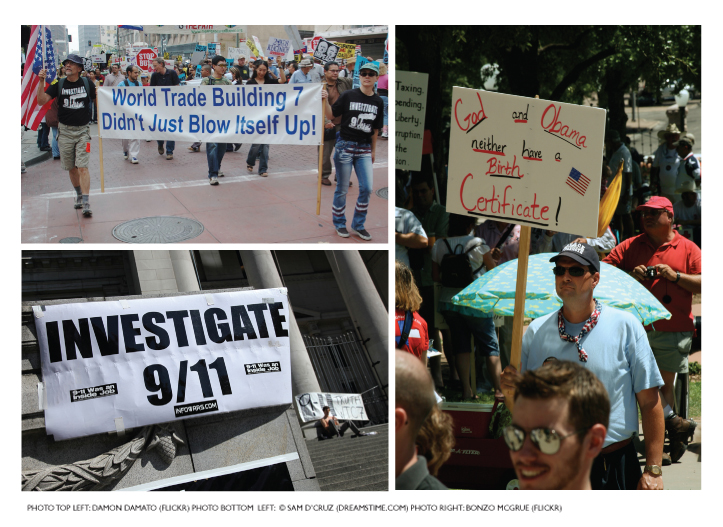

The Truthers of the book’s title believe that the conventional wisdom about the September 11, 2001, onslaughts on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon—what actually occurred and who was responsible—is at best wrong and at worst a deliberate hoax. There are diverse and (no surprise) sometimes contradictory elements of Truther “mythology” (as Kay calls it). Some of the theories are as follows: Bush administration neoconservatives secretly engineered the destruction on 9/11 in order to push the United States into a Middle East war; Israel was responsible for the 9/11 devastation; al-Qaeda is controlled by the Central Intelligence Agency; and the World Trade Center wasn’t demolished by aircraft, it was destroyed by bombs concealed in the skyscrapers. Perhaps the scariest aspect of this fatuousness is that, as Kay notes,

A 2006 Scripps Howard poll of over one thousand U.S. citizens found that 36 percent of Americans believe it was either “somewhat likely” or “very likely” that “federal officials either participated in the attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, or took no action to stop them.” About one-sixth of the respondents also agreed it was at least “somewhat likely” that “the collapse of the twin towers in New York was aided by explosives secretly planted in the two buildings.”

Unfortunately, the Truthers’ woozy doozies aren’t rare phenomena today. Kay doesn’t discuss my favorite conspiracist fable, the sham moon landing, but he provides a checklist of the many other screwy screeds circulating through our culture. To name a few: George W. Bush is a Nazi; Barack Obama isn’t an American citizen; the Federal Emergency Management Agency is a fascist enterprise; greenhouse-gas reduction strategies are pernicious plots; and, of course, that inevitable and vile standby, Holocaust denial.

As Kay conscientiously examines the roots of modern American conspiracism, he characterizes our current conspiracists as the heirs of three traditions: “religious apocalypticism, political populism, and rapid technological advancement.” I believe that populism is probably the most influential. During periods of economic turmoil (such as the one we’re experiencing in the United States right now), the destitute and dispossessed are inclined to perceive business and political elites and foreigners as the enemy, and project onto them hateful characteristics and malign aspirations. As the British psychiatrist and man of letters Anthony Storr remarked in his 1989 essay, “Why Human Beings Become Violent,” “I am convinced that there is a paranoid potential in most human beings which is easily mobilized in conditions of stress. This may be an individual experience, or the experience of a whole society.” (Kay complains that “surprisingly little research has been done on the psychology of conspiracy theorists.” But Storr, who died in 2001 and isn’t mentioned in Among the Truthers, wrote fairly often on the topic and brought erudition and insight to the task. Interested readers might want to look at the aforementioned essay, published in Storr’s Churchill’s Black Dog, Kafka’s Mice.)

Kay also makes a case that the repellent early-twentieth century anti-Semitic Russian forgery, the Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion, has contributed many fundamental components to the conspiracy fantasies thriving today. “In [modern] conspiracy theories,” Kay says, “the imagined evildoing cabal would come by many names—communist, globalist, neocon. But in most cases, it would exhibit the same five recurring traits that the Protocols fastened upon the Jewish elders in the shadow of World War I: singularity, evil, incumbency, greed, and hypercompetence.”

Complementing his scrutiny of conspiracism’s antecedents, Kay proposes some less sweeping, but allegedly significant dynamics that conceivably shape the psyche of the contemporary conspiracist. The least persuasive item cited is the midlife crisis. The most persuasive maintains that for conspiracists, their idée fixe is a kind of theology. “[C]onspiracy theories,” Kay asserts, “provide believers with many of the same psychological comforts as religion. Like many faiths, conspiracism supplies adherents with a Manichean moral structure, a satanic explanation for evil, and the promise of utopia.” I would only add that there seems little difference between the religious individual’s belief in miracles and the conspiracist’s conviction that his meretricious delusions truly describe and clarify reality.

Jonathan Kay is a good writer and an intrepid reporter and researcher. Unlike many of the doctrines he probes and some of the people he interviews, he is a long way from being uncouth and intemperate. Nevertheless, I have problems with this book. The author, for instance, is certain that conspiracism is a danger to the United States. “Conspiracy theories,” he says, “…are both a leading cause and a symptom of [America’s] intellectual and civic crisis. When a critical mass of educated people in a society lose their grip on the real world… it is a signal that the ordinary rules of rational intellectual inquiry are now treated as optional.” I’m not convinced that Kay is correct, because his major piece of evidence (about which he’s somewhat obsessive himself) seems to be the remarkable success enjoyed by Dan Brown’s conspiracy-suffused-but-harmless-hokum, The Da Vinci Code. Actually, Kay would have had a stronger argument (although not strong enough to persuade me) if he had tried to substantiate his contention with William Pierce’s abhorrent “novel”/conspiracism tract, The Turner Diaries. That book, which depicts the overthrow of the U.S. government by right-wing extremists, is revered by white supremacists and probably incited the Oklahoma City bomber, Timothy McVeigh. (On a lighter note, I suspect that the most popular conspiracism novel of all time is The Godfather.)

Reasonable people can disagree about Kay’s belief that conspiracism is undermining the United States. He is, however, unreasonable about some other points, and they ruined this book for me. Toward the end of Among the Truthers, Kay suggests that 9/11 “cemented the long process leading to Jews’ full-fledged ascension into the American [he means conservative American] establishment” and that criticism of Israel has become a left-wing, conspiracism-tinged phenomenon that is more likely than not inveterately hostile to that nation. “After decades of political correctness, it has become clear that the hypertolerant mantras of modern leftism supply no defense against the mind-warping effects of conspiracism,” he writes. “They simply deflect the conspiracist impulse to more fashionable targets such as Israel and the Jews that support it.” He also notes that “critics of Israel are perfectly correct that not all criticism of the Jewish state rises to the level of true anti-Semitism. But the boundary line is blurry and subjective.” I say that in all this Kay suggests, rather than demonstrates, because his declarations are more neoconservative wishful thinking than reflective of life as it actually is. To take the author’s last proposition first: Kay’s “boundary line” isn’t, in fact, that blurry and subjective. Those in the political center, or left of it, can deprecate certain Israeli government policies and still be dedicated to the wellbeing of Israel. To insist otherwise is tendentious nonsense.

As for “the Jews’ full-fledged ascension into the American establishment,” Kay’s principal proof seems to be that, “virtually every major Jewish group in the United States lined up foursquare behind the war in Iraq—thereby estranging many Jews from the wider peace movement in which they’d once taken such an active part.” But the most powerful Jewish organizations, which have, indeed, been politically conservative for a few decades, probably don’t represent the attitudes, political and otherwise, of most Jews in the United States, who, I think, have always been somewhat or fairly liberal. (A July 2011 Gallup poll found that 60 percent of American Jews support President Obama.) I worked for several years at one of the most influential Jewish defense agencies, and the only individuals who shaped its policies were the decidedly right-of-center bureaucrats in charge and the biggest contributors.

I was quite taken aback when I came across these observations by Kay, because up to then he’d been admirably evenhanded on left- and right-wing conspiracism. So I exercised some due diligence and discovered that he was a contributor to archconservative publications like Commentary, the Weekly Standard and the New York Post, and that his Wikipedia entry includes this statement: “Kay often endorses views regarded as conservative, particularly on the subject of Israel.”

I don’t condemn Kay for being a conservative. (Full unastounding disclosure: I’m a liberal.) What I do object to is that he’s not candid, in his comments on Israel, American Jews, et al., about his political principles and positions; rather, he appears to be conducting a kind of stealth offensive to promote his agenda. (I know—now I sound like a conspiracist.)

One final issue: Kay concludes Among the Truthers by lashing out at what he calls the “Church of Skepticism”—by which he means, in effect, atheists:

Man cannot survive on skepticism alone… society requires some creed or overarching national project that transcends mere intellect. When the appeal of traditional religion becomes weak, darker faiths assert themselves: including not only communism, fascism, tribalism, and strident nationalism, but also more faddish intellectual pathologies such as radical identity politics, anti-Americanism, and obsessive anti-Zionism.

As if America suffers from a lack of religiosity!

Kay seeks to clinch his case by quoting Voltaire: “If God did not exist, we would have to invent him.” The great French philosophe opined on many things; I’ll end with something else he said: “Doubt is not a pleasant condition, but certainty is absurd.”