Speaking Truth to Humanity (By George, I Think I Got It)

WHEN I WAS ASKED to speak in Denver at the American Humanist Association annual conference earlier this year, I was very flattered, and a little confused. I’m not an ardent atheist. I wasn’t raised within a religion or with a clear notion of God unless you count what my dad imbued in me after his many LSD trips. He went from believing in a “man in the sky with the beard,” to understanding that we are all connected to everything in the universe. He saw that because of our atomic structure, we are all just stardust.

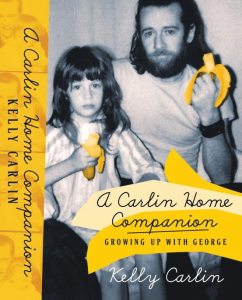

Kelly Carlin performs A Carlin Home Companion: Growing Up With George at the Falcon Theatre in Burbank, California. (Photo by Sherry Greczmiel)

With that kind of upbringing, I wasn’t compelled to define myself against any religious institution nor declare myself an atheist. I’ve never been a humanist on the front lines nor one who’s had to speak up and speak out in the face of religious oppression. And that is why I wasn’t sure if I belonged at a humanist conference. But then I realized that I may have something in common with all the folks in attendance: the difficulty in learning to speak our truth—especially our unpopular and dangerous truth—to the world. I’d like to share my journey around this issue with you.

My dad was George Carlin. One thing I’ve learned since his death is that some fans have assumptions about him, and about what it must have been like for me to grow up with him. One of the biggest assumptions people make, and it’s understandable, is that he taught me that speaking the truth—especially the dangerous and unpopular truth—is the most important thing you can do in your life. And he did teach me that. Sort of.

In the summer of 1972, when I was nine, my mom and I went on the road with my dad. Our first stop was Kent State University. Dad took me to the memorial for the four students who had been shot there two years earlier for speaking their truth to power by protesting against the Vietnam War. Right after that stop, we went to the outdoor Summerfest in Milwaukee so my dad could perform. During the concert he was arrested for using obscene language in public.

What did my nine-year-old self take away from all that? Speaking truth to power is dangerous. If you speak up and out, you get shot or arrested by the state. Not the greatest of ways to foster a sense of freedom of speech in a young mind.

But a week later, when I watched my dad step onto the stage at Carnegie Hall to a rambunctious and frenzied crowd that chanted his name over and over again, I was given a very different idea about speaking one’s truth. As I took in the electricity of that moment, my mind was filled with the idea that if you’re bold enough to speak authentically, you may become a god to thousands of people who hang on your every word. I was now thoroughly confused.

What I hadn’t realized was that I’d already learned my biggest lessons about truth by having to live with and manage my parent’s addictions. By the time I was six years old, I’d already witnessed too many arguments between them, and I’d become a rather anxious little girl. My dad worried about me and would ask, “You okay?” And I would always reply, “Fine.” I was afraid that if I told him how scared I was about their fighting, my world would come unhinged—daddy would leave, mommy would be mad, and I’d be left alone. Not speaking my truth had become equivalent to keeping me safe.

By the time I was ten, large amounts of cocaine and alcohol had unleashed chaos into our lives. I was now the family diplomat and routinely refereed their arguments. One time in particular, at three o’clock in the morning, my parents raged right outside my bedroom door. My dad couldn’t find his cocaine and accused my mom of stealing it. He’d hidden it in a book in our huge bookcase. The three of us began to tear apart the shelves book by book. When we finally found it, it was in Ram Dass’s Be Here Now. The next day at my best friend’s house, her mom asked how my parents were, and I said, “Fine. They’re fine.” I had learned to protect my family’s reputation by keeping my mouth shut.

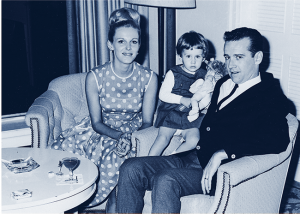

[caption id="attachment_13309" align="alignright" width="300"] Brenda, Kelly and George Carlin, circa 1965. (Photo used with permission by Kelly Carlin)[/caption]

Around that time, wanting a change of pace for the family, Dad took us on a Hawaiian vacation. Nothing changed; my parents fought incessantly. I finally broke down and became hysterical, at which point they realized how hard their arguing was on me. To keep the peace, I wrote out a UN-style peace treaty that they both signed. Twenty minutes later, Dad was in the bathroom snorting coke and Mom was headed for the bar. I learned a hard lesson that day: sometimes even if you do speak your truth, nothing really changes.

In 1975 my mom got sober, and two years later I started getting high. At age fourteen, I began to steal roaches from my dad’s stash and hang out with the stoner crowd. At sixteen, I began to hang out with a boy, the boy that all the girls wanted when he walked into a room. He had all the qualifications of a soulmate: every weekend we got high, watched Saturday Night Live, and ate Haagen-Dazs together. He was perfect—except for his sociopathic tendencies. He began to emotionally and physically abuse me.

Of course, I didn’t tell anyone. I’d see my dad in the hall, and he’d ask how I was and I’d say, “I’m fine.” Keeping up my reputation as the good girl who made smart choices and knew what she was doing was way more important than getting help. But a year later I had an ulcer, was sleeping all day, and missed a lot of school. Sometimes the pain from not sharing your truth becomes bigger than the fear of sharing it. I told my parents about the abuse. A few days later the boy showed up at my house and my dad threatened him with a baseball bat. (“You come near my daughter again, I’ll bash your fucking skull in!”) I guess sometimes when you tell your truth, things do change.

But at eighteen, I was a wreck. When my peers were looking forward to their future, I felt like I needed a nap. I went to UCLA for two weeks and then dropped out. Lost and confused, I got high and looked for even more chaos. What I found was a twenty-nine-year-old car mechanic who dealt cocaine, was on probation for manufacturing silencers of AR-15s, and was married but waiting for a divorce. He worshipped every aspect of me, spoon-fed me cocaine, and within three months was living in my bedroom in my parent’s house. He helped distract me from myself. But after a few years of feeling smothered by him and all his chaos, I decided I needed to finally grow up, so I married him. Yeah, I know. Crazy.

Instead of moving forward, I’d moved backwards. I found myself lost in a sea of denial, pretending for everyone around me how “fine” I was. I’d completely replicated the chaos of my childhood by marrying a man who knew only disorder. But I can see now how this actually solved a problem for me—I could avoid finding out who I was, what I really wanted, and what I was actually capable of by allowing myself to be distracted by him.

Seven years into the relationship, I was experiencing raging panic attacks, agoraphobia, and had no idea how to escape. I was twenty-five years old and knew I was wasting my life and my potential. At least now I finally knew that I was not fine. I knew I needed to leave, but I didn’t know how. Luckily, I didn’t have to know how. I just had to be willing to take one small step toward myself—my truth. I went back to UCLA. This time I thrived. During my third year, a writing professor wrote me a note: “Keep writing. You’ve got a lot to say to the world and a great way of saying it.” I told my dad and he said, “You’re on your way!” Yes, on my way! But where? I didn’t know.

And then one night I went to see a storyteller, Spaulding Gray. He’d made his fame with a film called Swimming to Cambodia. As I sat in the dark theater and watched him tell his story, everything changed for me. I suddenly knew exactly where I was heading.

Here was a man up on a stage revealing all his pain and confusion and neurosis, and it made me laugh. It made me cry. It freed me. And it made me feel like I finally belonged. Instead of being punished for telling his truth, Spaulding Gray was being celebrated for it. Instead of his truth ruining his reputation, it was building it. He was sharing the human condition, and it was healing all of us who listened. I wanted to do that.

Cut to eight years later. I was in my mid-thirties—the prime of my life—and married to a wonderful new man. I had a great job at a TV production company, stability, and hope. Even though I didn’t have the courage to tell my own stories yet, life was good. Then one day I came home from a business trip to find out that what the doctors thought were gallstones making my mother sick was actually liver cancer. She only had two months to live. I stayed home with her and my dad went on the road. No, he was not some heartless bastard. He just believed that he had no choice; he owed a lot of money to the IRS, had for about twenty years, and he couldn’t blow off his financial obligations. He didn’t want to leave but he felt he had to.

For me, it felt like the Carlins had taken a time machine back to 1974—Mom was dying, Dad was on the road, and I was pretending I was “fine.” I was unable to express my terror and sadness about my mom disappearing before my eyes, and unable to even feel rage towards my father for leaving me at home alone with her.

Five weeks later she was gone. I’d always imagined when my mom died I’d lose my mind. Instead, a strength poured into my body and a clarity came over my mind. I can only describe it as an awakening, a spiritual awakening. I’d never felt so connected to myself, life, the universe, and who I believed I truly was—it was a feeling of pure love.

When I spoke at my mom’s memorial, I talked about love (how it is the only thing that survives death), and I spoke about how one must be willing, as the great mythologist Joseph Campbell said, to live joyfully through the sorrows of the world. And as I looked out at the space that held everyone there—that unique space that is cracked open by death, where no one can hide—I felt such joy because I was so tired of hiding. I was so tired of being afraid to live my life as I was living it. I was so tired of not living my truth.

I had no idea how, where, or when, but I knew that I wanted the rest of my life to be about that very space. It was the first time I’d understood the word destiny. I’d had stirrings inside of wanting to be creative and make a dent in the world like my dad had, but I’d never felt a clarity about why. Now I did. I wanted to make a safe place for people’s humanity by sharing my experience.

After two years of deeply grieving the loss of my mother, I finally began to take my creative self seriously. I began to write out my life story—my funny, serious, and crazy life stories. I wrote a solo show that I hoped would give people permission to feel okay about their crazy lives too—just like Spaulding Gray had done for me. I felt like I was on a mission for truth. I felt it was time for me to finally express all that I had kept inside.

Once I had written and edited the script, I had it vetted by numerous people who I trusted would tell me if I was being an asshole, a victim, or an idiot. Then I confidently sent it to my dad. When I called him after five weeks of silence he said, “We have to talk…at your therapist’s office.”

Shit.

We sat down in the office and he said to me, “Kelly, you know I love you, but…” But. Oh, dear. And then came the very words I never wanted to hear him say: “I have to tell you, I feel deeply betrayed by this.”

He felt betrayed that I could reveal to strangers what was really going on deep inside of me—what was behind every “Hi, how are you?” and “Fine,” that had served as our mutual denial. He was also worried about the audience judging him as much as he judged himself for those dark drug days in the 1970s. Even though he’d spoken publicly about his addiction, there was something about me sharing my experience that made him feel vulnerable and ashamed. I had no desire to shame or blame, and I knew, by the way I had written about those years, I hadn’t. This is when I realized that even the great truth-teller, George Carlin, had difficulty with the truth of his own life.

He then told me that because he was an artist and I was an artist, he would never ask me to change a word of it. “But I do have to ask, why did I have to read your script to find out how upset you were with me when I left to go on the road when Mom was sick?” And there it was—the crux of the matter. This was the first time he’d heard about how upset I was with him leaving me alone with my mom those last five weeks. Telling him the truth about my feelings as I was having them two years earlier had been impossible. But quite frankly, he had never really encouraged me to share them either.

I looked up at him and said, “I don’t know. Maybe I thought I needed to be on your stage for you to finally hear me.” He looked at me, smiled a wry smile, and said, “Touché, kiddo.” We both realized in that moment how uncomfortable we’d been with the truth of our lives as we were living it.

I cancelled my six-week run; success without my dad’s approval was meaningless to me. But really, I was afraid that I’d lose my father forever if I went ahead with it. I only performed the show three times and my dad never showed up. But I have to say that the audience always loved him more in the end. I took my creative work and put it on a shelf. Just like when I was a child, I chose keeping my truth to myself in order to protect my relationship with my dad. And even though I no longer knew how or where I would fulfill my destiny, I still had my why—I wanted to make the world a safe place for everyone’s humanity.

Instead of going out into the world and onto a stage, I decided to go into myself and onto a master’s degree in psychology. At the age of thirty-eight, I enrolled at Pacifica Graduate Institute—a haven of Carl Jung and of Joseph Campbell, who taught me about the power of myth and story- telling. I learned there that the way we tell stories about ourselves and the world shapes our meaning and purpose.

In order to graduate, I had to spend a few years as an intern therapist. I was really good at it, as I’d been doing it since I was four years old in my own family. But I soon realized that I was helping everyone else manifest their dreams, and pretending I no longer had any. So I began to tell stories at a bunch of venues around Los Angeles, and really started to learn that craft. I had found my people. I discovered my voice. My dad even saw me perform once, remarking, “You know what you’re doing up there.” Encouraged by my progress, in 2006 I began to flesh out my memoir. If I couldn’t do a solo show, maybe I could write a book. I told my dad about it and he said, “Really? You know, real artists start with autobiographical material, but then they move on.” I didn’t know what to say to him. All I could think was—gee, Dad. I don’t think Richard Pryor ever moved on.

I put it on a shelf, once again choosing my relationship with my father over my need to express my truth. However it wasn’t out of blind habit this time, but because at this point I knew he was struggling with heart failure symptoms, and I didn’t want to add any stress to his life. Spending time with him was more important to me than telling my story. Dad was still my center of the universe. He was my sky god. He was the force behind everything.

In June of 2008, while in Hawaii officiating a wedding for a friend, I got a phone call from my husband Bob—my father was dead. That was June 22, 2008.

My father had always been the center of my universe, my sun, and once he left I knew it was time for me to become the center of mine. My sky god was dead. When I went to say goodbye to him before he was cremated, I wore a pendant with a beautiful drawing of a big orange sun on it. As I looked at him in the casket, I took off the necklace and placed it on his chest. I let him know that I loved him and would forever, but it was time for my life to revolve around my desires, visions, and dreams. I knew it’s what he’d always wanted for me. He never wanted me to give up my dreams for anyone or anything else.

Now that he’s been gone awhile, many of the lessons I learned from my childhood around speaking my truth—the dangerous and unpopular truth—have faded away. Slowly, I’ve gained more confidence and courage by finding a community of like-minded people, sharing my humanity in a number of forms and media, and learning from people who don’t always agree with me. It has helped me to open my mind and sometimes even change it.

Brenda, Kelly and George Carlin, circa 1965. (Photo used with permission by Kelly Carlin)[/caption]

Around that time, wanting a change of pace for the family, Dad took us on a Hawaiian vacation. Nothing changed; my parents fought incessantly. I finally broke down and became hysterical, at which point they realized how hard their arguing was on me. To keep the peace, I wrote out a UN-style peace treaty that they both signed. Twenty minutes later, Dad was in the bathroom snorting coke and Mom was headed for the bar. I learned a hard lesson that day: sometimes even if you do speak your truth, nothing really changes.

In 1975 my mom got sober, and two years later I started getting high. At age fourteen, I began to steal roaches from my dad’s stash and hang out with the stoner crowd. At sixteen, I began to hang out with a boy, the boy that all the girls wanted when he walked into a room. He had all the qualifications of a soulmate: every weekend we got high, watched Saturday Night Live, and ate Haagen-Dazs together. He was perfect—except for his sociopathic tendencies. He began to emotionally and physically abuse me.

Of course, I didn’t tell anyone. I’d see my dad in the hall, and he’d ask how I was and I’d say, “I’m fine.” Keeping up my reputation as the good girl who made smart choices and knew what she was doing was way more important than getting help. But a year later I had an ulcer, was sleeping all day, and missed a lot of school. Sometimes the pain from not sharing your truth becomes bigger than the fear of sharing it. I told my parents about the abuse. A few days later the boy showed up at my house and my dad threatened him with a baseball bat. (“You come near my daughter again, I’ll bash your fucking skull in!”) I guess sometimes when you tell your truth, things do change.

But at eighteen, I was a wreck. When my peers were looking forward to their future, I felt like I needed a nap. I went to UCLA for two weeks and then dropped out. Lost and confused, I got high and looked for even more chaos. What I found was a twenty-nine-year-old car mechanic who dealt cocaine, was on probation for manufacturing silencers of AR-15s, and was married but waiting for a divorce. He worshipped every aspect of me, spoon-fed me cocaine, and within three months was living in my bedroom in my parent’s house. He helped distract me from myself. But after a few years of feeling smothered by him and all his chaos, I decided I needed to finally grow up, so I married him. Yeah, I know. Crazy.

Instead of moving forward, I’d moved backwards. I found myself lost in a sea of denial, pretending for everyone around me how “fine” I was. I’d completely replicated the chaos of my childhood by marrying a man who knew only disorder. But I can see now how this actually solved a problem for me—I could avoid finding out who I was, what I really wanted, and what I was actually capable of by allowing myself to be distracted by him.

Seven years into the relationship, I was experiencing raging panic attacks, agoraphobia, and had no idea how to escape. I was twenty-five years old and knew I was wasting my life and my potential. At least now I finally knew that I was not fine. I knew I needed to leave, but I didn’t know how. Luckily, I didn’t have to know how. I just had to be willing to take one small step toward myself—my truth. I went back to UCLA. This time I thrived. During my third year, a writing professor wrote me a note: “Keep writing. You’ve got a lot to say to the world and a great way of saying it.” I told my dad and he said, “You’re on your way!” Yes, on my way! But where? I didn’t know.

And then one night I went to see a storyteller, Spaulding Gray. He’d made his fame with a film called Swimming to Cambodia. As I sat in the dark theater and watched him tell his story, everything changed for me. I suddenly knew exactly where I was heading.

Here was a man up on a stage revealing all his pain and confusion and neurosis, and it made me laugh. It made me cry. It freed me. And it made me feel like I finally belonged. Instead of being punished for telling his truth, Spaulding Gray was being celebrated for it. Instead of his truth ruining his reputation, it was building it. He was sharing the human condition, and it was healing all of us who listened. I wanted to do that.

Cut to eight years later. I was in my mid-thirties—the prime of my life—and married to a wonderful new man. I had a great job at a TV production company, stability, and hope. Even though I didn’t have the courage to tell my own stories yet, life was good. Then one day I came home from a business trip to find out that what the doctors thought were gallstones making my mother sick was actually liver cancer. She only had two months to live. I stayed home with her and my dad went on the road. No, he was not some heartless bastard. He just believed that he had no choice; he owed a lot of money to the IRS, had for about twenty years, and he couldn’t blow off his financial obligations. He didn’t want to leave but he felt he had to.

For me, it felt like the Carlins had taken a time machine back to 1974—Mom was dying, Dad was on the road, and I was pretending I was “fine.” I was unable to express my terror and sadness about my mom disappearing before my eyes, and unable to even feel rage towards my father for leaving me at home alone with her.

Five weeks later she was gone. I’d always imagined when my mom died I’d lose my mind. Instead, a strength poured into my body and a clarity came over my mind. I can only describe it as an awakening, a spiritual awakening. I’d never felt so connected to myself, life, the universe, and who I believed I truly was—it was a feeling of pure love.

When I spoke at my mom’s memorial, I talked about love (how it is the only thing that survives death), and I spoke about how one must be willing, as the great mythologist Joseph Campbell said, to live joyfully through the sorrows of the world. And as I looked out at the space that held everyone there—that unique space that is cracked open by death, where no one can hide—I felt such joy because I was so tired of hiding. I was so tired of being afraid to live my life as I was living it. I was so tired of not living my truth.

I had no idea how, where, or when, but I knew that I wanted the rest of my life to be about that very space. It was the first time I’d understood the word destiny. I’d had stirrings inside of wanting to be creative and make a dent in the world like my dad had, but I’d never felt a clarity about why. Now I did. I wanted to make a safe place for people’s humanity by sharing my experience.

After two years of deeply grieving the loss of my mother, I finally began to take my creative self seriously. I began to write out my life story—my funny, serious, and crazy life stories. I wrote a solo show that I hoped would give people permission to feel okay about their crazy lives too—just like Spaulding Gray had done for me. I felt like I was on a mission for truth. I felt it was time for me to finally express all that I had kept inside.

Once I had written and edited the script, I had it vetted by numerous people who I trusted would tell me if I was being an asshole, a victim, or an idiot. Then I confidently sent it to my dad. When I called him after five weeks of silence he said, “We have to talk…at your therapist’s office.”

Shit.

We sat down in the office and he said to me, “Kelly, you know I love you, but…” But. Oh, dear. And then came the very words I never wanted to hear him say: “I have to tell you, I feel deeply betrayed by this.”

He felt betrayed that I could reveal to strangers what was really going on deep inside of me—what was behind every “Hi, how are you?” and “Fine,” that had served as our mutual denial. He was also worried about the audience judging him as much as he judged himself for those dark drug days in the 1970s. Even though he’d spoken publicly about his addiction, there was something about me sharing my experience that made him feel vulnerable and ashamed. I had no desire to shame or blame, and I knew, by the way I had written about those years, I hadn’t. This is when I realized that even the great truth-teller, George Carlin, had difficulty with the truth of his own life.

He then told me that because he was an artist and I was an artist, he would never ask me to change a word of it. “But I do have to ask, why did I have to read your script to find out how upset you were with me when I left to go on the road when Mom was sick?” And there it was—the crux of the matter. This was the first time he’d heard about how upset I was with him leaving me alone with my mom those last five weeks. Telling him the truth about my feelings as I was having them two years earlier had been impossible. But quite frankly, he had never really encouraged me to share them either.

I looked up at him and said, “I don’t know. Maybe I thought I needed to be on your stage for you to finally hear me.” He looked at me, smiled a wry smile, and said, “Touché, kiddo.” We both realized in that moment how uncomfortable we’d been with the truth of our lives as we were living it.

I cancelled my six-week run; success without my dad’s approval was meaningless to me. But really, I was afraid that I’d lose my father forever if I went ahead with it. I only performed the show three times and my dad never showed up. But I have to say that the audience always loved him more in the end. I took my creative work and put it on a shelf. Just like when I was a child, I chose keeping my truth to myself in order to protect my relationship with my dad. And even though I no longer knew how or where I would fulfill my destiny, I still had my why—I wanted to make the world a safe place for everyone’s humanity.

Instead of going out into the world and onto a stage, I decided to go into myself and onto a master’s degree in psychology. At the age of thirty-eight, I enrolled at Pacifica Graduate Institute—a haven of Carl Jung and of Joseph Campbell, who taught me about the power of myth and story- telling. I learned there that the way we tell stories about ourselves and the world shapes our meaning and purpose.

In order to graduate, I had to spend a few years as an intern therapist. I was really good at it, as I’d been doing it since I was four years old in my own family. But I soon realized that I was helping everyone else manifest their dreams, and pretending I no longer had any. So I began to tell stories at a bunch of venues around Los Angeles, and really started to learn that craft. I had found my people. I discovered my voice. My dad even saw me perform once, remarking, “You know what you’re doing up there.” Encouraged by my progress, in 2006 I began to flesh out my memoir. If I couldn’t do a solo show, maybe I could write a book. I told my dad about it and he said, “Really? You know, real artists start with autobiographical material, but then they move on.” I didn’t know what to say to him. All I could think was—gee, Dad. I don’t think Richard Pryor ever moved on.

I put it on a shelf, once again choosing my relationship with my father over my need to express my truth. However it wasn’t out of blind habit this time, but because at this point I knew he was struggling with heart failure symptoms, and I didn’t want to add any stress to his life. Spending time with him was more important to me than telling my story. Dad was still my center of the universe. He was my sky god. He was the force behind everything.

In June of 2008, while in Hawaii officiating a wedding for a friend, I got a phone call from my husband Bob—my father was dead. That was June 22, 2008.

My father had always been the center of my universe, my sun, and once he left I knew it was time for me to become the center of mine. My sky god was dead. When I went to say goodbye to him before he was cremated, I wore a pendant with a beautiful drawing of a big orange sun on it. As I looked at him in the casket, I took off the necklace and placed it on his chest. I let him know that I loved him and would forever, but it was time for my life to revolve around my desires, visions, and dreams. I knew it’s what he’d always wanted for me. He never wanted me to give up my dreams for anyone or anything else.

Now that he’s been gone awhile, many of the lessons I learned from my childhood around speaking my truth—the dangerous and unpopular truth—have faded away. Slowly, I’ve gained more confidence and courage by finding a community of like-minded people, sharing my humanity in a number of forms and media, and learning from people who don’t always agree with me. It has helped me to open my mind and sometimes even change it.

These last four years I’ve had the privilege of sharing my and my family’s story in front of thousands of people. I have been touring and performing my solo show, “A Carlin Home Companion,” in many cities, and my memoir of the same name is being published in September. My story, at times, may have been the difficult and unpopular truth to my father, but not his fans. Over and over again audiences have let me know that their hero, George Carlin, is even more important to them now because he has become more human to them.

More importantly, I feel very grateful that in sharing my vulnerability and humanity, it has inspired others to take creative leaps or to go home and have difficult conversations with their families. All those decades of pain, confusion, and denial have been transformed into courage for others.

I have learned that discovering and telling your story does three very important things:

These last four years I’ve had the privilege of sharing my and my family’s story in front of thousands of people. I have been touring and performing my solo show, “A Carlin Home Companion,” in many cities, and my memoir of the same name is being published in September. My story, at times, may have been the difficult and unpopular truth to my father, but not his fans. Over and over again audiences have let me know that their hero, George Carlin, is even more important to them now because he has become more human to them.

More importantly, I feel very grateful that in sharing my vulnerability and humanity, it has inspired others to take creative leaps or to go home and have difficult conversations with their families. All those decades of pain, confusion, and denial have been transformed into courage for others.

I have learned that discovering and telling your story does three very important things:

- It helps you create order out of chaos. Your life begins to make sense and have some meaning.

- It allows your fellow humans to feel less alone, which makes the world smaller and more connected in the end.

- Speaking the dangerous and unpopular truth expands the edge of human consciousness.