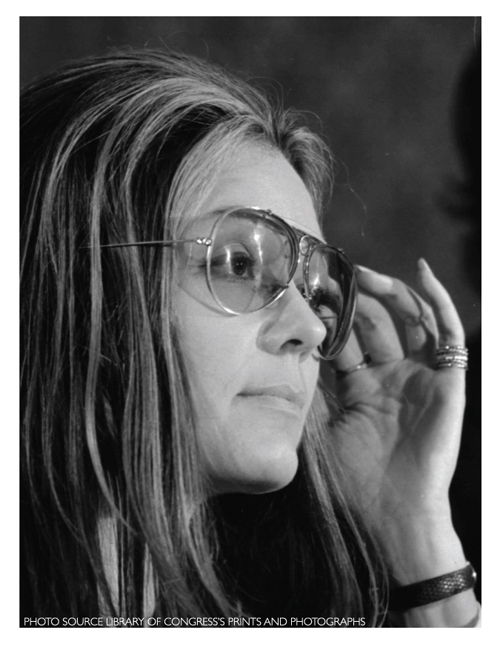

The Humanist Interview with Gloria Steinem

2012 Humanist of the Year Gloria Steinem sat down with the Humanist magazine at the 71st Annual Conference of the American Humanist Association, held June 7-10, 2012, in New Orleans. The following is an adapted version of that interview recorded on Friday, June 7. Previously solicited questions from leading secular women writers are noted herein. Steinem’s speech in acceptance of the Humanist of the Year award will be published in the November/December issue.

The Humanist: You’re being honored with the 2012 Humanist of the Year award. What led to you accepting this award from the American Humanist Association? Do you feel that your writing and activism as a feminist intersects with humanism?

Gloria Steinem: I always thought that “humanist” was a good word long before I understood that anyone thought it was a bad word. It seems to me that it means you believe in the great potential and the best of human beings, so I didn’t have to overcome anything to accept this award; it seemed an unmitigated honor. And since the ultra-right wing has tried so hard to make it a bad word— “humanist” has been demonized in much the same way that the word “feminist” has—it seemed especially important to identify as humanist and support humanist groups. This is the only national group I know of, but I run into local ones, too.

The Humanist: So let’s talk a little about women in secularism. I attended the first-ever Women in Secularism conference in May, and I’m wondering if it would surprise you to learn that there are problems with sexist behavior within the secular movement, including in online forums and at conferences.

Steinem: No, it doesn’t surprise me to learn that there is bias and sexism everywhere, just like there are problems of racism and homophobia stemming from the whole notion that we’re arranged in a hierarchy, that we’re ranked rather than linked. I think we’ve learned that we have to contend with these divisions everywhere.

Steinem: No, it doesn’t surprise me to learn that there is bias and sexism everywhere, just like there are problems of racism and homophobia stemming from the whole notion that we’re arranged in a hierarchy, that we’re ranked rather than linked. I think we’ve learned that we have to contend with these divisions everywhere.

There might have been more surprise, say, in the 1960s and ’70s when people were active in the antiwar movement or in the Civil Rights movement, only to discover that women sometimes had the same kinds of conventional positions there. But I think there’s a much deeper understanding now of how widespread patriarchy is, on the one hand, and that it didn’t always exist, on the other.

The Humanist: So, if humanists and secularists consider themselves enlightened individuals—reasonable, progressive, and so forth—shouldn’t we hold these men up to a higher standard in terms of sexist behavior?

Steinem: Yes. But, it’s not only holding humanist men up to a higher standard, it’s saying you can’t win unless you’re a feminist. Because the patterns that are normalized in the family—the whole idea that some people cook and some people eat, that some listen and others talk, and even that some people control others in very economic or even violent ways—that kind of hierarchy is what makes us vulnerable to believing in class hierarchy, to believing in racial hierarchy, and so on.

The Humanist: Can men be seen not just as participants, but as effective leaders in the feminist movement?

Steinem: Yes. I definitely think men can be leaders. I see an analogy in the case of what helped me think about racism, which was to find parallels with sexism. In other words, I don’t think I was such a great ally until I got mad on my own behalf. Until I thought, wait a minute, how dare anybody tell me who my friends are or where I should live. That only happened after living in India and suddenly coming home and seeing how race-conscious we were, and how restricted I was, in a different way, as a white person.

The men I’ve met who were the best allies of feminism are those who see their stake in it; who see that they themselves are being limited by a culture that deprives men of human qualities deemed feminine, which are actually just the qualities necessary to raise kids—empathy and attention to detail and patience. Men have those qualities too but they’re not encouraged to develop them. And so they miss out on raising their kids, and they actually shorten their own lives. When men realize that feminism is a universal good that affects them in very intimate ways then I think they really become allies and leaders.

The Humanist: In May, when President Obama came out in support of same-sex marriage and same-sex parenting, Newsweek’s cover anointed him “The First Gay President.” Maybe it was just a catchy headline but still, it makes you wonder, if he were to come out and say something really bold about women—that we’re truly better off when we can decide how many children to have (or not have)—would we call him “The First Woman President”?

Steinem: No, of course not. We would call him a feminist or a feminist-leaning president. And it also makes little sense to call him a gay president because being gay specifically means that your affectional, sexual energy is, at least some of the time, engaged with people of your own sex.

The Humanist: Journalist and author Susan Jacoby, whose books include the New York Times bestseller, The Age of American Unreason (2008), asks this: Some say the importance of secular women in the feminist movement of the 1970s and ’80s has never been properly acknowledged by leading feminists—as was the case with nineteenth-century feminists. Was there a fear that equality for women would be tarred by ungodliness?

Steinem: I don’t know. I’m more often confronted by women who come from religious traditions and don’t feel that they have a place in the feminist movement. Helen LaKelly Hunt, for instance, wrote a book called Faith and Feminism in which she writes about how the feminist movement seemed so secular to her that she didn’t feel like she belonged. On a personal level, I’ve felt pressure when reporters asked me, “Do you believe in God?” I do say, “No. I believe in people. I believe in nature,” but I still understand how much cultural pressure there is.

The Humanist: There’s a lot at stake. Elizabeth Cady Stanton was a feminist, but she was a freethinker and so her relationship with Susan B. Anthony was strained in that regard.

Steinem: It has so much to do with what feels like home to us. It makes such sense to me to say that many of us are trying to rescue the good in what we grew up with. There’s a lovely poem by Alice Walker in which she talks about being taken as a little girl to a church by the women in her family. She talks about the church service. She’s leaning against the women’s knees and she’s listening. She says, “I think about it now and salvage mostly the leaning.”

The Humanist: In the introduction to your 1983 book, Outrageous Acts and Everyday Rebellions, you talked about the need for a female-controlled magazine for women and some of the challenges you faced with Ms., for instance, convincing advertisers that women would look at an ad for shampoo without an accompanying article on how to wash their hair. “Trying to start a magazine controlled by its female staff in a world accustomed to the authority of men and investment money should be the subject of a musical comedy,” you wrote. What do you miss most about being involved in the day-to-day operations of Ms.? Are you happy with where it’s at today?

Steinem: What I miss most are the editorial meetings. In some sense, to me, life is an editorial meeting. But ours were so free and open and full of spark. They included pretty much the whole staff and people who just wandered by and people who were visiting, so they were quite open meetings and quite different from the ones at New York magazine, where everyone was looking at [editor-in-chief] Clay Felker to get his approval.

Steinem: What I miss most are the editorial meetings. In some sense, to me, life is an editorial meeting. But ours were so free and open and full of spark. They included pretty much the whole staff and people who just wandered by and people who were visiting, so they were quite open meetings and quite different from the ones at New York magazine, where everyone was looking at [editor-in-chief] Clay Felker to get his approval.

I do wish Ms. was still a monthly magazine rather than a quarterly, but it has a life online as well. It also has a lot of currency on campuses, where more classrooms are using it. Ms. also has a prison program so that women who are incarcerated can get free subscriptions.

The Humanist: There’s still a perception that the feminist movement is white women’s territory; that they’re not really reaching women of color. And, unfortunately, in this country it’s mostly women of color who are incarcerated. Do you feel like the magazine is doing a good job of tailoring its content to these groups?

Steinem: I think so. Ms. has published many articles about prison practices that have had an impact. But there shouldn’t be just one magazine either. Of course there are others— there’s Bitch and Bust and other feminist magazines. There should be distinct voices for whatever the experience is.

Regarding the idea that the women’s movement is white and middle class—a fair share of the country is white and middle class. And certainly, there are racist white women. Certainly, there are sexist black men. All those things are true. But the other thing that’s never said is that black women are much more likely to support feminist issues than white women. It makes sense because they’re much more likely to be on the paid labor force than white women. And if you’ve experienced discrimination for one reason, you’re probably more likely to recognize it for another reason.

Personally, I learned feminism disproportionately from black women. Women in the National Welfare Rights Organization, for instance. (They did an amazing, funny analysis of the welfare system as a gigantic husband, jealous and looking under the bed for another guy’s shoes). My long-time speaking partner, Flo Kennedy, is another who taught me, as did Margaret Sloane, who was editor of Ms. and a poet. To say it’s a white, middle-class movement renders invisible all the black women who were there from the beginning, along with groups like the National Black Feminist Organization.

The Humanist: So you’re saying it’s a little bit of a myth.

Steinem: It’s a purposeful myth meant to divide and conquer, especially the middle class part. If you think about Martin Luther King and others in the leadership of the Civil Rights movement, they were all college-educated, middle class people. Nobody tries to diminish the Civil Rights movement by saying they were middle class.

It’s true that the National Organization for Women in its early years was white middle class. But once it was joined by younger women from civil rights groups like SNCC (Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee) it changed profoundly. In any case, my life’s ambition is to make white women as smart as black women. Because the group of women who still vote against their own self-interest are white married women. Single white women don’t; they mostly vote for their own self-interest.

The Humanist: In a Gallup poll conducted in May, 68 percent of Americans with no religious attachment identified as pro-choice; 19 percent identified as pro-life. The nonreligious were categorized as the most supportive of choice among demographic subgroups. My question is: Do you think that opposition to reproductive rights is largely based on religious grounds?

Steinem: I’m not sure because the truth of the matter is that if you look at those who actually have abortions, it turns out to be relatively equal among religious and nonreligious women.

The Humanist: What do you think of the U.S. Catholic sisters who were reprimanded for not speaking out strongly enough against gay marriage, abortion, or the notion of women priests? They were actually faulted for focusing too much on poverty and economic justice.

Steinem: I was perversely delighted to see the Catholic Church and the Vatican go after nuns because I think they made a major error. People are quite clear in viewing nuns as the servants and the teachers and the supporters of the poor. You contrast that with the fact that the Vatican did virtually nothing about long-known pedophiles, and it’s just too much.

Their stance on abortion is also quite dishonest historically, because as the Jesuits (who always seem to be more honest historians of the Catholic Church) point out, the Church approved of and even regulated abortion well into the mid-1800s. The whole question of ensoulment was determined by the date of baptism. But after the Napoleonic Wars there weren’t enough soldiers anymore and the French were quite sophisticated about contraception. So Napoleon III prevailed on Pope Pius IX to declare abortion a mortal sin, in return for which Pope Pius IX got all the teaching positions in the French schools and support for the doctrine of papal infallibility.

The Humanist: It’s interesting how there’s always some very naturalistic reason why these positions are held and why it’s in the power brokers’ best interests to promote them.

Steinem: My favorite line belongs to an old Irish woman taxi driver in Boston. Flo Kennedy and I were in the backseat talking about Flo’s book, Abortion Rap (1971), and the driver turned around and said, “Honey, if men could get pregnant, abortion would be a sacrament.” I wish I’d gotten her name so we could attribute it to her.

The Humanist: On June 5 the Paycheck Fairness Act failed in the U.S. Senate. All Republicans voted against it including female senators, some of whom said it would lead to excessive litigation or hurt small businesses to require employers to demonstrate that any salary differences were not gender-based. Others felt that existing laws like the Lilly Ledbetter Act are protection enough. Do you think there is any merit to those justifications?

Steinem: No, because the Lilly Ledbetter Act was quite specific about addressing the statute of limitations for pursuing an equal-pay lawsuit; it’s a separate question addressing a hole in the law that says that the date it becomes actionable is when the pay is unequal, not when you learn about it.

This war against women started a long time ago with old Democrats who took over the Republican Party, which was, before that, the very first to support the Equal Rights Amendment. Even when the National Women’s Political Caucus started, there was a whole Republican feminist entity. But beginning with the Civil Rights Act of 1964, right-wing Democrats like Jesse Helms began to leave the Democratic Party and gradually take over the GOP.

So I always feel I have to apologize to my friends who are Republicans because they’ve basically lost their party. Ronald Reagan couldn’t get nominated today because he was supportive of immigrant rights. Barry Goldwater was pro-choice. George H.W. Bush supported Planned Parenthood. No previous Republicans except for George W. Bush would be acceptable to the people who now run the GOP. They are not Republicans. They are the American version of the Taliban.

The Humanist: Exactly. And you’ve got a marriage of convenience with the religious right and powerful moneyed interests.

Steinem: Like the Koch brothers. They’ve taken over one of our two great parties. This causes people to wrongly think that the country is equally divided but if we look at the public opinion polls, it isn’t. So, I can’t think of anything more crucial than real Republicans taking back the GOP.

The Humanist: So are you going to go on the road promoting the Republican presidential candidate?

Steinem: No. But I think feminists and progressive Democrats err when they accusingly say to Republican women, “How can you be a Republican?” Nobody responds to that. But if you say, “Look, you didn’t leave your party. The party left you. Let’s just look at the issues and see what they are and forget about party labels and vote for ourselves,” I think people would really respond.

The Humanist: Greta Christina is a feminist and atheist writer and speaker whose blog is very popular in the atheist community. Her question is: Do you think policies and attitudes about sex work should be informed by the voices of sex workers? What do you think of the “Nothing About Us, Without Us” demand that many sex workers are making in regard to sex work laws and policy?

Steinem: Of course, someone who’s experienced something is usually much more expert than the so-called experts. If someone wants to be called a sex worker, I call them a sex worker. But there is a problem with that term, because while it was adopted in goodwill, traffickers have taken it and essentially said, “Okay, if it’s work like any other, somebody has to do it.” In Nevada, there was a time when you couldn’t get unemployment unless you tried sex work first. The same was true in Germany. So the state became a procurer because of the argument that sex is work like any other. This is not a good thing.

I also do not feel proud when I stand in the Sonagachi, the biggest brothel area in all of South Asia. It’s in Kolkata, and everything is written in Bengali except “SEX WORK.” And the term is used in various sinister ways by sex traffickers, who even describe what they do—which is to kidnap or buy people out of villages—as “facilitated migration.”

I’ve only ever met one woman who actually was a prostitute of her own free will. She didn’t have a pimp. She could pick and choose her customers. That’s so rare. So we have to look at the reality and not romanticize it. We have to be clear that you have the right to sell your own body but nobody has the right to sell anybody else’s body. No one has that right.

The Humanist: Annie Laurie Gaylor is a long-time feminist and is the co-founder of the Freedom from Religion Foundation. Her question is: In terms of women’s plight in Islamic societies, did the Arab Spring do anything for women?

Steinem: Yes. The Arab Spring did a great deal for women because the person who spread the word in the first place was a woman. Women participated in it; they were fully out there in the street. Nawal El Saadawi is a founding figure of Egyptian and Middle Eastern feminism who wrote a book opposing female genital mutilation (of which she is a victim). She’s been banned. She’s been in prison. She’s now in her eighties and during the Arab Spring she was like the wise woman of Liberation Square, sitting in the middle of it as young women and young men came to her for instruction, for blessings, and so on.

But it’s very often the case with revolutionary moments that women are present but then they’re drummed out of it afterwards. The worst case in my memory was the Algerian revolution. Because women were so much a part of that and they were told that when the French were gone, everything would be fine. But actually what happened was the re-Islamization of culture to the degree that the suicide rate among women went up dramatically. It was incredible. To some extent we don’t know yet with the Arab Spring.

The Humanist: Can you tell us a little bit about the Women’s Media Center, its purpose and current activities?

Steinem: About five years ago it dawned on me, Robin Morgan, Jane Fonda, and others that while there were more women in the media now, there wasn’t a place for them to gather, and that they had no advocate on the outside. Also, women who were very expert and should be spokespeople in the media were not being made to feel comfortable, or being trained or helped to get booked.

So we decided to start the Women’s Media Center, which is really devoted to making women more visible and powerful in the media in a wide variety of ways. The WMC has a website. It publishes original material. It has a very sought-after training program so that women who are experts have a path into the media. It has particular projects like Women Under Siege, which is drawing the connections and parallels between, say, the new revelations of the sexual abuse of Jewish women during the Holocaust and more recently in Bosnia and the Congo, trying to make what have been isolated stories connect in a way that’s instructive. To see a woman who survived being raped in the Congo listening to a woman talking about something very similar that occurred in a concentration camp, a woman she perceives as an older, wiser, or more powerful woman from another place—this kind of sharing really helps women know they’re not crazy. They’re not alone. I think that’s the state of human rights now.

The Humanist: This almost seems trivial compared to what you were just talking about, but the Women’s Media Center supported Sandra Fluke when she testified before Congress. Of course, she was attacked by Rush Limbaugh, but more recently the WMC came out in support of another woman, S.E. Cupp, a conservative commentator who supports the defunding of Planned Parenthood. Can you talk a little bit about what happened to her?

Steinem: The point is that women should be covered fairly. For example, I didn’t want to read that Sarah Palin couldn’t be in political office because she had young, dependent children or hear only about what she was wearing, not about her views and so on. So we did defend Palin and we defended Cupp, too, because she was pictured in Hustler with a penis photoshopped in her mouth. It was so ridiculous. It’s very important to defend basic principles whether they’re happening to your friend or your not-such-a-friend.

The Humanist: Returning to Sandra Fluke, Limbaugh famously dubbed her a slut. Feminists have been actively reclaiming that term with SlutWalk marches and now there’s a “Rock the Slut Vote” campaign to focus on women’s issues in the upcoming election. Didn’t you employ some similar tactics in the 1970s? Why is it an effective strategy to reclaim certain words?

Steinem: I think most social justice movements take the words that are used against them and make them good words. That’s partly how “black” came back into usage. Before we said “colored person,” or “Negro.” Then came “Black Power,” “Black Pride,” and “Black Is Beautiful” to make it a good word.

“Witch” was another word I remember reclaiming in the 1970s. There was a group called Women’s International Terrorist Conspiracy from Hell (WITCH). They all went down to Wall Street and hexed it. And Wall Street fell five points the next day; it was quite amazing! “Queer” and “gay” are other examples.

The Humanist: And isn’t it true that these words can only be reclaimed by the members of that group?

Steinem: That’s right. I think we all have the power to name ourselves. I try to call people what it is they wish to be called. But we can take the sting out of epithets and bad words by using them. Actually, I had done that earlier with “slut” because when I went back to Toledo, Ohio, which is where I was in high school and junior high school, I was on a radio show with a bunch of women. A man called up and called me “a slut from East Toledo,” which is doubly insulting because East Toledo is the wrong side of town. I thought, when I’d lived here I would have been devastated by this. But by this time I thought, you know, that’s a pretty good thing to be. I’m putting it on my tombstone: “Here lies the slut from East Toledo.”

The Humanist: That is really funny. You know, something that struck me at the Women in Secularism conference is that the older women on the panels were strong and they were forceful, but they didn’t employ humor the way the younger women did. And the other thing I noticed was that the younger women’s humor sometimes had a self-deprecating tone. For feminists, do you think there’s a line we shouldn’t cross in this sense?

Steinem: There were never that many women stand-up comics in the past because the power to make people laugh is also a power that gets people upset. But the ones who were performing were making jokes on themselves usually and now that’s changed. So there are no rules exactly but I think if you see a whole group of people only being self-deprecating, it’s a problem.

But I have always employed humor, and I think it’s absolutely crucial that we do because, among other things, humor is the only free emotion. I mean, you can compel fear, as we know. You can compel love, actually, if somebody is isolated and dependent—it’s like the Stockholm syndrome. But you can’t compel laughter. It happens when two things come together and make a third unexpectedly. It happens when you learn something, too. I think it was Einstein who said he had to be careful when he shaved because if he thought of something suddenly, he’d laugh and cut himself.

So I think laughter is crucial. Some of the original cultures, like the Dalit and the Native American, don’t separate laughter and seriousness. There’s none of this kind of false Episcopalian solemnity.

The Humanist: Going back to our discussion of self-identifiers, there’s a lot of talk within the secular movement about reclaiming the word “atheist.”

Steinem: If it were up to me, I would not define myself by the absence of something; “theist” is a believer, so with “atheist” you’re defining yourself by the absence of something. I think human beings work on yes, not on no.

The Humanist: So “humanist” is sort of a beautiful term then.

Steinem: Yes, humanist is a great term.

Jennifer Bardi: Do you consider yourself a humanist?

Steinem: Yes, a humanist except that humanism sometimes is not seen as inclusive of spirituality. To me, spirituality is the opposite of religion. It’s the belief that all living things share some value. So I would include the word spiritual just because it feels more inclusive to me. Native Americans do this when they offer thanks to Mother Earth and praise the interconnectedness of “the two-legged and the four, the feathered and the clawed,” and so on. It’s lovely.

The Humanist: So we need a more positive and inclusive term.

Steinem: Yes, because it’s not about not believing. It’s about rejecting a god who looks like the ruling class.

The Humanist: Some people call themselves post-theological, which is kind of a mouthful.

Steinem: It’s kind of great though. I like to say that the last five-to-ten thousand years has been an experiment that failed and it’s now time to declare the first meeting of the post-patriarchal, post-racist, post-nationalist age. So let’s add “post-theological.” Why not?