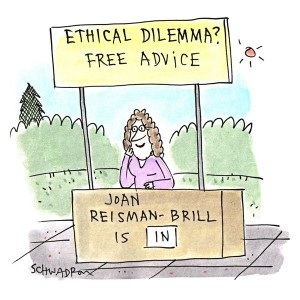

The Ethical Dilemma: My Father is Sick, and Everyone Wants to Pray for Him. How Should I Respond?

Experiencing an ethical dilemma? Need advice from a humanist perspective?

Send your questions to The Ethical Dilemma at dilemma@thehumanist.com (subject line: Ethical Dilemma).

All inquiries are kept confidential.

Don’t Pray Can’t You See: My father has been very ill for a long time, and while I appreciate the care and concern that a lot of people express to me about his well-being, I’m getting really tired of all the messages where people tell me that “we’re continuing to pray for him.” I don’t believe in prayer and it seems disingenuous every time I say “thank you” to people who say they’re praying for him. What I really feel like saying is, “Could you do something more useful?” I’ve opted not to say anything because I know they’re well-intentioned, but on the other hand I feel like I’m having to suppress my identity. Is there a graceful way out of this?

—Thanks, But No Thanks

Dear Thanks,

I recently experienced the same problem first-hand (or first- and second-foot) and wrote an article about it. When a friend’s mother died, he was really irritated every time people told him they were sorry. He just hated that phrase. Why were they sorry? It wasn’t their fault, and they weren’t experiencing the loss he was. As I tried (without success) to explain, people often flounder around when they attempt to express their sympathy and good wishes, so they fall back on tired, meaningless or misguided platitudes. So if you can look past the inadequate words to the humane impulse behind them, your simple thank-you is an appropriate response.

In the case of the people who say they are praying for your father, some actually are praying and believe that their entreaties to a supernatural power really have some effect. If these are the same people who say, “Let me know if there’s anything I can do for you” (another thing people say and may or may not mean), be ready with a few things to suggest. For example, ask them to visit your father, take over for a few hours or a day so his caregivers (you?) can get time off, bring his favorite foods or cook and serve him a meal, take him out if he’s up to it, etc.

You can certainly inform people that you don’t believe in prayer and would appreciate something more useful, but you know you will disturb them by pointing that out. Still, those who genuinely want to help will stick around to do so, and what will you lose by losing the ones who just want to offer lip service? I suppose you should consider how your father feels about these prayers and these people and not do anything that would distress him (such as alienating his friends), but otherwise feel free to go for it. At the very least, it may work better than the “do not call” registry, and perhaps it will get people to recognize what is and isn’t constructive when people are in crisis—regardless of whether they are believers. Even if I were a nun with a broken leg, I’d recover better if people sent me to an orthopedist than if they sent me all the prayers in the cosmos. So speak up—but don’t be surprised if these pious people just add your soul to the to-pray list and plead even harder for your dad.

And here’s an apropos Facebook post (to an earlier column) from Linda Shiflet Pillow: “Once I realized how arrogant and patronizing it was for friends to say they would pray for me, or to suggest that I should be praying, I have learned to ask how they would feel if I told them I would be getting together with my humanist friends and discussing them and hoping fervently that they would renounce fantasy, embrace logic, and find common sense. So far, that has kept them at bay.” Brilliant, Linda!

Confusing The Child: I have a 3-year old son with a man whose “beliefs” are, like mine, nonexistent (agnostic/atheist). His mother prefers that our son have a strong faith in god, of the Christian sort. My son’s father as a child went to church and his stance is to go with the flow and abide by his mom’s wishes. In the past I have received Bible story children’s books from her and have very respectfully told her that I would never read these books to her grandson. She has given Easter chocolate in the shape of a white cross. I put it up in the attic, mainly because he was a baby at the time and couldn’t eat the chocolate anyway.

But what do I do now? I have pulled myself away from both my son’s father and his family, for other personal reasons. So I have very little contact with his family now. However, my son goes to them for Thanksgiving, Christmas, Easter, and non-religious days as well. I would not want to tell people how to treat their own grandchild in their own home. I am concerned though, because he comes back from these visits with stories of Santa Claus and the Easter Bunny—which are all fine and good at 3 years old, even if I would’ve chosen to never introduce these characters to him. But what do I do when he’s older, since they clearly see a belief in god as not only a very important part of their culture, but as the way to raise a good person? This is not what I want for my child. He may choose it later in life, but not now, and not under pressure by me or anyone else.

I worry that it may be the tip of the iceberg as far as religion goes, so I don’t know how to constructively approach his father or his grandparents or just try to counter all of these “cultural” stories they are feeding him with stories of my own—which means I would have to create some because I don’t have any.

When my toddler goes on and on about Santa Claus/Easter Bunny coming to his grandparents’ house, am I being a grouch by saying that character isn’t real, just like Mickey Mouse? Am I not letting him “just be a kid” by telling him the things that his grandparents are telling him are real actually aren’t? I grew up without a belief in any of these things and I have only very fond memories of a wonderful childhood. And actually knowing the toys/sweets I received were through my parents’ hard-earned money did in no way ruin my appreciation of the gifts; indeed, it added to my appreciation of my wonderful parents.

—Feeding My Kid Faith-Laced Treats

Dear Faith-Laced,

I hope that white chocolate cross is no longer in your attic! Next time, immediately either give it away, or chop it into bite-size chunks and enjoy it. Nothing is gained by hanging on to unwanted symbols, however sweet.

And nothing is gained by hanging on while the father’s family takes your son for a ride. First question is what is your legal situation? Does the father support your son, have joint custody, visiting privileges, etc.? Please check with a lawyer about your rights and his. It’s wonderful that you are so accommodating, but the father’s family is imposing their values on him, and he’s allowing them to impose them on your son. The grandparents are not in charge, and yet they blithely ignore your very clear instructions that you don’t want crosses, chocolate or otherwise, for your son, while his father facilitates their imposition. Understanding your legal rights becomes even more important in the event that you and/or the father become involved with other partners, who may introduce new issues or exacerbate the current ones.

Perhaps you could change the visiting days so they don’t fall on Christian holidays. You could insist that the grandparents desist and, depending on your legal status, you may be able to enforce it. But if you want (or must) keep the father and his family in your son’s life, you need to do so as amicably as possible, which means you may have to continue to allow them to express their love for him (and disrespect for your beliefs) the way they do. Bear in mind that it’s really not going to do long-term harm to your son, any more than learning that Santa isn’t real crushes children raised in religious homes. Your son will come to understand that dad’s family has one set of beliefs and mom has another.

And don’t confuse your lack of a religion with an absence of a culture. You certainly do have stories of your own to impart to him, and perhaps relatives and friends to reinforce your perspective. Continue to tell your son the truth (which makes you honest and trustworthy, not a grouch), share tales of your cherished agnostic upbringing, introduce him to secular organizations and books and movies and arts. Maybe you and he can participate in local humanist groups and children’s programs.

And remember, “The hand that rocks the cradle rules the world.” As the parent he lives with, you have the greatest influence over his education and development. You already sound like you’re doing a wonderful job. Just keep doing it, and he’ll have happy memories of childhood as you do—just different.