Carnival or Campaign? Locating Robin Hood and the Carnivalesque in the U.S. Presidential Race

N. C. Wyeth (1882-1945): Robin Hood Defeats Nat of Nottingham at Quarter-staff

N. C. Wyeth (1882-1945): Robin Hood Defeats Nat of Nottingham at Quarter-staff “Fundamental reform to expand and deepen our democracy, we know from America’s history, follows from one thing only: mass movements.”

—Robert Weissman, Public Citizen News, January/February 2016

SERIOUS VIEWING of the televised campaign to select the 45th president of the United States has been difficult for many of us. Most of the seventeen original GOP candidates were quickly outdone by unusual debating tactics, including Donald J. Trump’s “presentation of self.” As Irving Goffman pointed out in 1959, we all have multiple “selves” which we choose to present differentially to people and audiences. Some contemporary political pundits say Trump’s performance reminds them of a circus or carnival. True enough, but better understood if one knows the work of Mikhail Bakhtin, a Russian scholar who, writing in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, discussed the evolution of the early Christian pre-Lent festivals of the Middle Ages in terms of their impact on the social order. He believed that carnival was not only not an impediment to revolutionary change, but that it was revolution itself.

Indeed, Bakhtin attributed much of the democratization of the Renaissance in fourteenth- through sixteenth-century Europe as having been stimulated by activities of the lower classes, acting not as individuals but as a crowd. He suggested that at carnival time, the unique sense of time and space caused individuals to feel they were part of the collectivity, at which point they ceased to be themselves. Does this ring any bells?

Also of interest, and pertinent to the argument here, are the thousands of European legends of Robin Hood, which illustrate how carnival-like behavior, termed “carnivalesque” by translators of Bakhtin, accompanied the behavior of many of these so-called bandits turned heroes (or sometimes vice versa). In early modern England, for example, the original population had been seriously downgraded for more than two hundred years by invasions of different kinds of foreigners—Romans, Germanic tribes, Saxons, Vikings, and especially the French-speaking Normans (even though he was sometimes said to have been a member of the Saxon aristocracy himself). As the legends go, Robin Hood was indeed an agent of social change. History or folklore, it is a story whose “truth” has been a model and an inspiration for several hundred years in many countries.

The values of early modern European and English peasants focused upon success in maintaining their home, hanging onto and increasing their land holdings, and getting a good harvest—which compares to the values many Americans hold as they contemplate their vote in 2016. So let us draw this comparison even further with what we’re witnessing today.

Trump’s early campaign performances garnered an almost immediate fan base that rapidly increased and spans various components of the U.S. population. His fans and followers are ready to vote him into the White House, thus dismaying many of the GOP elite. His admirers seem united primarily in their desire for massive change in a government that no longer seems capable of doing what modern democratic governments are expected to do—namely, keep the peace, protect the citizens, preserve the natural environmental health and wealth, and create legal and economic measures to enable citizens to live a good life. It may also be that they believe the country is headed to hell via terrorist immigrants, legal marijuana, gays everywhere, and a life without personal gun ownership. In either case, they see in Trump a forceful person who can make things better all by himself.

What things? Well—better education to help them find more jobs, with higher pay, better working conditions, control of crime, protection from local and global terrorism, and a cessation of immigration by those they believe are undesirable and either dangerous or likely to compete with them for the “good life” which they once enjoyed or are still seeking. Trump’s supporters are smitten by his performance and wooed by his promises to almost instantly improve the status of both the country as a whole and themselves. Ironically, they seem unable to recognize that he too is a member of the very well heeled, dominant U.S. “establishment.” The fact that he’s never occupied any elected office in our government is seen as a plus.

Enter two, in some ways similar candidates on the Democratic side. Senator Bernie Sanders (D-VT) and Hillary Clinton, former U.S. senator and former secretary of state, have long held positions (elected, appointed, and voluntary) in our national government, yet must face the same angry voters seeking massive change led by a “new guard” in Washington, DC. As has become very clear, however, both have adopted and discussed ideas as to the changes they would make if elected. Sanders has gone so far as to call his views “democratic socialism.” He dissociates himself from Wall Street, major banks, and large corporations, along with many of the laws, tax codes, trade agreements, and other decisions that, in his opinion, make the goal of a good life less possible for the newest cadre of young Americans. He has succeeded in aligning himself with the poor “others” of our population, in opposition to the 1 percent who are said to control 90 percent of personal wealth in the United States.

Hillary Clinton shares many of his views, has adopted the term “equality gap” as something she wants to reduce, and has repeatedly spoken of some of the measures she would take to help this along, pointing to her previous efforts in helping to improve health and educational matters. As such, she could also be considered something of a Robin Hood (especially since sexual “inversions” were common in early carnival behavior). Both she and Sanders recognize that sociocultural diversity within our country is increasing, and that rampant global and national population growth, environmental destruction, economic competition from other developing nations, the aging of our own infrastructure, and other factors must be recognized, harnessed, and corrected in order to regain and retain the promise of our founders.

It is certain that without meaningful change, the anger of the populace is bound to increase, just as it has in history elsewhere. To respond to such anger, the American public must try to understand the nature of different sociocultural systems through time, and how we came to have a country that has been the envy and model for the world since Athens invented democracy.

The United States of America, despite the dream of equality promised in our Constitution, has never really been a “melting pot.” From earliest colonial times we have been more like a tossed salad in terms of race and culture. Yet the ingredients of that salad have not had equal status or benefits within the whole. Throughout our history we have also suffered petty and serious crimes of various sorts, including slayings of innocent people in the streets, schools, churches, and theaters, as well as in our homes, sometimes by family members. Justice, however, has not been equal for all victims or for the accused perpetrators—it has instead favored the wealthy and the more powerful, thus filling our jails with people of color and of non-European extraction. It took a bloody war to eliminate legal slavery and preserve the nation, but it left behind a lasting inequality for those with darker skin.

The United States of America, despite the dream of equality promised in our Constitution, has never really been a “melting pot.” From earliest colonial times we have been more like a tossed salad in terms of race and culture. Yet the ingredients of that salad have not had equal status or benefits within the whole. Throughout our history we have also suffered petty and serious crimes of various sorts, including slayings of innocent people in the streets, schools, churches, and theaters, as well as in our homes, sometimes by family members. Justice, however, has not been equal for all victims or for the accused perpetrators—it has instead favored the wealthy and the more powerful, thus filling our jails with people of color and of non-European extraction. It took a bloody war to eliminate legal slavery and preserve the nation, but it left behind a lasting inequality for those with darker skin.

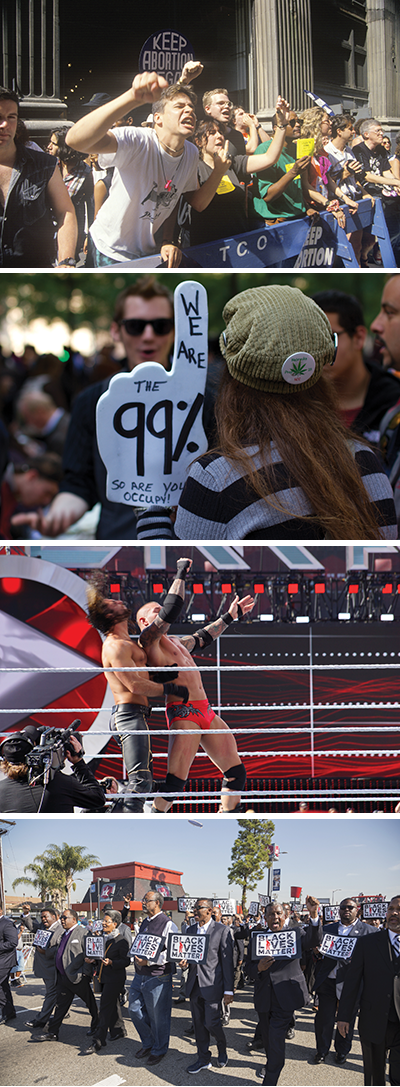

Such calamities are now matched by mass protests against “the police,” “Wall Street,” banks, and various other corporate entities. “Black Lives Matter” is countered by “All Lives Matter,” and violence extends not only to property destruction, but to attacks on individuals of the “other” category, however defined. The polarization of political parties has contributed to the development of an ineffective Congress and the president’s loss of status and power. Thus, the country hasn’t been able to accomplish much to alleviate, much less eradicate, the continuing racial and ethnic tensions, uncertain and underpaid employment, and increasing fear and anger of both the middle class and poorer citizens and visitors who would like to live here now. It is the purpose of this article to suggest a sociocultural perspective, with examples from history.

Let us start with the frequently mentioned notion that for tens of thousands of years, most societies have had their “haves” and their “have-nots.” During the Paleolithic Period, the primary divisions were based on age and sex, complemented and led by those individuals who demonstrated special skills in performing necessary work such as hunting, gathering, and preparation of foods and raw materials for clothing, shelter, baskets, bows and arrows, adornments, and so on.

Women were valued for their participation in all of these, as well as for bearing and caring for children. There are literally thousands of Paleolithic “Venus figures” in museums and private collections throughout the world, many of whom are clearly pregnant, and others simply well-fed and well-endowed. They were admired as women, and, for their economic contribution, as a class. In fact, the plants and small proteins they gathered actually formed the largest part of the diet, since hunting was both more risky and often futile. Artists, dancers, musicians, and those with special knowledge of “bush” medicines were also especially valued. Kinship with any otherwise “successful” person might also have conferred special privileges, and elders without progeny might have been ignored and even left to die. But within the home community, there were no classes with special status or power.

Thus, the equity gap seems to have begun after humans learned to domesticate plants and animals, and became increasingly complicated as time marched on, leading, in the early civilizations, to widespread warfare, slavery, and uneven poverty. Professional ethnography did not really begin until the late nineteenth century, but historical and archaeological studies have taught us that democracy came late. There may have been some rituals that we might characterize as carnivalesque in the Paleolithic Period, but more likely these didn’t occur until the later Neolithic. These included ritual or ceremonial behavior involving masks, special costumes, paintings and figurines of wild animals, as well as songs and chants, body paint, tattoos, and other bodily modifications. However, without a major equality gap, these may be better characterized today as early beliefs in the supernatural, which probably led to different kinds of religious formulations, only some of which might be recognized today.

The Difference between CARNIVAL and CARNIVALESQUE

The concepts and behaviors that characterize the phenomena usually described today as “carnival,” are more reminiscent of the circus, which will not be discussed here, although it’s clear that there is some crossover between the two. These still exist in many countries, with professional companies traveling from town to town where visitors may watch or participate in various activities such as puppet skits, clown shenanigans, “joy” rides, acrobatic feats, and tests of strength or marksmanship with guns or arrows. Carnivalgoers laugh at or are confused by comic sexual inversions, holding their breath while watching the performances of trained animals and other extraordinary acts that mock, ridicule, and, in general, permit and even celebrate behavior and rhetoric otherwise unused and unseen in “nice” (i.e. middle class) society.

Carnival itself was once celebrated by the entire population of a town, thereby uniting the classes, at least momentarily. The word itself is usually explained in terms of prohibitions on eating meat during Lent, along with other privations. The holiday festivities and the “relaxed” notions of what was “good behavior” were thought of as a means of offering some respite for the privations to come, thereby perhaps avoiding open social disturbances or even rebellions. Interestingly, the upper classes eventually ceased to participate, and the celebrations became even more comical and rowdy, and were eventually discouraged by the religion that originated them.

The carnivalesque, then, refers to activities that imitate, or have derived from the original carnivals—some from before and some from the period after the upper classes gave them up. However, most social scientists today would no doubt suggest that some of each kind of behavior persists today in many parts of the world, including the United States, although as purely popular, fun-loving ways of relaxing before having to return to more difficult or onerous tasks and conditions. A recent Internet search of the term “carnivalesque” resulted in the following suggestions for the contemporary United States: reality TV, spring break, Girls Gone Wild, homecoming, costume parties, Saturday Night Live, Halloween, Super Bowl, and Mardi Gras.

The carnivalesque, then, refers to activities that imitate, or have derived from the original carnivals—some from before and some from the period after the upper classes gave them up. However, most social scientists today would no doubt suggest that some of each kind of behavior persists today in many parts of the world, including the United States, although as purely popular, fun-loving ways of relaxing before having to return to more difficult or onerous tasks and conditions. A recent Internet search of the term “carnivalesque” resulted in the following suggestions for the contemporary United States: reality TV, spring break, Girls Gone Wild, homecoming, costume parties, Saturday Night Live, Halloween, Super Bowl, and Mardi Gras.

Religion itself usually plays little, if any part in most contemporaneous carnival or carnivalesque behavior, although that is arguable for the present campaign, which has included, ironically, jokes about some of the beliefs of citizens and/or candidates, as well as desultory remarks about some “non-establishment” belief systems. Rather, the term “carnivalesque” is more appropriate and better illustrated by remarks used in describing various activities, such as private political “get-togethers,” mass protests, displays of violence, and occasional “pranks” by both the candidates and their followers.

For our purposes, then, both carnival and carnivalesque can be thought of as products of plural societies with a serious equity gap, where forces on each end worry about how to control, if not eliminate, the other. Which of the presidential candidates, then, best embodies or utilizes the carnivalesque spirit?

Photo © Charlie Leight

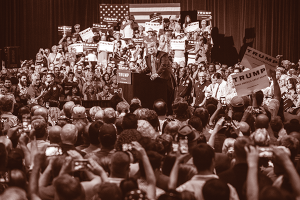

Donald Trump is one of the few contemporary presidential hopefuls who has never held any governmental position. He is nevertheless well known to most Americans. His lavish lifestyle, supported by his colorful international business activities and romances, together with a “reality” television show in which he starred and dominated, clearly identify him as a member of the economically elite “establishment,” even as he proudly positions himself as outside of conventional political circles.

As Trump continues to amass delegates on the strange road to the GOP nominating convention, his audiences remain huge, and one continues to wonder who Trump’s supporters are and why they continue to come to him. Is it mainly for the entertainment, or do they perhaps have questions about serious issues? Perhaps, they’re only looking to assuage their anger.

There are estimates of the race, national origin, age, gender, educational level, employment status, and religion among Trump’s supporters. It is said that his followers are largely white men of all ages and religions, in or out of blue-collar employment, with relatively little higher education. One view is that the majority are inherently “authoritarians” by nature who admire Trump’s promises to simply “take over” and “fix” anything he wishes once he becomes president. Their anger can be temporarily put aside as they fantasize about the new future they believe he can arrange. Some would like to “go back” to a previous world that has inexplicably “gone wrong” while others dream of something entirely new—a revolution, perhaps? They brandish Trump posters, wear Trump t-shirts, and, more recently, clap, cheer, cuss, and act out violently against those who dare criticize their hero, especially if he seems to be encouraging their behavior. “So if you see someone about to throw a tomato, knock the crap out of them, would you?” Trump jovially implored the crowd at a rally in February, referring to anyone who might try to disrupt what he claims are “lovefests.” All this fits in with and enhances the carnivalesque nature of the rallies. And if by chance his supporters are detained by the police, Trump even promised several times to pay the fines. (Robin Hood also helped his followers evade the sheriff.)

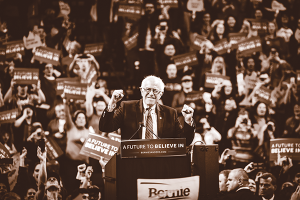

Photo © Nate Gowdy

Enter Bernie Sanders, who calls himself a democratic socialist, which some, unfortunately, link with communism. And indeed, he even speaks approvingly of revolution, praising Cuba and other nations that have taken that route in the past. The fact that most of those nations have come to realize that revolution fails to resolve many problems and creates others is another unappreciated historical fact.

Yet Sanders, like Trump, attracts thousands of followers who are entranced by the promises he makes, even if he cannot explain just how he can bring them to pass. No matter—like the rhetoric, violence, feasting, and celebratory aspects prominent in the tales of Robin Hood, there is a carnivalesque attraction here, so let us try to understand it, both for the present and in historical terms.

Whether anti-establishment voters will continue to follow the candidate who provokes, humiliates, and angers his competitors, or one who makes promises to bring about a utopia without explaining its possible risks to the country, both personalities clearly please, thrill, and motivate much of the public, who “eat up” the rhetoric and contribute to the “holiday” nature of their experience.

And the adulation of the crowds, along with their questions, their hopes, and their fears, are the fuel that will hopefully remain with both “Robin Sanders” and “Robin Trump.” Like many of the carnivalesque leaders in earlier societies, their candidacies really might help produce some of the changes in policy needed to respond to those searching for the so-called cup of liberty before the revolutionary impetus goes too far among the disadvantaged.

In pondering the behavior of the electorate, some analysts have suggested that large swathes of the U.S. populace are demoralized by what they perceive as rampant destruction of social property (of religious meeting places, office buildings, stores, and so on)—by organized groups as well as individual “lone wolves.” Popular anger everywhere has led to further social distress, including suspicion and prejudicial feelings and behavior between those of the establishment and the less well-off segments of the populace, some of whom have actually chosen to desert their homes to join more radical groups abroad.

It’s true that despite the differences and prejudices still persisting among different groups, many individuals have indeed chosen (usually because of their inherited or acquired special talents, luck, or hard work) and have been accepted into the upper “class,” a status formerly accorded primarily to so-called WASPS. Recognizing this should be a warning against “profiling”—i.e., judging an individual’s social status by his or her appearance alone.

Let us also recognize that “others” in the U.S. equity-gap now include many of the aging; teenagers; gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgendered individuals; “wounded warriors” and other persons with physical disabilities (either genetic or due to accidental incidents); and members of various religious beliefs, especially if their dress or language reveal that connection. Their status is certainly related to the decline of the extended family, as well as to a more openly expressed societal prejudice against persons with their characteristics. We should keep in mind that many of these people are also feeling angry or bitter about their lives, and they also vote.

Bakhtin suggested that poplar uprisings seem always to have arisen when the equality gap grew too great. And although the local establishment always survived the popular inversions in language, the nasty tricks, and the general behavior of the masses and their leaders, some relief for those at the bottom was often a result.

The Violence of Representation (1989, edited by Nancy Armstrong and Leonard Tennenhouse) contains an essay by Peter Stallybrass titled, “‘Drunk with the Cup of Liberty’: Robin Hood, the carnivalesque, and the rhetoric of violence in early modern England.” In it he quotes Josiah Tucker, Dean of Gloucester, who in 1745 said of the “lower class of people”:

Such brutality and insolence, such debauchery and extravagance, such idleness, irreligion, cursing and swearing, and contempt of all rule and authority . . . . Our people are drunk with the cup of liberty.

If we are to glean anything positive from the 2016 presidential campaign, let it be in the comparison of candidates Trump and Sanders to Robin Hood set loose in the intoxicating carnivalesque of the campaign, where eventually they will help us maintain what we like about our country, but also stimulate those with power to soberly bring about some—or even considerable—relief of from our current social woes.