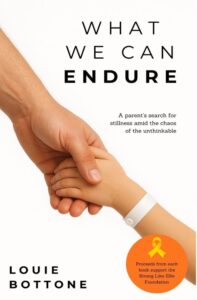

Book Excerpt: “What We Can Endure”

The day that Ellie was diagnosed with leukemia, the world did not change in the dramatic ways people describe. The sky did not darken. The ground did not give way. The Earth did not stop spinning. Quite the opposite. The grocery store clerk bagged groceries while making small talk about the weather. Obliviously, strangers asked how my day was going. The hotel guests in the room next store still partied throughout the night. The universe, it turned out, was under no obligation to notice our grief.

Nor did the universe care that I was a thousand miles away from Ellie when the diagnosis came. There was no mercy for the fact that we were in the middle of a cross-country move. The tests results arrived just hours before we were supposed to be closing on our dream home. Overnight, mortgage paperwork was replaced by leukemia treatment pamphlets.

The disbelief came first. I was paralyzed. It was like being punched in the gut by something you didn’t know could even hit you. Cancer? No. That wasn’t on the table. Ellis isn’t even three years old. Toddlers don’t get cancer. That’s not how life works.

“Why?” is the most natural question in moments like these. It rises instinctively, almost reflexively, as though it has always been waiting just beneath the surface. Why her? Why now? Why would something like this happen to a child who has barely had time to become a person? Why would a universe that contains so much joy, beauty, and love also allow this horrible suffering?

“Why” carries with it an unspoken assumption: that somewhere there is an answer capable of making sense of what has happened. That suffering, especially innocent suffering, must be justified by something larger than itself. That pain must eventually resolve into meaning, if only we search hard enough for the explanation.

And so, I searched. I searched not because I believed the universe owed me an explanation, but because I could not yet imagine enduring a reality that didn’t have one.

I searched in philosophy, in the language of fate and randomness, in the idea that bad things simply happen and that this, somehow, was supposed to be comforting. I listened as people offered explanations meant to soften the blow. Some were well intentioned. Others were careless and cruel without meaning to be.

I didn’t think of the question of meaning as religious, but I recognized the shape of it. Embedded within “why” was the assumption that suffering must be justified. That pain must have a higher purposes; the end must justify the means.

I heard it in conversations with friends, family, and strangers. “Everything happens for a reason,” I was told. “Trust in God’s plan. Ellis is strong. Mercy to the Lord that it was caught early. You’ll understand soon. You’ll be grateful this one day.”

To be clear, the people who said these things meant well. Just like the glances that Ellie’s bald head got at the playground, there was no intentional cruelty. In fact, I believe many truly did find comfort in what they were saying. They believed in a God who allowed this for a reason beyond understanding. They accepted that the explanation was out of reach, but real nonetheless.

When someone said, “God has a plan for her,” or “this is happening to her for a reason,” it wasn’t just a throwaway platitude. It was a sincere attempt to offer hope. It was an invitation to believe that Ellie’s suffering was not meaningless. A reminder that one day, the reason would reveal itself as part of a greater good.

I understand why people cling to that. It’s a lifeline when hope runs thin. It turns chaos into choreography, pain into purpose. It’s a tempting reassurance, especially when the alternative is accepting that sometimes there is no reason. I’ve reached for that same certainty before, when I couldn’t stand to look into the abyss of randomness.

But that framing, however well-intentioned, carries an invisible cost.

It implies that Ellie’s pain was necessary. That the hospital beds, the needles, the nausea, and the fear were all meant to happen. It suggests that the suffering of an innocent child was a deliberate part of a cosmic plan, an essential variable in some divine equation whose solution we’re not allowed to see.

But even if someone truly believes that, it’s useless to a parent standing beside their child’s hospital bed. In fact, it’s more than useless. It’s crushing. It rebrands cruelty as design. It turns tragedy into divine intent. And it implies we should be okay with it, because God must have a reason.

But the offerers of this ‘wisdom’ were not there. They weren’t in my hotel room, a thousand miles away from my daughter when my worst nightmare came true. They didn’t have to pull her red curls from the hairbrush when the chemotherapy side effects began. They didn’t mop up vomit at 2 a.m. for the third night in a row. They didn’t hear Ellie’s screams of “Please Daddy, help me” when the nurse approached with the catheter. They don’t relive those moments. They don’t wake from nightmares where Ellie relapses. If they did, I wonder if they‘d still call it God’s plan.

I did not want Ellie’s suffering to mean something. I wanted it to stop. Slowly, I began to see that the “why” question I was asking was not unanswered; it was unanswerable.

As humans, we are wired to find signal in the noise, to chase purpose through pain. But in this case, there was no greater plan, no moral test, no karmic debt. Just a random, catastrophic biological error that entered Ellie’s bloodstream.

As Christopher Hitchens once wrote, “To the dumb question ‘Why me?’ The cosmos barely bothers to return the reply: ‘Why not?’”

“Why did this happen?” assumes a universe that distributes suffering according to reason or fairness. It assumes intention. It assumes explanation. It’s staring at the mountain and inventing reasons for its existence rather than asking how it came to be. Soon, I learned that “how” is the only question that leads us anywhere useful.

“Why” distracts us from solutions. “How” shifts the problem into the realm of science, not metaphysics. We can study, test, and understand. We can uncover mechanisms, identify causes, and work toward prevention or eradication. We can treat leukemia not as a divine message, but as a biological flaw to be solved. That is helpful. That is progress. Shrugging our shoulders at a “mystery” is not. We don’t need to preserve the illusion that a hidden purpose makes suffering acceptable. We don’t need to bow to some invisible parent in the sky. We need to roll up our sleeves and make sure no child has to endure it again.

The universe does not explain itself, nor are we owed an explanation. It produces life and loss through the same indifferent processes. Expecting justification is a human impulse, not a cosmic one.

We cannot accept iron-aged superstitions about metaphysical purpose when children suffer in cancer clinics. We must demand better of ourselves and of our leaders. We must stop gazing up at the sky and asking ‘why’ and instead look down into microscopes and ask ‘how.’

How can we ensure no child ever faces what Ellie endured? How can we fund science and health initiatives that eradicate cancer once and for all? How can we continuously march toward reducing suffering in the world? And the ultimate ‘how’ question that drives all of human behavior: how can we make our lives better tomorrow than it was today?

Seeking answers to those questions doesn’t require a divine plan. It requires showing up, choosing action over complacency, and not settling for comforting answers when deeper truths are to be found.

But even answers to the rigid questions don’t tell you how to survive the days that follow. They don’t teach you how to wake up each morning and keep moving when your reserves are gone. They don’t explain how to sit beside a hospital bed night after night without breaking, or how to carry terror quietly enough that your child doesn’t feel it too.

Once I stopped asking the universe to justify itself, I was left with a more intimate problem: what kind of mind does it take to live through this without collapsing under its weight? What kind of framework allows a person to keep showing up when hope feels conditional and the future feels permanently unstable?

Endurance, I began to understand, is not passive. It is not the quiet acceptance of suffering or the belief that things will somehow work out. It’s an active posture. It’s a way of thinking, of choosing, or orienting oneself toward reality as it actually is, not as we wish it to be. It’s the decision to remain engaged, to live only for the next moment, and the one after that, and so on.

“What We Can Endure” tells the story of Ellie’s battle with cancer, but as its core, it is about constructing a mental framework sturdy enough to withstand unbearable uncertainty. When there are no guarantees – no promises that things will work out, no hidden meaning to lean on – what matters most is how we meet what is in front of us. Humanism rejects the idea that suffering must serve a purpose or submit to mystery; it demands that we take responsibility for one another in a universe that offers no such assurances. This book is an attempt to understand what that responsibility looks like in practice, and how we learn to endure when endurance is the only option left.