Film Review: 22 July

Seven years ago—on July 22, 2011—Anders Behring Brevik ignited a car bomb in front of a government building in Oslo, Norway. He then traveled to the island of Utøya, where Norway’s Labor Party was hosting a children’s summer camp. Disguised as a police officer, he lured the camp’s children and staff to him before opening fire. Utøya is a small island—barely twenty-six acres. Brevik stalked the children through the woods and along the island’s bluffs, shooting bodies in the head along the way just to make sure they were dead. By the end, before he was arrested by police, over 300 people were injured and seventy-seven were killed (eight from the government building, sixty-nine from the summer camp).

Brevik had left behind a manifesto—1,500 pages of fascist platitudes about feminists, immigrants, Marxists, “multiculturalists,” and “suicidal humanists.” The conflict between good and evil (what Brevik called “World War IV”) was inevitable, it argued, so “patriots” should strike first by waging “pre-emptive war” against Europe and the West’s “traitors.” Brevik saw himself on the good side. As he was shooting little girls and boys in the head, he thought he was saving Europe, masculinity, and the white race. Hard-heartedness of course always being the first refuge of the weak-minded.

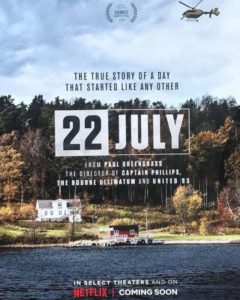

Cinematically portraying this kind of political violence is always difficult. Those trying to do so are caught in a double-bind. Too much emphasis on motives (or justifications, anyway) and the movie can feel more like propaganda than art or entertainment. Too little emphasis, however, and it can feel like whitewashing—like using real suffering for dramatic purposes while evading the toxic ideas and attendant circumstances that brought about that suffering. 22 July—a Netflix original movie directed by Paul Greengrass (Jason Bourne, Captain Phillips, United 93)—resolves this double-bind dilemma by simply opting out of any obligation besides storytelling. Even saying the movie has a “story” is perhaps too “big picture.” It’s really just a series of events. A series of events that happens to begin in tragedy and end in recovery.

22 July starts with Brevik (Anders Danielsen Lie) making explosives then loading them into a van. He’s on a farm. Is it his? Or is he renting it from someone? We aren’t told. All we’re given is what’s happening. The next scene is Viljar (Jonas Strand Gravli) on a boat being taxied to Utøya. He’s laughing with friends. Here’s our first sign that any intentional moral meaning in 22 July will be delivered through cinematography. For while the movie is only events, the juxtaposition between Brevik alone on a farm, sullenly fixated on his horrid plans, with Viljar enjoying himself surrounded by friends, is carefully thought out. In fact, although there aren’t explicit themes in 22 July—themes, after all, being subjective interpretations—there are reoccurring events, and one that keeps reoccurring is Brevik finding himself isolated, both socially and physically. After the massacre his own mother won’t testify in his defense (even though she agrees with him about the state of the world). And when his defense lawyer Geir Lippestad (Jon Øigarden) does find someone to testify—some urbane fascist intellectual who met Brevik through online gaming—the wannabe Goebbels tells the court he isn’t impressed with what Brevik did, nor that he ever thought Brevik showed signs of bravery or was worthy of leadership. That infuriates Brevik, who is slowly realizing how alone—and to his mind unappreciated—he is.

However, if Brevik doesn’t have anyone, he at least has everyone’s attention. He’s obsessed with his right to address the court. That will be when he solidifies his political mission—with the world watching, he’ll condemn immigration and “enforced multiculturalism” and incite his fellow patriots to war. His judge finds no reason why he shouldn’t be permitted to speak which leaves a smirk on his face. (Another reoccurring event in 22 July is Brevik’s mocking satisfaction with the decency and humanism of civilized society.) But when his time comes to speak, he rallies no one and disturbs only a few. He begins his address with a Nazi salute which gets a few court attendees to cover their mouths in revulsion. But most of his ideological claims—and even his personal fanaticism—spark only tiny bolts of discomfort. Brevik wants contempt and outrage and is visibly frustrated when he gets neither.

Besides Brevik, the three other characters we follow are Viljar, Lippestad, and Norway’s prime minister, Jens Stoltenberg (Ola G. Furuseth). On Utøya, Viljar is shot three times by Brevik—once in the thigh, once in the shoulder, and once in the head. Thanks to emergency surgery he lives, but he’ll need physical therapy to relearn basic motor skills, and bullet fragments near his brain stem, too dangerous to remove, could be life-threatening at any moment. His injury-to-recovery-to-testimony is the closest thing 22 July offers as a conventional plot. Lippestad receives death threats for representing Brevik, and he’s forced to remove one of his daughters from daycare because the other parents fear her presence puts their own children in danger. The prime minister is told by the heads of national security that everything that could’ve been done to prevent something like Brevik’s terrorist attack from happening was done; but an independent report reveals that not to be true. Norway’s security attention was too myopically focused on potential Islamic terrorism, leaving Brevik’s suspicious bomb-ingredient purchases detected but ignored. There are obvious interpretations to these scenes, but 22 July won’t make them for you.

As others, including an Utøya survivor, have pointed out, the Norway of 22 July is about as lily-white and male-dominated as Brevik would’ve liked the real Norway to be. There are probably only two or three immigrants seen in the entire movie (or at least only two or three of the kind of immigrants Brevik so hated—i.e., the non-white ones). And the women of 22 July are either background or emotional support for the male leads. This isn’t the sort of thing I’d usually notice, but given Brevik’s ideological hatred for women and immigrants, their absence in 22 July is, well, noticeable.

I watched 22 July with my wife. She’s a good person who has also managed to avoid the moral cesspools of the internet—where men fantasize about raping women or talk of refugees fleeing the death and chaos we unleashed across the Middle East as sinister forces of death and chaos themselves. Where the petty humiliations of life (bosses, medical bills, corporate-speak, addictions, obesity, police-state psychosis, bad education, and shame: physical, mental, and emotional) are exploited by billionaires to turn people against themselves. She cried watching the Utøya-massacre scene: “I don’t understand how anyone could do this…why he hates them so much.” And she’s right: she doesn’t understand. Because to understand bad things requires a familiarity with badness she lacks.

When I think about what Brevik did, about his psychopathology, his moral grotesqueness, I try to imagine what I’d feel if he wrote a different manifesto. One that instead of attacking women, Muslims, and “traitors” attacked his company or bill collectors or the economic system that perpetuates exploitation and dependence. Would I feel any different about him? Would I speak any different about him? Would I say the things the anti-immigrant, anti-PC crowd said in reaction to his terrorist attacks: that actions and motives are separable and distinct? “I don’t condone what he did, but I understand and agree with his frustrations.” Then again, it’s hard to imagine someone angry with their unpayable bills murdering a bunch of children as a political gesture. Targeting a politician? Maybe the bill-collecting company’s CEO? Sure. But children at a summer camp? Even if the children of those politicians and the corporate executives, it’s hard to imagine. Once your mind is consumed by an ideology that tells you the guilty are innocent—that the powerless are powerful—all moral bets are off. We’ve had our own Breviks—men with similar demographics, grievances, and methods. The Oklahoma City bombing. Six dead at a Hindu temple in Wisconsin. Six dead at the University of California Santa Barbara. Nine dead at a South Carolina church. In just the last few days, two dead in Kentucky and eleven dead at a Pittsburgh synagogue. Another two stabbed to death on a Portland train for sticking up for some Muslim women. The perpetrator of that one said afterward, “I’m a patriot, and I hope everyone I stabbed died…that’s what liberalism gets you.” At Utøya, Brevik shouted, “You are going to die today, Marxists.”

Is the lack of context and interpretation in 22 July good or bad? Or, rather, does it work or not? I honestly can’t make up my mind. Politically, it feels a bit cowardly. Like the movie is afraid to speak. On the other hand, perhaps Greenglass is trying to show that the events speak for themselves. Artistically, it has its upsides and downsides. Interpretive detachment leaves a lot of space for emotional intensity and magnification—both of which 22 July has, aided in large part by the brilliant acting. The actors and visuals keep your attention even through the dulling sense of inevitability brought on by the movie’s method of storytelling. But the sense of inevitability is still a distraction. The characters—even Brevik—feel more like witnesses to events than participants. Obviously with based-on-a-true-story movies we usually already know what’s going to happen. But with good ones you still get some sense of agency—some sense that things could’ve been different. Not with 22 July. And without that tension, there is no tragedy. Just a sad story. And what happened on Utøya was more than that.