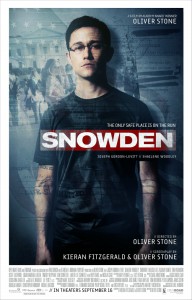

Film Review: Snowden

“Secrecy is security and security is victory.” So says the main antagonist in Oliver Stone’s begrudgingly anticipated political thriller, Snowden. Unsurprisingly, the secrecy he speaks of is not the citizens’ secrecy from their government, but the government’s from its citizens. The security, on the other hand, is for the benefit of both—the government protects its supremacy while citizens are guarded from the shadowed shrieks of terrorism, war, and strife. And to whom the victory belongs—as Stone has always emphasized in his films—depends a great deal on what you think the sides are.

Snowden, based on The Snowden Files: The Inside Story of the World’s Most Wanted Man by Luke Harding and the novel Time of the Octopus by Anatoly Kucherena, chronicles the real-life story of Edward Snowden (Joseph Gordon-Levitt). It’s one that should, by now, be familiar to most. In June 2013, Snowden revealed thousands of classified government documents to journalists Glenn Greenwald (Zachary Quinto) and Ewen MacAskill (Tom Wilkinson) as along with documentary filmmaker Laura Poitras (Melissa Leo). The revelation took place in a Hong Kong hotel room, where Snowden had been cooped up for almost three weeks after leaving his subcontracted job at the National Security Agency facility in Hawaii. Soon afterward, stories ran in the Guardian and the Washington Post exposing the NSA’s massive surveillance apparatus (which included harvesting online content, tracking the location of cell phones, remotely turning on laptop web cameras, and much else).

Days later, the United States Department of Justice charged Snowden with stealing government property and violating the Espionage Act. He eventually escaped to Moscow where he’s been living in exile ever since.

Some say Snowden always intended to stay in Moscow; others believe that the Russian capital was just a layover until he could reach a congenial country in Latin America. The former have convinced themselves that they’ve uncovered a traitor; the latter that they’re defending a saint. However, as the film’s flashback sequences illustrate, neither of these descriptions of Snowden are quite accurate. Instead, we come across a young man who loves his country but is unsure what that love requires of him.

The early flashbacks show Snowden as a conservative by default. He suffers a leg injury that cuts short his training with the Army Reserve, politely dismisses Iraq War protestors outside the White House and is recruited into the CIA’s program for computer specialists. It’s at CIA headquarters where we first meet Snowden’s instructor-cum-professional-mentor Corbin O’Brian (Rhys Ifans) and marginalized intelligence officer Hank Forrester (Nicholas Cage), made-up characters who act as shoulder devil and shoulder angel, respectively, throughout the film. Many other reviewers have already pointed out O’Brian inherits his name from 1984’s villain (although it’s worth noting the two have little else in common).

Snowden meets his girlfriend Lindsay Mills (Shailene Woodley) on an online dating site while in the hospital for his injury, and the two have their first physical interaction when he’s in Washington for the CIA program. Stone makes a monotonous drama out of their relationship, which lacks both romance and passion. All one’s feelings indicate that Lindsay is meant in the film to be a sympathetic character—the relief for Snowden from his high-pressure jobs—but in most scenes she comes off as no more than an upper middle-class, self-consciously bohemian sponger. Besides their apparent willingness to stay in the relationship, it isn’t clear what either has to offer the other.

Snowden eventually becomes disillusioned with his role in the intelligence community. As is most often the case in real life, there’s no identifiable moment where the moral turn precisely happens. Yet there are three moments that, according to Snowden’s own personal recollections, are particularly significant in affecting his change of heart.

The first comes after he’s completed his training on network defenses for the CIA and is stationed in Geneva where he functions as a cybersecurity expert. It’s here where, for the first time, he’s exposed to the far-reach of the NSA’s spy software as well as to the nefarious practices of CIA field agents. For example, an agent Snowden befriends uses NSA-gathered information to manipulate a potentially useful Pakistani banker and, in the process, nearly leads the banker’s daughter to suicide.

A second realization comes during the 2008 election. Snowden briefly becomes hopeful about then-Senator Barack Obama’s run for the presidency, especially his campaign promises to protect whistleblowers and encourage less government spying in online spaces that are believed by users to be at least comparatively private. Once in office, however, President Obama makes few changes to the surveillance apparatus put in place by the prior administration. As Snowden says in the film, “I thought things were going to get better with [Obama]. I was wrong.”

Then, in March of 2013, Director of National Intelligence James Clapper told a Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, while under oath, that the NSA didn’t collect personal data on millions of Americans “wittingly.” But Snowden already knew from his time in Geneva in 2008 that this wasn’t true. The NSA had been using their surveillance programs to collect data on not only terrorist networks (their nominal purpose) but on “the whole kingdom,” as the NSA agent who first shows Snowden the data-collecting programs puts it. Later in the film Snowden discovers that the NSA is spying on more US citizens than on any other country’s.

What motivated Snowden to do what he did should matter little in the general discussion on what he revealed. But despite the best efforts of journalists such as Greenwald and MacAskill, there appears to be no stopping the daily pundits and podcast intellectuals from debasing both themselves and their audiences by chatting endlessly on the doer rather than his deeds. Snowden isn’t guiltless in this matter of course—he’s certainly kept himself busy since avoiding any serious risk of falling into US custody. Then again, knowing what he does about what happens in the shadows, I’d want to stay in the limelight too.

Snowden the film is meant to exonerate Snowden the man, by making known to moviegoers that he didn’t do what he did because he was a disgruntled employee or a Russian agent or a fame-hungry megalomaniac. Stone may have accomplished this but only at the expense of excitement and likely only to those who already concur. A few more subjective fancies in the plot might’ve made the film richer in content, albeit likely at the expense of its important subject matter. Nonetheless, for those myopically fixated on the “motivations” of its namesake, Snowden will be regarded as no more than a propaganda piece. And one already knows the boring motivations behind that.