A Meditation: We Must Grow Past our Inabilities to Learn from History or Accept the Value of Science

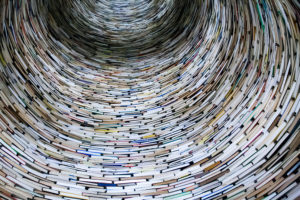

Photo by Lysander Yuen on Unsplash

Photo by Lysander Yuen on Unsplash It was Socrates who noted, “True wisdom comes to each of us when we realize how little we understand about life, ourselves, and the world around us.” Centuries later, French philosopher Denis Diderot would co-author a tree of knowledge that essentially put the concept of “knowing” into a three-tiered taxonomy conditioned by Memory, Reason, and Imagination. It was the work of Descartes, Spinoza, and Leibniz, each playing a major role in the development of rationalist philosophy, and David Hume’s support of skepticism that also helped develop more modern humanist traditions and philosophy.

Today, we might agree or disagree with these and other moral and scientific philosophers. However, their focus on the importance of both reason and knowledge remains steadfast and their work stands in determined opposition in so many discussions today. Sadly, there are too many debates and commentaries that lack an acceptance of rational truth, gleefully misunderstand history, and discredit and disrespect science. Each is forging a diminished public life and endangering public health and safety around the globe.

A huge bomb went off in Nashville in late December 2020. Millions are ill and hundreds of thousands have died due to a terrible pandemic. Racial inequity is systemic. Food insecurity and homelessness are rising. And access to education and the number of people enrolled in higher education is dropping.

Closing yet another year, especially with the mutually agreed awfulness of 2020, usually brings about reflection. In some cases it forces us to review our past ideas, judgments and actions. It may also make us think about how we individually and collectively can improve the future.

Many of us make New Years’ resolutions each year to internally think and externally act better, a version 22.0 or 45.0 or 59.0, depending on our age. Some of us may make end-of-year choices on which charities to support and we may rethink our efforts and our needs in relation to others.

Still, I wonder if that is enough. Perhaps it is because of the pandemic, but I worry that in many instances we are so blinded by the immediate that we lose connection to both the past and the future. Such blindness leads to dangerous ideas and actions that lessen our chance to be humane to one another.

Are we so stymied by the present that we neglect learning about the past? Or are we so consumed by the present that we cannot collectively imagine a positive future? And why, for instance, is science and expertise viewed by many with suspicion or as a threat?

Doesn’t rational truth sustain us better than magical thinking? While the acceptance of ideas without evidence or proof are suitable and even lauded by faith-based communities, how and why did this spill over into conspiracy-laden politics? What has happened to the idea that obtaining and accumulating unbiased knowledge is a social good?

In every generation we find the majority of people are caught up in the politics and economics of the day. People are swayed by the media or indulge in gossip, or use technologies that appear to make life livable but in fact eliminate both connection and compassion. We humans most often live in “the now” and, if we do plan at all, it’s usually for the very immediate future.

For the majority of our species, “the now” offers both the comfort and the standard to which we attempt to understand and live through our life experiences and present selves. It takes a large amount of time and energy to truly understand the past and work on exploring or creating the far future.

Perhaps the way we’ve structured society leaves little energy or time for the majority of our species to contemplate or truly understand the implications of our history and our future?

From an evolutionary perspective, if everyone spent time summarizing the past or attempting to invent the future, few of us would be working on the immediate problems in the present. That could indeed stop us, almost ironically, from knowing the past and preparing for the future. Also ironically, I might add that our present problems are usually the result of decisions or actions created FOR US because of actions taken BY US.

In essence we may be doomed to be a species that tends to give the gift of knowledge and reason in equal proportion to our creation of situations that sustain our ignorance. But I will touch more on this later.

Humans left collective life behind many thousands of years ago. Both biological and social evolution has allowed us to live more complex lives by stratifying our societies. Simply put, stratification allows a few to work in areas that benefit the many or the whole. The world changed dramatically once we began farming and domesticating wild plants and animals. The move from band life to staying put and laying stakes, to changing whole geographies for generations to follow, allowed our ancestors and their social world to change and adapt dramatically.

But stratification, like all human creations, provides its own double-edged sword. It allowed us to compartmentalize our cultural ideas, our biases, our responsibilities to each other, our duties and our modes of living. It also meant that individuals can leave the past and the future to others to understand, create, or solve. It ultimately allows an ever-smaller group of experts to process and organize knowledge, making the rest of us end-users of their activities and imaginations.

Essentially, our modern world, which began as baby steps thousands of years ago, allows the majority of us now to take great beneficial leaps while remaining ill-informed, and sometimes even hostile, to our past and future.

For those who specialize in understanding the past or who work on advancing our future, the burden to inform the large middle of their efforts, certainly benefits global civilization, even if the many ignore, or mindlessly adopt the information being provided.

But at the same time such complexity and stratification puts distance between knowledge and living. It places a wedge by allowing the majority of us to remain deeply intellectually impotent while our ability to grow our knowledge and discovery increases dramatically. Ignorance at this level is very dangerous, especially since we’ve developed significant gaps in the way we educate the whole. We’ve built these elaborate complex global communication systems only for them to be used to push propaganda, tell outright lies about people and events, and serve as a stream for manipulation of the masses.

So many of our current problems are ones that have plagued past civilizations, yet we don’t recognize them in our own time simply because we’re lost in the confines of our present. We allow our modern politics and our current theological perspectives to invade our classrooms and public spaces.

The result is the dimming of the efforts by those who research and teach the past and the future for the sake of illusionary ideas of “religious freedom.” Religious ideas, more properly taught in philosophy or history classes, have no bearing or place in biology labs or science classrooms.

A religious symbol on a public space, the denial of legal rights to reproductive freedom and marriage equality due to religious objection, is not religious freedom. It is religious preference over the legal rights of others.

Let’s not forget to give credence to so many other social ills that humans have tirelessly recreated against other humans. Certainly when we cannot feed ourselves or our families, pay the rent, buy medicine, find a job, if we live in fear of reprisal or we cannot educate our children, learning about the past or planning for the future gives little relief from the physical problems and realities of the present.

How can we teach the past while at the same time create a collective future when so many people feel impotent in the present? When many choose to blame immigrants or weaker others for their plight? How do we move from these ingrained feelings of tribalism based on nationalism, race, religion, ethnicity, and socio-economics so that we can expand the definition of “tribe” to include each and every one of us on the planet?

One of my favorite educators of science, Dr. Carl Sagan, once said, “If you want to make an apple pie from scratch you must first invent the universe.”

The suggestion here is that we must acknowledge that our ability to bake and consume an apple pie comes from an understanding of where the apples ultimately came from. How we evolved the ability to prepare, cook and eat the pie. And, if we are humane enough, how we need to preserve these ideas so our children and their children can bake their own apple pies.

In order to make science and history truly relevant, meaningful, and enjoyable we’ll need to get rid of our baggage to better engage every one of us. We’ll need to decide to put fair, accurate and accessible economic policies in place. To fund and ensure safety nets exist that will allow for living wages, and well-maintained healthcare and education systems. We’ll need environmental policies that do not destroy, but sustain our planet.

We’ll also need to abandon the concept of “the other” once and for all by placing the idea into the dustbin of human history for the sake of a better human future. We’ll need to understand that stratification in every economic and political system must be balanced by the needs of the many rather than the needs of the few.

We’ll need to put religion into the confines of human imagination rather than view it as a non-scientific form of attainable, testable and verifiable truth. Further we’ll need to ensure no one is homeless, support those with mental illness, and find ways to guarantee that no person is ever food insecure.

If you want to have an adroit and powerful global consciousness that respects science, the universe, and our collective history, then we must create it based on humanistic good will towards all. If we want the flame of youth to be invigorated equally by the past and also the possibilities of the future then we must give our students the time and space they need to develop their individual interests in the arts, humanities, and the sciences.

So here is how I suggest we must move forward. The conundrum rests in these five points as follows:

- If we can give the time and energy necessary to grow our human connections we can limit tribalism and hostile stratification. We can empower a global humanity of thinkers and builders

- If we’re willing to give the time and space to douse the willful assumption that there must be social and economic winners and losers in this world, we can move past despair and bring hope to generations.

- If we can give time and opportunity to remove fears or stigma of facts, which always subverts understanding of the natural world and breeds mistrust of those who bring knowledge forward, then we can educate and prepare the globe for a bright and intellectually robust future.

- If we can give time and energy to understand our past through reason and knowledge based on evidence rather than conjecture or self-serving bias, we won’t be afraid to confront our past ills and we certainly won’t bring pain and suffering to others in the future.

- If we can give time and energy to fully understand how technology works to sustain and improve our lives, it is unlikely we will use that same technology to harm ourselves. We will then combine our imagination, our will and our tools to fully explore our planet and worlds way beyond our present grasp.

It’s a large task, but no doubt one we can undertake. Together, we can understand and respect the past while also embracing science, technology and the future.