America’s Forty-Year Wealth Transfer: A Humanist Reflection on Debt, Power and the Vanishing Middle Class

Once upon a time, in 1981, America decided to run an experiment on itself.

Not a scientific experiment with controls and ethics committees, but the other kind, the kind where a nation trusts a story because it feels good.

We were told that if we cut taxes for the rich, deregulated everything with a pulse (and a few things without one), and offered a heartfelt prayer to the invisible hand, prosperity would trickle down to everyone else.

Forty years later, the only thing trickling down is existential dread.

Today, the top 1% holds about fifty-four trillion dollars, enough to buy a medium-sized country and still have plenty left over for several senators and a decent chunk of the House. Meanwhile, the federal government owes thirty-eight trillion dollars. In a humanist sense, these numbers are not merely economic statistics. They are moral accounting. They are the debits and credits of a society that quietly redefined what counts as virtue.

We did not lose thirty-eight trillion dollars.

We gave it away.

The federal deficit, it turns out, is the invoice for the 1%’s tax cuts.

The Gospel According to Ronald

Ronald Reagan, Hollywood’s most successful method actor, delivered a story Americans were eager to hear. Government was the problem, taxes were the chains, and freedom meant cutting them loose. It was political theater with biblical overtones, and we applauded because the script felt righteous.

The top marginal tax rate fell from 70% to 28%. Investment was supposed to soar, jobs were supposed to blossom and deficits were supposed to evaporate through sheer optimism.Instead, the deficit tripled, middle-class wages stagnated and Wall Street threw a party that has not ended to this day.

Reagan did not shrink government. He changed who it served. The beneficiaries were not citizens but shareholders. Not communities but corporations. Not the public good but private accumulation. Yet the rhetoric treated higher taxes on billionaires than nurses as a moral scandal, as if progressive taxation were a cosmic mistake.

The Vanishing Middle, A Humanist Autopsy

Before this grand experiment, the American middle class was imperfect but functional. A single job, milkman, gas station attendant, librarian, retail clerk, bank teller, could support a family, buy a house, send a child to college and maybe even fund the occasional vacation.

The federal debt was modest and shrinking relative to the economy. More importantly, the benefits of growth were broadly shared. It was not utopia, but it worked. And in humanist ethics, functional fairness often beats theoretical perfection.

Then the new tax ethos arrived. Relief for the wealthy, precarity for everyone else. Real wages froze. Housing, healthcare and tuition inflated like parade balloons drifting into low orbit.

But the deepest change was cultural. Corporate America adopted a new theology.

CEO pay became tied to shareholder value, a serene euphemism for stock price at the moment executives cashed out. To raise that value, companies cut benefits, froze wages, outsourced jobs and right-sized entire communities. It worked brilliantly for the people measuring success, and disastrously for the people producing it.

A new moral code emerged: sacrifice the worker to please the market and call it efficiency.

The Reagan years did not simply redistribute money. They redistributed security, dignity and belonging, the core goods of any humanist society. They replaced shared prosperity with debt, credit cards, and nostalgia for a past that tax cuts quietly dismantled.

By the 1990s, the milkman was gone, the gas station attendant was part-time with no benefits, and the librarian had become a renter in the town where she once shelved books. The American Dream did not collapse. It was quietly euthanized by quarterly earnings reports.

Today, that dream is inverted. Hundreds of thousands of full-time workers at companies like Walmart, Amazon and McDonald’s rely on food stamps, Medicaid or housing assistance while their employers post tens of billions in profits. In 2023, Walmart alone cost taxpayers an estimated five billion dollars in public aid for its employees. McDonald’s workers qualify for the same public programs its lobbyists try to shrink. Amazon perfected the model: warehouse workers on government-subsidized healthcare while Jeff Bezos inspects a yacht that has its own yacht.

This is not an economy. It is a transfer of obligation from corporations to taxpayers, a privatizing of profit and a socializing of poverty.

Creeping Normalcy, A Slow Moral Collapse

The insidiousness of all this lies in its gradualism. Philosophers call it creeping normalcy, the slow drift of the unacceptable into the routine. Each decade, the middle class lost a little more, a trimmed pension here, a higher mortgage there, a benefit quietly removed.

But life still felt normal. We had televisions, microwaves, cars, credit cards, streaming services and phones that were smarter than the people programming them. Comfort disguised decline.

By the time the damage was visible, it had become ordinary.

Human psychology did the rest. People clung to beliefs not because they were true, but because changing them would require admitting they had been misled. Trickle-down economics ceased being a policy and became an identity.

Challenging it felt like heresy.

And so the country adapted. We called debt freedom. We called precarity opportunity. We called corporate servitude the gig economy. The middle class did not just lose ground. It lost the vocabulary to describe what happened.

The Illusion of Shared Prosperity

Reaganomics worked for one simple reason. Everyone thought they were winning.

If you earned one hundred thousand dollars, you might have saved six thousand in taxes, enough for a new television, a larger SUV, and the impression that government was finally letting you keep your money.

But if you earned ten million dollars, those same tax cuts handed you about five million in savings every year. Add in capital gains tax breaks and stock options, and you were not buying televisions. You were buying senators.

The middle class received a modest raise. The wealthy received a wealth transfer.

The genius of trickle-down was not its math. It was its marketing.

The Mechanism of the Heist

Why does a drop in top marginal tax rates from 70% to 28% mostly affect the ultra-rich? Because only the ultra-rich ever lived in that bracket. Middle-class workers were never paying 70% marginal tax rates. You could sell your house, your car, your kidney and your soul, and you would still not get anywhere near the top bracket. Marginal tax brackets apply only to income above a certain level, and in the 1970s that level was so stratospheric that only CEOs, movie stars, oil tycoons and people who had recently discovered a diamond mine in their backyard qualified. When the top rate fell, the teacher did not get a windfall. The milkman did not get a windfall. The librarian did not suddenly shout, “Zeus! My ship has come in!” The only people affected were those earning sums big enough to influence the tides. In other words, the cut from 70% to 28% was not a tax break for America. It was a tax break for the people who own America.

The drop from 70% to 28% on top earners was not a reform. It was a lever. When it was pulled, trillions of dollars gushed out of public budgets and into private portfolios.

But the money did not travel through a single pipe. It flowed through a labyrinth of loopholes, subsidies, defense contracts, accelerated depreciation schedules, real estate shelters, carried interest provisions, and stock buybacks. The transfer of wealth became an ecosystem. The process was simple in theory and elaborate in practice.

- Cut taxes for the wealthy and corporations.

- Create a revenue hole.

- Borrow money to fill that hole.

- The wealthy use their untaxed gains to buy Treasury bonds or other assets.

- The government pays them interest while their investments inflate asset prices.

It is like robbing a bank, then lending the bank its own money back, with interest.

The wealthy did not just avoid paying their share. They got the government to borrow from them and reward them for the privilege. What the middle class saw as patriotic savings bonds for grandma’s retirement were, in reality, a perpetual-motion machine of wealth extraction.

When rich people get money, they do not spend it on goods or wages that circulate through the economy. They park it in investments that make more money. Their dollars do not move; they pool. Each tax cut created more money chasing the same assets, driving bubbles, speculation and inequality.

So while the rich were compounding wealth through passive income and capital gains, the middle class was stuck borrowing to survive and then taxed to pay interest on the debt that made the rich richer.

We call it “deficit spending.” They call it “passive income.”

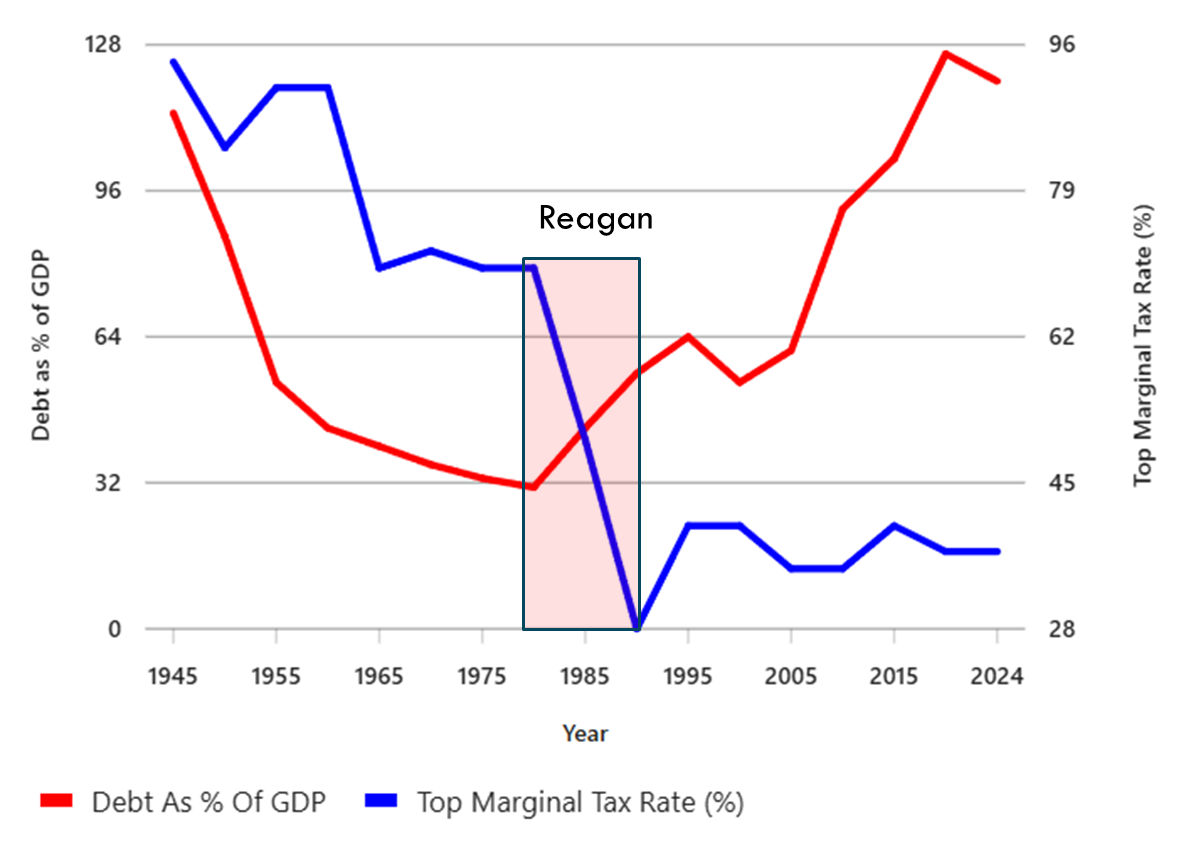

Figure 1. Federal Debt and Top Marginal Tax Rate, 1945–2025

In 1980, before Reagan’s experiment began, the top 1% owned about $6 trillion, adjusted for inflation, while the national debt stood at $900 billion.

Today, those numbers stand at $54 trillion for the 1% and $38 trillion for the Federal debt. The two curves rise together, locked in a waltz of redistribution: public debt swelling in perfect proportion to private wealth.

This is not coincidence; it is arithmetic. Every dollar the government did not collect in taxes became another dollar borrowed, invested and compounded by the ultra-wealthy.

Reagan did not trickle prosperity down; he siphoned it up.

What Would a Conservative Say?

A conservative might sigh and say, here comes another liberal jealous of success.

They would insist billionaires are not greedy but efficient. They would praise Elon Musk, Steve Jobs and Warren Buffett as visionary geniuses who earned every penny and deserve to be centibillionaires because they create value, even if that value seems to be apps that show ads to other billionaires.

They would argue that tax cuts do not cause deficits. Spending does. If only we cut school lunches, the economy would flourish.

They would explain that the rich invest their money. They do, into stocks, luxury real estate, and hedge funds, not into the milkman revival project.

They would warn that taxing the rich punishes success, as if billionaires were hothouse orchids who might wilt if asked to help pay for bridges.

They believe wealth is proof of virtue. The economy is a scoreboard. If they win, the rules must be fair.

They do not think this is a heist. They think it is natural selection with better suits.

Do We Really Need Centibillionaires?

This essay does not call for communism. It just suggests a modest reform: maybe centibillionaires could be gently downgraded to mere billionaires.

Let us be honest, how different is the life of someone worth $100 billion from someone worth $1 billion? Both can buy a fleet of yachts, own several islands and send rockets into space just to feel something. At that level, money stops being useful and starts being a scoreboard for sociopaths.

A billionaire can live anywhere, buy anything and fund their wildest whims for ten lifetimes. A centibillionaire can do all that and also distort democracy. That extra ninety-nine billion is not for comfort; it is for control. It buys senators, your own mass media, algorithms and narratives.

The average American’s “net worth” is their car and a 30-year mortgage. Meanwhile, a handful of centibillionaires could end homelessness before lunch and still have enough left to buy every beachfront property on the planet. But they will not end homelessness, because the point of extreme wealth is not having things, it is having everyone else not have them.

There is no moral or economic justification for anyone to hoard a hundred billion dollars. That isn’t capitalism. It’s aristocracy by another name.

The Moral Ledger

The national debt is not just a number. It is a ledger of who got paid.

We could have used those trillions to fund public goods: education, infrastructure, renewable energy, healthcare. Instead, we turned them into private jets, speculative assets and high-frequency trading algorithms that treat the economy like a slot machine.

Every Treasury bond represents a promise that future taxpayers will pay today’s billionaires for yesterday’s tax cuts.

And when politicians talk about balancing the budget, they do not mean collecting from those who gained. They mean cutting Social Security, Medicare, and anything that smells like shared prosperity.

We did not make a fiscal mistake. We made a moral one.

The Inheritance No One Wanted

The national debt does not die with us. It is passed down like a toxic heirloom.

The United States now spends about one trillion dollars annually on interest payments, more than on Medicare or defense. Future generations will pay higher taxes for fewer services, live in a country with declining infrastructure and face asset prices inflated by a system they never agreed to.

When billionaires avoid taxes, the burden shifts to people who are not even old enough to vote.

Our children will inherit interest payments, not opportunity.

The MMT Mirage

Modern Monetary Theory says the government can print its own money. True, but incomplete.

MMT was designed for emergencies, not to normalize forty years of enrichment for the wealthy. It was created to stabilize economies with unused capacity or crisis-level unemployment. It was not created to justify permanent tax cuts for billionaires.

Printing money erodes purchasing power and shifts costs from taxpayers to consumers. Used recklessly, it becomes a way to hide the wound instead of healing it.

If MMT were a fire extinguisher, policymakers are now using it as a flamethrower.

The Reckoning

Fixing this requires courage, not austerity.

• Restore higher marginal tax rates on extreme wealth.

• Tax capital gains like ordinary income.

• Close loopholes that let billionaires borrow against assets tax-free.

• Treat inheritance as unearned income.

The solution is accountability.

The Final Joke

Reagan promised a shining city on a hill. What we got was a gated community with armed guards and a helipad.

After forty years of trickle-down, the only thing that trickled was our wealth, and it trickled uphill.

The federal debt is not a mystery. It is the receipt.

America did not go broke. We simply made the rich whole and sent ourselves the bill.

References and Data Sources

- Federal Reserve Distributional Financial Accounts (DFA), 2024: Top 1% wealth estimate, Q2 2024, approx. $54 trillion.

- U.S. Department of the Treasury – Fiscal Data: “Debt to the Penny,” Sept 2024, total public debt ≈ $38 trillion.

- Congressional Budget Office (CBO) Historical Tables: Federal debt as % of GDP, 1945–2024.

- Internal Revenue Service (IRS) Statistics of Income: Historical top marginal income tax rates, 1945–2024.

- Office of Management and Budget (OMB) Historical Tables 1.1, 2.1, and 7.1: Federal receipts, outlays, and deficits.

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS): Median real wages, CPI-U inflation adjustments.

- U.S. Treasury FiscalData Portal: “Interest Expense on the Debt Outstanding,” FY 2024 ≈ $1 trillion.

- Economic Policy Institute: CEO-to-worker pay ratios, wage stagnation analyses.

- Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP): Analyses of corporate effective tax rates post-1980.