Dirty Americana, Rock ‘n’ Roll Heretics

Photo by Ahmed Rizkhaan on Unsplash

Photo by Ahmed Rizkhaan on Unsplash Picture this: a blond white woman wearing a black tank top and playing a white electric guitar graces the title page of Music Radar’s recent article shouting out the ten leading blues guitar players in the world. No Black women merited inclusion on the list. Not blues powerhouse Ruthie Foster; not mega-talent shredder Malina Moye. Only three Black men scored. In this universe, the blues long ago left the building as a uniquely African-American art form steeped in the poetry of secular lamentation, Black struggle, and irreverence.

It’s no revelation that “eating the other” (to use bell hooks’s term) is as Americana as apple pie and mass deportations. In the funhouse mirror of twenty-first century minstrelsy, white folks rule blues and rock, white rap hipsters have become yawningly pro forma, and white women hawking border chic in flavor-of-the-month novels like American Dirt are anointed to speak for the brown downtrodden.

Like many women of color who are writers, I was outraged when I heard about the gushing adulation, Oprah Book Club endorsement, and obscene payday that American Dirt writer Jeanine Cummins received for her fetishized portrait of Mexican immigrant life. Shutting down the Cummins’ hype machine, Latinx writers Myriam Gurba and Esmeralda Bermudez dubbed the book an empty narco-thriller that trotted out racist, sexist stereotypes about Mexican immigrant communities for the white gaze. The organized backlash against Cummins was a rare instance when the longstanding grievances of women of color about white supremacy in the literary establishment had swift, national repercussions. Cummins’ book tour was cancelled, and Latinx writers from the #DignidadLiteraria group reportedly got her publisher to commit to increasing Latinx staff representation as well as book acquisitions. Some in the media attempted to portray Cummins as the victim of angry Latinas with pitchforks. Her wounded chagrin was reminiscent of the white fragility sweepstakes which arose after author Kathryn Stockett was slammed by Black writers about her Mammy-splaining novel, The Help. In that instance, white gatekeepers wasted no time securing film rights and bankrolling a movie that showcased the pride of Miss Ann’s Hollywood lording over noble Negroes in a deep Jim Crow South notably devoid of civil rights activists.

When Black, Latinx, indigenous, and Asian novelists and fiction writers scrape to get by, shrug off rejection after rejection, and see white folks get outsized acclaim for writing about communities of color, it confirms that nothing has changed in literary plantation politics. It’s estimated that nearly 80 percent of publishers are white, and that the majority of acquisitions editors are white women (most of whom probably fall all over themselves to denounce Trump). This divide between liberal window dressing and the reality of plantation lit politics is underscored by publishing’s neoliberal bottom line. As poet Shivana Sookdeo notes,

Without support for the marginalized already within publishing, from living wages to protection from backlash, you can’t attract more. Without that growth of the workforce, you can’t effectively safeguard against exploitative works. Without those safeguards, you make it even more inhospitable for diverse talent. Then you’re back at square one, publishing establishment, safe, whiter voices because the entire chain has been neglected.

So who shells out crazy ducats for the Black gaze on white America?

So who shells out crazy ducats for the Black gaze on white America?

Picture this: decades after her death at twenty-seven from a drug overdose, the legacy of Janis Joplin still looms Godzilla-large over women’s history in rock music. Joplin was the first white woman musical colonist to ride her ear-bleeding, angsty rip-offs of Black blues standards to big bucks, stardom, and notoriety. Post-crash and burn, Joplin has been the subject of umpteen biopics, documentaries, books (a new biography just dropped in October), musicals, and gushing odes to her own peculiar brand of parasitic white woman alchemy. While Joplin’s cottage industry rolls on, only recently have the queer Black pioneers Joplin stole from—rock and blues musicians like Bessie Smith, Ma Rainey, and Rosetta Tharpe—received mainstream recognition for their trailblazing impact on American music.

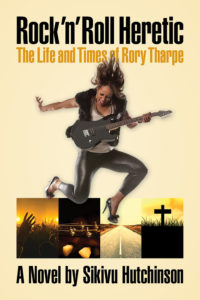

I started writing my long-delayed but forthcoming novel, Rock ‘n’ Roll Heretic: The Life and Times of Rory Tharpe, out of my lifelong ride-or-die love for all types of rock music (from Son House to Rosetta Tharpe to Memphis Minnie to Band of Gypsys to Sonic Youth to Neil Young to Jimi Hendrix to Arthur Lee to PJ Harvey to Parliament/Funkadelic to King Crimson to Malina Moye to Brittany Howard). I was equally motivated by the desire to explore the theft of Black creativity by corporate America and the fact that the lived experience of working, Black female musicians is rarely captured in fiction.

Malina Moye (holding guitar) at the Women’s Leadership Project’s Future of Feminism conference in 2018 (photo by Zorrie Petrus).

One of the novel’s central themes centers around the artistic travails of Black women rendered invisible by the genre’s association with alpha-male whiteness in the post-British invasion era. I wanted to explore the everyday challenges, failures, and quiet triumphs of being a Black female guitarist on the road playing dive bars and middling concert halls and the day-to-day grind of trying to keep a band together and the bills paid. Loosely based on Rosetta Tharpe—a gospel guitar titan of the 1930s and 1940s criticized for embracing secular rock, blues, and country music—my protagonist grapples with the PTSD of sexual abuse; sexist and racist discrimination by record labels, promoters, and managers; and getting old in a youth-driven 1970s pop music culture. Fronting a band of men, she navigates a cutthroat record industry that chews up and spits out Black musicians who don’t fit neatly into accepted radio formats and hyper-feminized marketing images that appeal to white consumers. Like Rosetta Tharpe, Rory is a queer musician in a notoriously homophobic, testosterone-driven world. She’s also losing faith in God amidst a wave of prosperity gospel and Black evangelicalism. She comes into conflict with a Joplinesque white artist who tries to capitalize on Rory’s outlier status to add street cred “spice” to her own career.

The novel allowed me to explore a number of central questions about female creativity within the context of extreme generational and religious trauma. For example, how do Black female musicians maintain their self-determination in shark-infested professional waters? What role do women’s ambivalent desires play in forging complicated, often toxic artistic relationships? How did older Black women push back against a multibillion-dollar industry that sucked up Black ingenuity while deifying white male rock “gods”? And, finally, how do Black women artists navigate depression, as well as persistent thoughts of death and dying, when they’re expected to buck up and be self-sacrificing superwomen?

Many fiction writers who are women of color know this syndrome all too well. Writing outlier fiction—often in a snarling void, often pushing up a Sisyphean hill of preconceived, reductive notions about the Black imagination—is a tightrope walk. After years of rejections, deflections, games, and crickets from the publishing industry, I self-publish most of my books. I can’t wait for the literary gatekeepers to give my voice “permission” or validation. As Alice Walker once said, “I write not only what I want to read, but I write the things that I should have been able to read.” I write for Black girls on a mad quest fueled by wanderlust, looking for signs of themselves in the heart of dirty Americana.