Happy Twentieth!

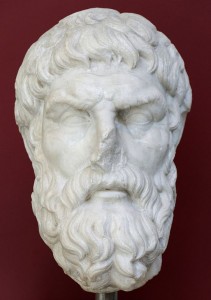

Roman bust of Epicurus

Roman bust of Epicurus While reading Stephen Greenblatt’s award-winning book, The Swerve, three years ago, I stumbled on a delightful fact. It seems that devotees of the Greek philosopher Epicurus, for hundreds of years after his death, continued to celebrate his birthday. Not just once a year, as people observe birthdays nowadays, but every month. Epicurus was born on the twentieth day of the Greek equivalent of January, and on the twentieth day of every month of the year his fans would get together to open a wineskin, share a meal, and, most importantly, enjoy each other’s company.

I’m generally a little slow on the uptake, but for once I was seized by an inspiration. I could do that too! Ever since then, I’ve been a zealous observer of the Twentieth, making me part of a small but growing band of “Twentiers.”

The rationale for celebrating often is central to the Epicurean ideal. Epicurus taught that if there actually were any gods, they were so far above humankind as to not really care about us, any more than most humans care about individual ants. So, Epicurus’s reasoning goes, we’re on our own, and since there’s no point in attempting to cater to uncaring gods, the most we can hope for is to be happy. What exactly “being happy” entailed was of intense interest to Epicurus and his students, who gave the question a great deal of disciplined thought.

What they concluded was far removed from today’s dictionary definition of Epicurean as “fond of or adapted to luxury or indulgence in sensual pleasures.” On the contrary, Epicurus encouraged keeping your desires as simple as possible, thereby making them easier to satisfy. (Long before learning anything about Epicurus, I determined to avoid developing a taste for expensive beer, wine, or coffee; I’ve had an easier and happier life as a result.) After comparing and contrasting all the different forms of happiness (a pleasant pastime in and of itself), Epicurus and his followers decided that the greatest happiness of all was found in the simple act of communing with friends. There are probably some deep psychological and evolution-driven reasons for this that surpass my understanding; but if you search your own soul, I doubt you can come up with any activity that more consistently produces true happiness than good conversation with good friends.

This result was especially meaningful for me, because, to put it bluntly, I have never been especially outgoing. My idea of a good time is an afternoon in the Library of Congress, or watching a soccer match, or an old movie. I steadfastly refuse to attend Super Bowl parties because I don’t like people yakking through a game I’m trying to watch. I’m not knocking social butterflies, but that just isn’t me. It takes a good kick in the butt to get me off my inertia, which is exactly what every upcoming Twentieth now provides. Every month, I’m forced to ransack my contacts list, seeking a name of an old friend I haven’t seen in a long time, or a new acquaintance it might be interesting to get to know better.

“Hey, remember me? How would you like to participate in a pagan religious ritual? No burnt sacrifices, just a nice dinner where we can catch up.” This month, my wife and I will be getting together with a former neighbor whose children I coached in soccer for several years. Were it not for the self-imposed pressure to come up with a Twentieth date once a month, every month, the likelihood that I would have reached out to this person would be zero. But now I can’t wait to see her.

Not all our Twentieths have involved dinners. Sometimes there’s a gallery exhibit, an outdoor excursion, a ballet, a train trip, or a sporting event involved. The key element, though, is that it’s not just me and my spouse. There has to be a connection with other people; otherwise, the whole point of the exercise is missed.

The biggest thing organized religion has going for it is the community it provides. There are humanist organizations that have met regularly for years, and now there is an atheist “Sunday Assembly” gaining some traction. More power to them, but for the congenitally lazy like me, committing to a regular group that doesn’t even promise eternal salvation just isn’t going to work. I can, though, commit to connecting with another human once a month, and I’m grateful to old Epicurus for having a birthday that gives me a most excellent motivation and excuse to do so.