Jeffrey Epstein and the Movement of the Planets

AI-generated illustration via author Noah Kennedy.

AI-generated illustration via author Noah Kennedy. This article first appeared on author Noah Kennedy’s website here.

Stuck at a stoplight recently, I was directed by a tattered bumper sticker to “Subvert the Dominant Paradigm.” I could just make out the back of the driver’s head in front of me, who presumably had made the effort some time ago to install this message onto his car so that he could share it wherever he went. He was sitting alone, seemingly lost in his own thoughts. I wondered which dominant paradigm he had in mind to subvert, and whether or not I would agree that particular paradigm indeed had to go.

This bumper sticker exhortation – and in fact the very idea that there is such a thing as a dominant paradigm, is a distillation of a profound and still relatively new idea. It comes from a landmark book that was published in 1962, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions by Thomas Kuhn. We tend to think of scientific knowledge as a neat process in which new ideas build on top of previously-established concepts like building blocks. This, it is commonly believed, is the straightforward way the massive and ever-growing edifice of scientific knowledge is built.

But Kuhn, citing numerous historical examples, articulates that the way it really works is messier and far more interesting. He shows that, time and again, new observations and ideas are indeed built on top of already-established ideas—what he called “dominant paradigms.” But invariably, as the dominant paradigm is forced to accommodate more and more observations, logical difficulties emerge that the paradigm can’t explain. Ultimately the dominant paradigm, and all the secondary ideas that depended upon it, has to be jettisoned so that a new, more promising paradigm can take its place.

The historical pattern can be seen again and again. The difficulties of the dominant paradigm initially appear minor, and most scientists consider it their task to tweak the conventional wisdom to accommodate the inconsistent data. But eventually, as more ideas and observations are made to fit on a faulty foundation, the logical contradictions become so obvious that a period of confusion and controversy sets in among the leading thinkers in a given field. This causes a literal crisis of understanding, until finally, the old foundational ideas have to be shoved aside, toppling the secondary theories that depended on them. This brings about scientific revolutions, or what Kuhn characterized as “paradigm shifts.”

Kuhn concludes that science, and knowledge of the real world in general, is not the straightforward construction of an edifice of knowledge as much as it is the ongoing construction of some ideas and the dramatic dismantling of others. Tentative progress, punctuated by disruptive backtracking, followed by additional tentative progress. The mystery is how to know when and where to keep building on what you think you know, versus when and where to tear it all down and start fresh.

There is a creepy aspect to Kuhn’s theory if you read it carefully. Kuhn is not writing about how scientists discover the truth, but rather how they come to agree on what the truth is. He doesn’t view science as inherently different from any other human undertaking that relies on understanding the world. Thus, Kuhn’s focus is not on “truth,” but instead on how consensus develops within communities, in this case communities of scientists.

He also discusses what happens within a community when the dominant paradigm begins to fail: the increasingly desperate attempts to make the failing paradigm work, the bitter arguments among former allies, and the emergence of new champions as a new dominant paradigm struggles to take shape.

And that, if you’ll stick with me, will bring us around to the current case of Jeffrey Epstein.

The Example of the Copernican Revolution

The Structure of Scientific Revolutions became a touchstone in the philosophy of science, a dramatic example itself of the paradigm shifts it describes. But you can see Kuhn grappling with his central ideas in an earlier and, in many ways, more intriguing work. In 1957, he produced The Copernican Revolution: Planetary Astronomy in the Development of Western Thought. The book is a deeply-researched history of the most famous of all paradigm shifts: the idea that the earth orbits around the sun, rather than the more intuitively appealing but false idea that the sun is moving around the earth. The medieval figure who brought things to a head was a sixteenth-century astronomer and cleric named Nicolaus Copernicus.

Many people think they know the outlines of what happened: that Copernicus was clearly correct, but that he was silenced by a narrow-minded Church hierarchy. It is true that the Church had attached itself to the idea that the Earth (and, by extension, “Man”) must be the center of the universe. The Roman Catholic bishops were inspired by references in the Bible that indicated the sun was moving around a fixed earth. This idea played well with their own self-serving ideology, and they took the position that it was heresy to claim the earth revolved around the sun. Another plus for the idea of an earth-centered paradigm was that it was associated with the ancient writings of Ptolemy of Alexandria, and so it was imbued with the prestige of classical wisdom.

It took time, but after he died, Copernicus came to be remembered for subverting the dominant paradigm of his era. Thus, the Copernican Revolution is commonly remembered as a simplistic morality tale in which courageous, open-minded science triumphed over a dogmatic attachment to traditional thinking.

But Kuhn highlights an aspect of this medieval debate that many have forgotten. In Copernicus’ lifetime, if you were an astronomer tasked with predicting where Jupiter or Venus would appear on a given night, you would have been better off relying on the Ptolemaic system—the very paradigm we know now was fundamentally wrong—than on Copernicus’s model, which we know today was basically correct but incomplete. The Church did indeed play a role in holding Copernicus’s theory back, but the fact that Copernicus’s theory didn’t “work” as well as the traditional Ptolemaic paradigm had a lot to do with why so many contemporaries rejected it.

Looking back on it now, we can see that Ptolemy’s earth-centered model could be made to work, given the proper motivation and sufficient creative thinking, and so it was.

The mathematicians who elaborated upon Ptolemy’s model to make the movement of the planets conform with real-world observations thought they were reasoning through a problem to get to the truth, when what they were actually doing was rationalizing what they were seeing so that it fit their way of thinking. They were building on what they thought they knew when they should have been tearing down and starting over.

The Problem of the Planets

The movement of the sun, moon, and stars was easy to explain in both a geocentric (Ptolemaic) or heliocentric (Copernican) model, but the confounding issue for Ptolemy and Copernicus and all the thinkers before them was the movement of the planets.

The term “planet” derives from the ancient Greek word for “wanderer,” reflecting the odd way the planets seemed to move around the nighttime sky. The ancients could plainly see that most stars marched across the sky in fixed, unchanging formations, as if glued to the inside of a rotating sphere with the earth at its center. But the planets wandered around within this field of stars in ways that were devilishly difficult to predict. Though they generally followed along with the sweep of the stars in the heavenly vault, moving east to west, they sometimes moved faster, and sometimes slower, than the stars around them. Occasionally, the planets even seemed to reverse course entirely, a movement known as “retrograde motion.”

To ancient observers, this was a deeply mysterious phenomenon that evoked all sorts of mystical interpretations, including the sense that the planets had some sort of agency in human events. An astrologer would counsel that “Mars retrograde” was a signal to reassess one’s initiatives, and that “Venus retrograde” meant it was time for you to reflect on your personal relationships. That ancient thinkers like Ptolemy sought a rational, rather than a mystical, explanation for retrograde motion was itself a bold advance in scientific thinking.

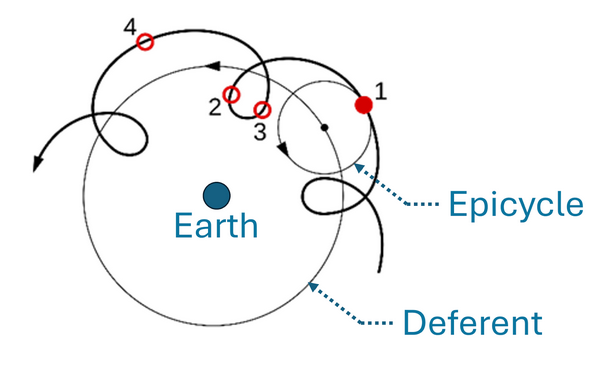

Ptolemy assumed the Earth was the center of the universe and that the sun, moon, planets and stars circled around it. To explain the planets’ abnormal behavior, Ptolemy stuck to the prevailing paradigm at the time that the planets also circled the Earth, but in their own idiosyncratic way. Rather than circling the Earth like the other heavenly bodies, ancient Greeks postulated that the planets were circling a point that was circling the Earth. The larger circle that this point followed around the Earth he called the deferent, Greek for “conveyor,” and the smaller circle the planet followed around the imagined point he called the epicycle, Greek for “upon the circle.” The planet moved like it was stuck to the tooth of a gear that was attached to the tooth of another gear with the Earth at its center. Ptolemy made mathematical refinements to the model that predicted the position of the planets with impressive accuracy for his time.

Simplified version of Ptolemaic concept of epicycles. The planet (red) appears to be in retrograde motion between positions 2 and 3. At positions 1 and 4, it appears to be moving faster than the stars. (Wikipedia)

Both the Ptolemaic and Copernican models shared a vital assumption that celestial bodies must move in perfect circles. This assumption reflected a common belief that the heavens embodied divine perfection and that the circle was the most “perfect” geometric shape.

Copernicus’ model was elegant, and it effortlessly explained retrograde motion—the earth’s circular path was merely overtaking the planet’s circular path, making the planet appear to move backward. But the model could not be made to predict the planets’ retrograde motion accurately. The Ptolemaic model, in contrast, was complicated, but it could be adapted to match the motion of the planets with impressive accuracy by freely layering epicycles on top of other epicycles until it worked. It is no wonder so many assumed the Ptolemaic model reflected reality.

The breakthrough came with Johannes Kepler in the early seventeenth-century, when he introduced the concept of planetary orbits that were shaped like ellipses rather than circles. Elliptical orbits, with the sun in the center of the universe and the earth arrayed with the other planets around it, allowed for a model that aligned with observational data without requiring complicated constructions of epicycles. The distinctive geometrical qualities of ellipses also left useful clues for why the planets were moving that way, opening the door to Newtonian physics and orbital mechanics. Ptolemy’s model was like an awkward adolescent fixation that held science back; Kepler’s paradigm was a building block scientists could usefully build upon.

Reasoning vs. Rationalization: A Key Distinction

Kuhn’s study of the Copernican Revolution highlighted the difference between two similarly sounding but very different mental tasks: that of reasoning and that of rationalization.

Both Copernicus and the advocates of Epicycles were trying to “adjust” the established paradigm laid down by Ptolemy so that it better aligned to observations, but their motivations were different. Epicycles only came into being in order to preserve an earth-centered ideal. This makes the model an example of rationalization, because it forces observed events to conform to a desired conclusion. Copernicus’ alternative, though a half step forward, shared the same basic flaw.

Kepler’s elliptical model, by contrast, emerged from a willingness to discard sacrosanct concepts (e.g., the perfection of circles, or Man’s central place in the universe) in an effort to align theory with evidence.

Reasoning seeks truth, even at the cost of comfort or tradition. Rationalization, by contrast and frequently without realizing it, seeks a way to preserve established ideas. Both figure prominently in political disputes, and it is not a coincidence that rationalization is invariably employed in politics to preserve ideas that are at the core of political life: the privileges of elites and the cultural identity of everyone else.

Nazi and Soviet Scientific Rationalization

One of the bizarre phenomena this distinction helps to explain is the almost comical errors of twentieth-century Nazi and Soviet science, two closed scientific communities that had been totally captured by a totalitarian state machinery.

At various critical junctures, these communities rejected the fundamental scientific discoveries of Mendel, Darwin, and Einstein in favor of ridiculous rationalizations that were ideologically correct and pleasing to their masters, but were disastrous in the real world. Crops failed in the Soviet Union – at the cost of millions of lives, at least in part because Mendelian genetics was sidelined. Quantum science was retarded for a generation in Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia because it was defamed as “Jewish science.”

I got a personal glimpse of this years ago when I interviewed an elderly geneticist whose early university studies took place in post-war Germany. It seems that in the interwar period, some Jewish scientists in Germany had correctly determined that human genes were carried in a package of 46 chromosomes (23 pairs) in each cell of a human’s body. In the thirties, as Nazi ideology prevailed and Jewish scientists had been ferreted out of German academia, the number 46 stuck out as “Jewish” and disrespectful: Why 46 chromosomes rather than the more noble-seeming number of 48?

The elderly scientist I was interviewing began his studies in the post-war university town of Jena in what was at the time East Germany. In the aftermath of the devastating war and under communist austerity, new textbooks were a distant memory, so he began his genetic studies using pre-war Nazi texts.

One of these textbooks confidently conveyed that the normal human cell contains 48 chromosomes. Except of course for Jews, who only have 46 chromosomes.

Our Own Era of Outrageous Rationalization

I’m beginning to think that the distinction between reasoning and rationalization may be the defining political question of our times. The Jewish chromosome anecdote illustrates how rationalization often becomes a weapon in political struggles over privilege and identity. Reasoned criticism—such as pointing out the lack of evidence that Jews have fewer chromosomes than anyone else—can be batted away as an impudent threat to unimpeachable beliefs or sacred narratives.

American politics today is characterized by the regular introduction of new rationalizations that seem to emerge out of nowhere, the ideological equivalent of epicycles that have no reason for being other than they are required for something else to be true. The Deep State became a thing that explained why, exactly, something I did not think was happening was actually happening. And we all have to deal with the tiresome narrative of the Stolen Election of 2020, belief in which is now generally understood to be a prerequisite for holding federal office in the Trump administration.

Each of these assertions has become the dominant paradigm of a community of like-minded people. It explains what we are seeing—rationalizes events—in a way that serves that community’s interests. It is not hard to figure out how the two previous examples of tiresome rationalization serve the interests and line the pockets of the MAGA-aligned elite.

And now, new to me at least because social media algorithms sensed I was a poor target for it, there is another set of rationalizations involving Jeffrey Epstein: how he was the liberal elites’ entrée into a vast child sex ring, how these elites managed to snuff him out in prison, and how Trump and his allies of right-wing media figures were decent people’s only avenue to blowing the lid off the whole sickening scandal.

But that idea, as the dominant political paradigm, is in trouble.

The Epstein Narrative Teeters

Unlike the other examples of rococo storytelling in the service of the far-right, those who have long thrived in their promotion of the Epstein narrative have obviously lost the plot and are looking around suspiciously at each other.

When it comes to Epstein, the reliable political mechanics don’t seem to work the way they have always worked: when the familiar hot-buttons are pushed, Hillary Clinton and George Soros don’t squeal, but Donald Trump and his stable of B-list sycophants do. Trump senses this, and has sent the word out to stop pushing those buttons, but the cottage industry employed in producing MAGA piece work relies on the story to put bread on the table.

Boiled down to its essence, the political problem is this: Now that MAGA diehards comprise the Deep State, the MAGA community’s dominant paradigm about Jeffrey Epstein and the dark workings of the Deep State don’t work anymore. MAGA rationalizations—the modern equivalent to epicycles that only exist to keep the dominant paradigm intact—fall flat: Trump tried stacking the “Democrat Hoax” block on top of the old way of looking at things, and that only made things worse with his most loyal supporters.

The situation has a straightforward Kuhnian explanation. The MAGA community can’t keep building on its dominant paradigm: It has to stop and throw out some assertions until the logical inconsistencies can be resolved before it can return to building again.

If you’re disdainful of MAGA world, enjoy your schadenfreude, but don’t get your hopes up. MAGA’s belief system is still intact enough, and its actors still see it as politically useful. The communal instinct is still to debug the dominant paradigm rather than discard it. But as Kuhn shows, there comes a point when rationalization can no longer hold a paradigm together—when the anomalies overwhelm the system’s internal coherence and can no longer be ignored, even by insiders.

If MAGA’s Epstein narrative continues to collapse under its own contradictions, if it can’t be made to implicate the “right” enemies – or worse, if it continues to implicate its own heroes – then we may begin to see an unraveling. The signs will be unmistakable. Formerly reliable propagandists falling silent or turning critical, grassroots confusion and apathy, and increasingly elaborate rationalizations that don’t even pretend to be coherent. At that point, the paradigm ceases to be a vehicle for power and becomes a liability.

Just like the Ptolemaic model eventually collapsed under its own contradictions, the Epstein narrative—once politically potent—is devolving into incoherence as we watch. The question on everyone’s mind is whether the other political narratives adjacent to it will start to collapse as well. Those who trade in toppling dominant paradigms should take heed.