Out with Christmas, In with Yule

A similar version of this article appeared in the Humanists of Minnesota newsletter and on their website blog in December 2011.

We call it Christmas, but for many of us the holiday is really about winter: enjoying it, surviving it, celebrating it. While others would remind us that the reason for the season is the birth of Jesus, “unbelievers” and Christians alike participate in a wide variety of midwinter festivities that mark this darkest time of year. But for the non-believer discomforts abound: ambivalence over cherished traditions, reservation in attending religious services to appease loved ones, wariness in how to be both tolerant and authentic, irritation at ubiquitous religious messaging, just to name a few. In an increasingly multi-ethnic, multi-religious and secular society, the celebration of Christmas as a de facto national holiday is problematic. But, then, it always has been.

Since its inception, Christmas has been as much a cultural holiday as a religious one. The early church leaders intentionally superimposed the feast of the Nativity on the Roman celebrations of Saturnalia and Kalends in late December to supplant allegiance to Roman deities and ensure the worship of Jesus instead. As Christianity spread across Northern Europe, regional harvest rites and Yule celebrations near the winter solstice also were recast with Christian symbolism.

For most of its history, however, the Christian Church had an uneasy alliance with Christmas given its dubious connection to Jesus’ actual birth and its association with the carnival-like festivities and pagan traditions that dominated the celebrations. By the time of the Reformation, purging the Catholic Church of its unseemly Christmas revels was an additional goal of some reformers with the Puritans going so far as to outlaw its observance altogether. Only in the past couple of centuries with the help of writers such as Washington Irving and Charles Dickens was Christmas transformed into a more genteel and domestic holiday.

Over time, obligatory feasts for subordinates, ritualized begging at homes of the elite, and community revelry deemed as a threat to public order all gave way to family oriented gatherings. Children became the new recipients of long-practiced holiday generosity. This reinvention of the season provided a more serene environment in which to commemorate Jesus’ birth. As a result, by the end of the 19th century, Christians were embracing Christmas with a newfound devotion that has continued to this day.

Nonetheless, non-religious festivities have endured and commercialization of the season has skyrocketed. It has become commonplace today, then, for ardent Christians to plead with us all to “keep Christ in Christmas.” Perhaps it’s time to establish a truce in this “cultural war” and reinvent the holiday season yet again but with 21st century sensibilities. Let Christians have Christmas to themselves and put an end to the duplicity of the holiday. The broader secular culture should uncouple the Christian “holy day” from the older, multifarious winter festivals to create a modern-day civic holiday in which everyone can participate and enjoy without its Christian overtones. Then the dilemma for non-believers of whether or not to celebrate becomes an unnecessary quandary, and Christians can exhort their own to celebrate Christmas with requisite piety as they wish. Leave the rest of us out of it.

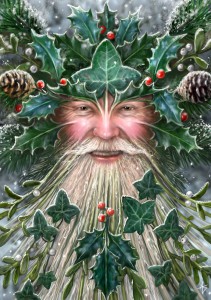

The battle over Christmas is better addressed by changing the focal point of the holiday itself. Secularists and humanists can help focus the season on the winter solstice—that pivotal shortest day and longest night in our journey around the sun recognized by both ancients and contemporaries. We can frame it as “Midwinter”—that medieval description of late November to early January as midpoint in the darkest time of year when ordinary life was suspended. We can call it “Yule” after that pre-Christian northern European celebration of harvest’s end, that festive respite from the hard labor of an agricultural economy and recognition of the turning year.

To retain “Christmas” as the nomenclature for this midwinter holiday is to needlessly divide us as a society and cast non-Christians as outliers in our culture. In renaming the season “Yule” to reflect its origins in the cycles of nature, we can celebrate our common humanity and acknowledge our shared joys and challenges of winter. And finally, distinguishing secular celebrations of the season from religious traditions establishes a much stronger basis for maintaining the separation of church and state without anyone having to play the role of Scrooge. For the season is not just about Christmas; in fact, it never was.

Let the Midwinter festival begin. Good Yule to everyone!