Religion, Violence, and Satire: A Humanist Response to the Charlie Hebdo Massacre

Update: According to the Epoch Times, one of the Charlie Hebdo attackers, Hamyd Mourad, has reportedly surrendered to French police, and two other suspects identified as brothers Cherif Kouachi and Said Kouachi, are on the run.

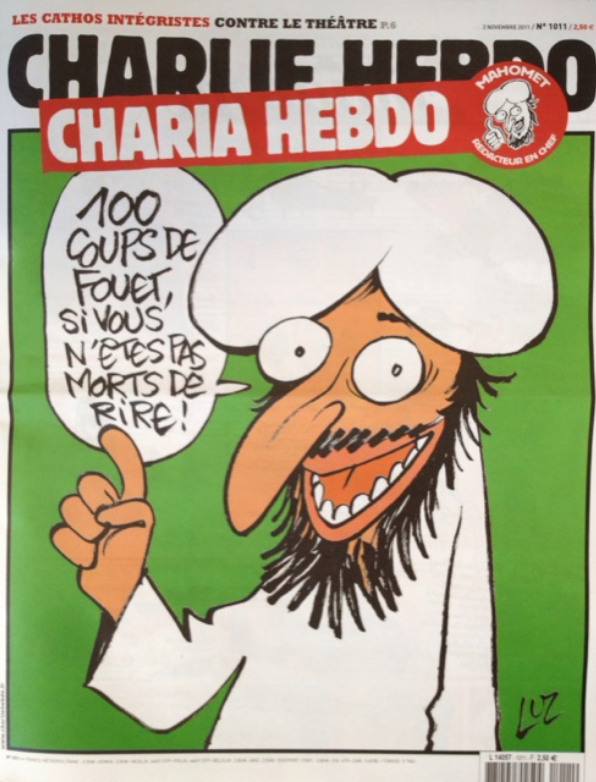

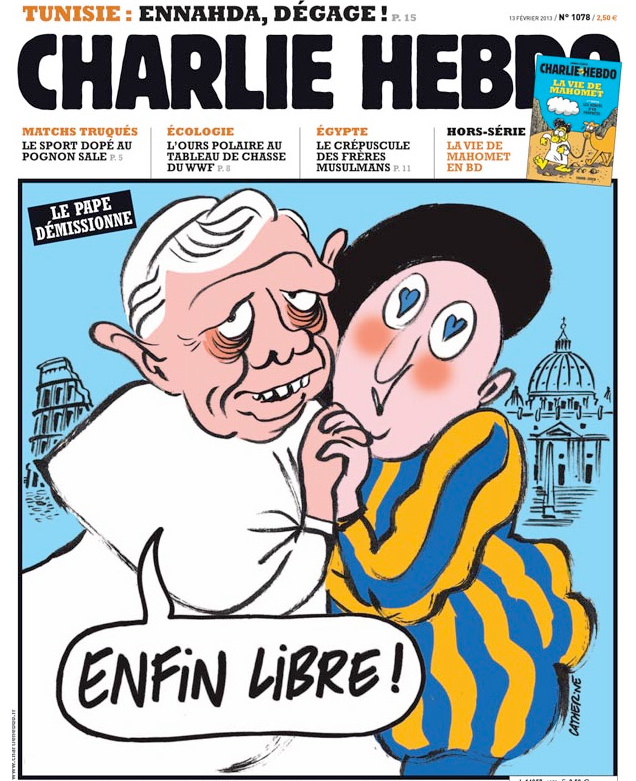

On January 7, 2015, twelve people were killed in a religiously motivated attack at the headquarters of the French satirical publication Charlie Hebdo. It’s being reported that the gunmen were Islamic extremists who yelled, “Allahu akbar!” (“God is great”) and said they were avenging their prophet Muhammad. (Charlie Hebdo has a long history of criticizing religions, has often depicted the Islamic prophet in cartoons, and has ridiculed both Islamic law and a leader of the Islamic State.)

When such acts of violence occur, it’s easy to say that Islam is the problem, that Islam is the sole source of violence for Muslim people, or that Islam is the most violent of the religions. Analyzing these events along the broadest spectrum is the frequent path of discourse, yet there are a constellation of issues at play that aren’t discussed enough (or are, frankly, avoided by those who should know better). In our common and casual narrative, the human element is often left on the cutting-room floor.

When such acts of violence occur, it’s easy to say that Islam is the problem, that Islam is the sole source of violence for Muslim people, or that Islam is the most violent of the religions. Analyzing these events along the broadest spectrum is the frequent path of discourse, yet there are a constellation of issues at play that aren’t discussed enough (or are, frankly, avoided by those who should know better). In our common and casual narrative, the human element is often left on the cutting-room floor.

When we talk about religion and violence, we need to remember the multiplicity of justifications, injunctions, and path-dependent influences involved, including socioeconomic factors, scripture, and culture. There are also actors. There are individuals and institutions. Individuals and institutions attack other individuals or other institutions through these influences.

With facts still emerging about the massacre at Charlie Hebdo, analysis of the myriad factors is conjecture. Economic instability in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) and Europe is likely at play, along with power vacuums in the Maghreb and post-colonial fallout between France and Algeria. We see the rise of far-right nationalism in France and the rise of Salafist terror directed at large-Muslim population secular states (especially those that focus international military efforts in the MENA power-vacuum states). We also must acknowledge that groups the world over see violence as an acceptable means to effect political change.

But those who publish satire carry the torch of free thought. That torch has yet to be snuffed out by the greatest of empires or the most zealous of actors. Another magazine editor said that satire was a human right. I disagree. Satire is more than a right, it’s an obligation. Satire is an obligation to continually connect ourselves to each other and break the bonds of what others say is impermissible for analysis. Satire gives power to the people of the day over those of the past and a ticket for participation for those yet to come. Satire is one of our more sophisticated and highly developed talents. For satire you need membership in a culture in order to appreciate the idiosyncratic repackaging of embedded meaning. To work, satire requires care—care of the satirist toward their target, and for the audience to care enough about that which is being examined anew. Satire is a robust precursor of personal and social growth. Certainly, to say that the violent attempt to suppress satire is a sign of growing pains is to minimize the tragedy that occurred in Paris yesterday.

But those who publish satire carry the torch of free thought. That torch has yet to be snuffed out by the greatest of empires or the most zealous of actors. Another magazine editor said that satire was a human right. I disagree. Satire is more than a right, it’s an obligation. Satire is an obligation to continually connect ourselves to each other and break the bonds of what others say is impermissible for analysis. Satire gives power to the people of the day over those of the past and a ticket for participation for those yet to come. Satire is one of our more sophisticated and highly developed talents. For satire you need membership in a culture in order to appreciate the idiosyncratic repackaging of embedded meaning. To work, satire requires care—care of the satirist toward their target, and for the audience to care enough about that which is being examined anew. Satire is a robust precursor of personal and social growth. Certainly, to say that the violent attempt to suppress satire is a sign of growing pains is to minimize the tragedy that occurred in Paris yesterday.

And yet we must remember the power of critique. When our news cycle is perpetuated by 140-character critiques of everything from plane crashes to the bare-fleshed backsides of the idle rich, we can forget our distance from the socio-political food chain that fosters violent attempts to suppress ridicule against sacrosanct authority, misogyny, classism, and racism. If we consider the amount of emotional disturbance required to murder someone for the sake of silencing dissent toward an idea, the power of critique unveils itself in perennial fashion.