Busting a Murderous Female Ghost (with Science & Humor)

Beginning October 13, 2017, news reports began appearing in India that some 100 men had fled the village of Kasiguda in the Adilabad District of the state of Telangana, leaving their homes and families behind for fear that a female ghost had been targeting males and killing them. Among the 400 village residents, those speaking with the media reported that seven people had died there in the last three years and that all of them had been young or middle-aged men. Some who had fled even claimed to have seen the ghost: “She was wearing white and we spotted her white hand! We are not coming back till that ghost is driven out of the village!” Taking refuge under a tree or at a relative’s home in another village was viewed as their only option.

I live in Telangana, and there, as in the neighboring states of Chathisgarh, Orissa, Karnataka, and Maharshtra, people routinely claim to be possessed by ghosts, exposing what should be recognized as a mental health issue. Instead, the ghost is commonly beaten out of victims by witch doctors and practitioners of black magic using neem leaves and branches. All of this brutality is meted out to the accompaniment of loud rhythmic music until the exhausted patient swoons with fatigue and the ghost is declared to have left.

A few years ago, in many districts of Telangana, parents stayed up entire nights keeping their babies awake, all because someone had heard voices declaring that any baby falling asleep would die. The warning had spread like wildfire. Afterwards, little action was taken by any officials. It was left to several humanists and skeptics like myself to use the medium of television to carry out a mass education program. Indeed, the state government looks upon superstition with a benign eye. Under semi-official blessings, a woman who claims to be possessed makes predictions every year for the entire state. Not surprisingly, her predictions are always in favor of the ruling party.

But it gets worse. Murders of men and women accused of performing black magic are regularly reported in the media. Our state ranks high in the number of reported murders. Some years ago 2,500 women were listed by the National Crime Records Bureau as having been killed over a ten-year period after having been accused of being witches. The men were not counted. Many murders go unreported and no one is looking into reports of child sacrifices. Telangana ranks high in all these sad statistics.

The story from Kasiguda about the murderous female ghost came at the back of reports from Khammam, another district: ghosts were not allowing people to enter the village even in daytime. People in another village in Khammam left their homes in a hurry because a priest ordered them to do so to ward off the evil spirits that were bringing them bad luck. It became clear that an epidemic was starting and we humanists and skeptics needed to do something before the hysteria spread even further.

So after learning of the Kasiguda haunting, it was with a sense of urgency that on October 19 I sent out an appeal on Facebook, calling for volunteers to join me in a visit to the village. They would need to participate in programs to popularize science and stay overnight in the village, doing so as a direct challenge to the now widespread belief that the ghost would kill any male sleeping there at night.

I added two more conditions. Since the female ghost was allegedly attacking only men, all the volunteers would have to be male. This led to some unrest among the women in my 22,000-member group, but I assured them that we would try to find for them a village infested by the rare male ghost! The last condition was even more important: the volunteers had to promise that they would not die the night we were spending in the village because that would prove inconvenient for the campaign.

Fifty people instantly responded and twenty-five joined in a convoy that went to the village. We had already sent Ajay B. Kumar in advance. He had been trained by us. So in his visit on October 18 he spent half a day with the villagers, observing, interviewing, and negotiating so as to understand the ground realities there. He learned it was a very poor Muslim village with no hygiene and sanitation, no street lights, and one where the last two deaths had been from jaundice and typhoid.

Importantly, we also informed the police and sought protection. Ventures such as ours can be extremely dangerous. There have been brutal attacks and murders by those aiming to benefit from the scare. And there have even been instances in the state when armed police were attacked by villagers in an effort to cover up the role of the entire village in a witch murder.

However, despite the seriousness of the matter, we didn’t see it as valuable or necessary to attempt social change with a forlorn face. What we wanted was a conversation around the subject. So it seemed that by making it interesting we might better spread the word, causing other villages to take an interest in our findings as well. We were, after all, not the government. We were doing this with personal resources, pooling cars and food. A repeat would be difficult in the short term.

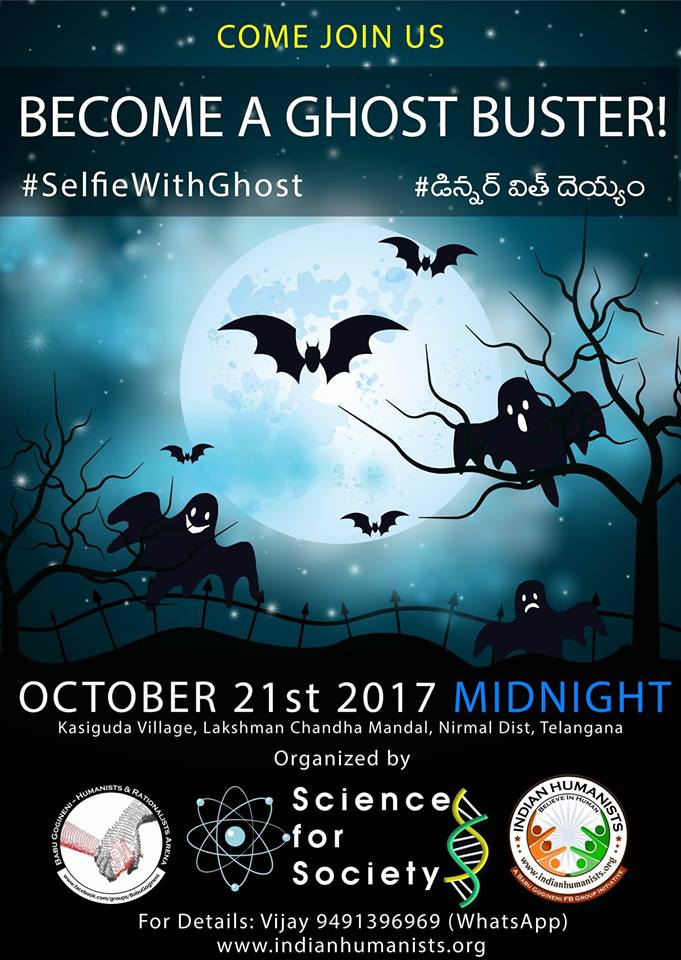

In this spirit we considered that if there were a female ghost in the village and people had seen her, then we would see her too, and so we marketed the event as an opportunity to take a selfie with the ghost.

In this spirit we considered that if there were a female ghost in the village and people had seen her, then we would see her too, and so we marketed the event as an opportunity to take a selfie with the ghost.

So, after designing some banners and posters, and after informing the media, off we went on Saturday morning, October 21. The INews TV channel came with us, complete with equipment and a crew of four to do a live broadcast. We all arrived at 3:00 PM.

But once there we were told by the village heads that they wouldn’t talk to us. What most villagers wanted was animal sacrifice as recommended by a neighboring village’s Hindu priest. Imagine that. A Muslim village following Hindu advice! And the local mayor, under whose jurisdiction a number of villages fall, had already backed the recommendation. They were collecting the 70,000 rupees needed for this, partially in the form of hundreds of eggs, some chickens, and some goats. With this payment, the priest would draw a magic line around the village to prevent a ghost from entering.

It took us a couple of hours to cajole the village mullahs into supporting us and advising the villagers accordingly. But they finally paid us heed, confirming that the last two deaths were because of typhoid and jaundice. We explained that this was because the water is unclean. The previous death was due to a motorbike accident. We regarded this as a matter of negligence. Further, it was a male who died in the accident because the women of the village don’t ride bikes.

They started thinking.

Then we were allowed to organize what we had come prepared for: an evening presentation by Mr. Chandraiah, a science popularizer, who performed science tricks and feats that appeared miraculous: producing fire from sand, pouring water on paper which actually sets the paper on fire, and so forth.

This excited the children, who went and brought their fathers—the few who had returned to the village—to see what we would do. A few women came in too, curious and hesitant, wearing the veil. The men sat in chairs, almost all the women on the carpet. Slowly the mood changed and they started laughing and responding to the magician’s science tricks.

Finally, we invited them to walk on burning embers. Some of the villagers simply loved this demonstration and wanted to participate again and again. When you walk fast and briefly on burning embers your skin isn’t burnt or scorched. In science this is known as the Leidenfrost effect. Any non-diabetic without injuries can try this under supervision.

Then we asked those who proved they could walk on fire if they were still afraid of a ghost they couldn’t even see.

Then we asked those who proved they could walk on fire if they were still afraid of a ghost they couldn’t even see.

As a next step we walked around with the villagers in the areas where they said they’d seen the ghost. We set up video cameras in their dark streets and showed that nothing suspicious was captured. And in a finale we went to the cemetery shortly before midnight and stayed a couple of hours. And because their fear was that no male could sleep in the village overnight, we announced that we twenty-five males would sleep in the village until morning. Then they could count how many of us were still alive.

Four members of our group, who traveled over 500 kilometers for this, were over seventy years old. Two of them couldn’t walk easily even with a stick. Yet they came, in a country where life expectancy is in the mid-sixties. The youngest was my son, who is thirteen. We all stayed awake and did a Facebook Live from the cemetery. There were 40,000 people who watched.

No ghost appeared. But there were many frogs and many scorpions, the latter of which had to be killed, and we avoided the snakes.

And then we went to bed, some sleeping in the open on the ground and some in cars. After sunrise there were still twenty-five of us.

Babu Gogineni takes a selfie in front of the “I am a Ghost Buster!” poster

We organized a morning meeting and invited the villagers to give their opinions and impressions. They came one after the other to say they were convinced there was no ghost and that they would persuade their friends to come back. In fact, a few of the fleeing men had returned. The children and the adults came forward to take selfies in front of our poster that read: “I am a Ghost Buster!” We discussed concepts of the soul and the afterlife and the impossibility of ghosts. Even some of the journalists who were there to cover the story became convinced. We had also arranged for a psychiatrist, Dr. Rajender, to counsel the villagers.

Afterwards, in a most heartwarming response, two of the people who had believed in ghosts offered to join us as volunteers to go to the next village where there might be a ghost scare and help educate others. The campaign also caught the imagination of many youngsters who now want to do the same in their own villages where there are ghost scares. We made sure everyone understood both the gravity and the complexity of the problem. It is not a problem that can be addressed by denouncing gods or ghosts; it needs patient explanation, opening a conversation, making sure we are not thinking for the victims, bringing in insights from both sociology and psychology, and, finally, getting the administration to act—which they didn’t do until then. We had started a movement for reason through a humanist intervention in a social crisis.

And, of course, involving the media so that our message would have a multiplier effect was significant. There were fifteen television reports and special discussions on the subject, a live coverage lasting over four hours, good reports in the print media, and reports by BBC and two national news organizations. And all it cost us was the travel expense to Kasiguda. We didn’t even have to pay for a hotel; the cemetery doesn’t charge for overnight stays!

All photos courtesy Babu Gogineni.