Secular Suffragists

Religion has long played a powerful role in the subjugation of women. As humanists who champion human agency, including the freedom of and from religion, we have chosen to highlight several suffragists who vocally challenged the white Christian patriarchy and its theocratic justifications for suppressing women’s rights, including the right to vote. While these women were in the minority in terms of their agnosticism or nonbelief, it follows that their white privilege and economic security afforded them more freedom to identify as secular than their Black counterparts.

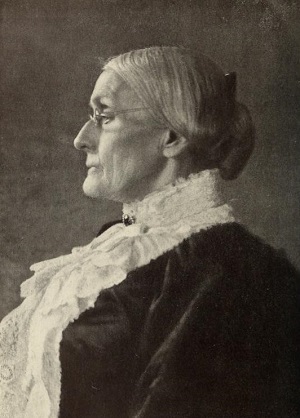

Susan B. Anthony

SUSAN B. ANTHONY was born into a family of activists, including her father who was a strong supporter of the movement to abolish slavery and who instilled in his daughter a commitment to fight for social change that guided her life. Anthony was a teacher until the age of thirty, when she fully dedicated herself to social reform through the areas of temperance, antislavery, and later suffrage.

Following the passage of the Fourteenth Amendment to the US Constitution, Anthony attempted to vote in the 1872 presidential election. Though she was arrested, the resulting trial was widely publicized in the press and helped launch women’s suffrage onto a national platform. Riding the newfound wave of national support, Anthony traveled the country to deliver speeches on the need to secure voting rights for women.

Anthony’s experiences with religious life demonstrate her rejection of oppressive theology, though not an outright rejection of religion itself. She was raised in the liberal Quaker faith, and when the Quakers split in the early 1800s her family joined the Unitarian-leaning “Hicksite” sect of the religion. She later joined the Congregational Friends organization in western New York, which in time ceased religious activities and became known as the “Friends of Human Progress,” an early interfaith group that championed social progress. Though ultimately unsuccessful, Anthony attempted to start a “free church” in 1859 that sought to eschew oppressive doctrine and be welcome to all.

She was heavily influenced by Theodore Parker, a Boston-based Unitarian minister who rejected biblical authority and questioned the nature of religious miracles. Anthony was also close with William Gannett, a Unitarian minister in Rochester, New York, who was instrumental in opening the religion up to non-Christians and even nontheists by rejecting the authority of any formal dogma.

Recounting a memory of comforting her sister Hannah as she approached death, Anthony wrote that she “could not dash her faith with my doubts, nor could I pretend a faith I had not.”

Though deeply involved with the more liberal-leaning sects of religion that more naturally housed progressive activism, it was Anthony’s view that suffrage would succeed only through united support of both the religious and nonreligious. “I have worked forty years to make the [suffrage] platform broad enough for atheists and agnostics to stand upon,” she wrote, continuing, “and now if need be I will fight the next forty to keep it Catholic enough to permit the straightest Orthodox religionist to speak or pray and count her beads upon.”

When viewed through a contemporary lens, Anthony’s legacy on race, as with most activists of her time, is complicated. As noted by Linda Lopatra, director of visitor services at the National Susan B. Anthony Museum,

Anthony was almost universally reviled for her antiracist views. White historians, to prove their antiracist bonafides, have often ignored this fact, by taking her quotes out of context. Other white historians have focused entirely on Susan B. Anthony’s anti-slavery work and close relationships with black women, but ignored her willingness to work with racist suffragists. It is as if she is a proxy for our own struggle with racism.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton

ELIZABETH CADY STANTON rejected all religion, was an ardent abolitionist, and supported the temperance movement.

In her autobiography, Eighty Years and More, Stanton wrote about the nontheistic awakening she had while studying at the Troy Female Seminary in Troy, New York: “My religious superstitions gave place to rational ideas based on scientific facts, and in proportion, as I looked at everything from a new standpoint, I grew more and more happy, day by day.”

And she was clear that her criticisms weren’t just of the Christianity with which she was raised. Speaking generally of women, Stanton declared that “All religions on the face of the earth degrade her, and so long as woman accepts the position that they assign her, her emancipation is impossible.” Stanton was the author, along with a committee of other women, of The Woman’s Bible, an analysis that challenged, among other issues, the traditional biblical view that women should be subservient to men.

Stanton was also the principle author of the Declaration of Rights and Sentiments, which resulted from the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention she organized with Lucretia Mott and others. Modeled on the Declaration of Independence, the statement set out the argument for attaining full rights for women, including a then-controversial call for the right to vote. Frederick Douglass attended the meetings and was a strong supporter. Stanton viewed the convention as the first step in women attaining equality with men.

Twenty years later at a convention in Washington, DC, she gave a powerful speech calling for the vote for women. “With violence and disturbance in the natural world, we see a constant effort to maintain an equilibrium of forces,” she said, concluding, “If the civilization of the age calls for an extension of the suffrage, surely a government of the most virtuous educated men and women would better represent the whole and protect the interests of all than could the representation of either sex alone.”

But Stanton is a problematic heroine since she did not extend her belief in the rights of women to all people. Although she had been a staunch abolitionist, once slavery was abolished by the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment, she vehemently argued against the passage of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments because they didn’t protect women.

Largely due to Stanton’s unorthodox religious views, her friend Susan B. Anthony was the more famous of the two. But Stanton is included, alongside Anthony and fellow activist Sojourner Truth, in a new memorial commemorating the women’s rights movement that will be unveiled in New York City’s Central Park this year.

Matilda Joslyn Gage

MATILDA JOSLYN GAGE was an abolitionist, an advocate for Indigenous people’s rights, and a freethinker who vehemently opposed the entanglement of religion and government. Her parents were abolitionists and liberal intellectuals, and the family home was a safe house along the Underground Railroad.

She attended the Clinton Liberal Institute in Clinton, New York, and at the age of eighteen wed Henry H. Gage, a merchant, to whom she was married until his death in 1884. They made their home in Fayetteville, New York, and had five children together. As a young wife and mother, Gage wrote newspaper articles and continued to offer refuge to people escaping slavery. In 1850, a month after the Fugitive Slave Law passed, she issued a statement refusing to obey it, in essence daring authorities to fine and jail her.

In 1852 Gage spoke at the National Women’s Rights Convention in Syracuse, New York. She helped found the National Women’s Suffrage Association in 1869 and served as president from 1875 to 1876. She worked alongside Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton for many years, collaborating with them and Ida Husted Harper in writing the multi-volume History of Woman Suffrage and editing NWSA’s official newspaper, The National Citizen and Ballot Box. However, Anthony saw Gage as too radical for her fierce advocacy for church-state separation, criticism of Christianity, and also for her belief in racial equality.

When the NWSA merged with the more conservative American Woman Suffrage Association in 1890 to form the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), it became clear to Gage that she did not belong there. She formed the Woman’s National Liberal Union, the goal of which was, in part, to “arouse public opinion to the danger of a union of church and state through an amendment to the Constitution, and to denounce the doctrine of woman’s inferiority.” Gage was also the editor of the union’s journal, The Liberal Thinker.

In 1893 Gage published the book, Woman, Church & State: The Original Expose of Male against the Female Sex. It was inscribed “to the memory of my mother, who was at once mother, sister, friend,” dedicated “to all Christian women and men, of whatever creed or name who, bound by church or state, have not dared to think for themselves,” and addressed “to all persons, who, breaking away from custom and the usage of ages, dare seek truth for the sake of truth. To all such it will be welcome; to all others aggressive and educational.”

That same year Gage, who had written for years in castigating terms about the US government’s gross mistreatment of Native people and had spent time with the Iroquois, was admitted into the Iroquois Council of Matrons.

Gage died in Chicago in 1898 of a stroke at the home of The Wizard of Oz author L. Frank Baum, who was married to Gage’s youngest daughter Maude. She was cremated, and a memorial stone was set at Fayetteville Cemetery bearing the words: “There is a word sweeter than Mother, Home or Heaven. That word is Liberty.”

As we commemorate the suffrage centennial, we must reflect on how marginalized voices were left out of conversations about equality for all in the United States. The passage of the Nineteenth Amendment was not a completed goal—it was a milestone in a long effort. In subsequent years Jim Crow laws and other legislation inhibited Black, Native, and Asian people from voting. Those laws are gone, but marginalization is not. The corrupt criminal justice system still silences voices today and voter discrimination still thrives in the United States. As we celebrate 100 years of women voting in the United States, we also acknowledge the current fight for Black lives and many injustices that people of color face because of the racism embedded in our systems.

Jennifer Bardi, Peter Bjork, Nicole Carr, and Caroline Peters contributed to this article.