The Call of Disobedience: Lessons for Social Change from Our Feminist Foremothers

Suffragists hold banners in front of the White House in 1917.

Suffragists hold banners in front of the White House in 1917. In 1878 Congress first considered a constitutional amendment that read:

The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

The proposal, doggedly championed by female suffragists, was reintroduced annually but failed to pass for forty-one years. Congress finally passed the Nineteenth Amendment acknowledging women’s legal right to vote on June 4, 1919. The next year, on August 18, 1920, the amendment was ratified.

We are indebted to our feminist foremothers for advancing women’s rights and for combating the oppression of women in our society. As we commemorate the Nineteenth Amendment centennial, we should do more than praise their achievements. We should strive to emulate the best of their imperfect example, learning from their insights into patriarchal culture and the nature of social change itself. (Note: space limitations and the knowledge that other contributions to TheHumanist.com’s centennial coverage address the failure of white suffragists to overcome ethnocentric and classist biases preclude my doing so here).

In 1848, seventy-one years before the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and female Quakers hosted the Seneca Falls Convention in New York, the first large public meeting advocating for women’s rights. Abolitionist Lucretia Mott was inspired to organize the convention after being prevented from fully participating in the 1840 Anti-Slavery Convention in London because she was a woman.

Three years later Stanton met Susan B. Anthony. The two went on to become lifelong friends and allies in the fight for women’s equality. In 1872 Anthony and thirteen other women succeeded in voting, against the law, in Rochester, New York. Anthony was later arrested and put on trial. As Susan Shaw and Janet Lee write:

She appeared before every Congress from 1869 to 1906 to ask for passage of a suffrage amendment. Even in her senior years, Anthony remained active in the cause of suffrage, presiding over the National American Women Suffrage Association…from 1892 to 1900.

Anthony labored for women’s rights for five decades but died fourteen years before women won the right to vote in the United States. What lesson does this offer us? First, her life and work stand as powerful rebukes to the contention that social change activism is the work of the young. Anthony fought for women’s rights into her eighties.

Of course, Anthony wasn’t alone in laboring for a posthumous victory. Many champions of women’s rights died long before the gains in voting rights, access to contraception, property rights, and educational opportunities were achieved.

One was abolitionist and itinerant preacher Sojourner Truth. Three years after the Seneca Falls Convention, she delivered a speech at the Women’s Rights Convention in Akron, Ohio. Truth drew on her own experience to explode male-conceived myths of “femininity.” In the earliest transcription of her speech we read:

I have as much muscle as any man, and can do as much work as any man. I have plowed and reaped and husked and chopped and mowed, and can any man do more than that? I have heard much about the sexes being equal; I can carry as much as any man, and can eat as much too, if I can get it. I am as strong as any man that is now.

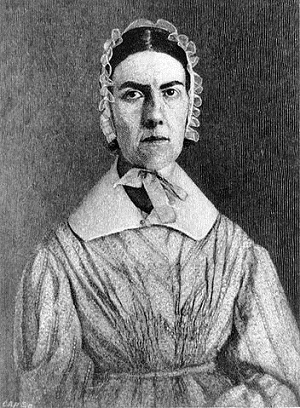

Frances Ellen Watkins Harper

Born to free black parents in 1825, Frances Ellen Watkins Harper was another feminist foremother who lent her intellectual capabilities to the causes of abolition and suffrage. In 1858, Harper, a poet, writer, and active Unitarian, refused to give up her seat or ride in the “colored” section of a segregated trolley car in Philadelphia. And during the 1866 National Women’s Rights Convention and the 1869 meeting of the American Equal Rights Association she challenged her white female counterparts to recognize and consider the unique experiences and plight of black women who faced not only a denial of rights from the male world but who were also discriminated against by white women. “You white women speak here of rights,” she said in her 1866 speech. “I speak of wrongs.”

Harper died in 1911 and Truth in 1883. Neither tasted the fruits of their labor for suffrage. That many working for women’s social equality never tasted these fruits reminds us that the successes of one age are born out of the long, tiresome toil of preceding ages.

Our feminist foremothers teach us that repeated failure isn’t certain evidence that one cannot succeed. The tireless struggles of Stanton, Anthony, Truth, Harper, and others to achieve the right to vote for women teach us that progress and justice are dead without faithful and imaginative conviction in one’s cause.

Our feminist foremothers’ efforts also teach us that the most laudable of social changes, including the end of child labor, abolition of slavery, ending segregation, protecting children from abuse, combating homophobia and achieving marriage equality, and the struggle for women’s rights, were born of immoderate advocacy and sacrifice.

In 1836, when the Grimké sisters—Sarah and Angelina—spoke out against slavery as members of the Quaker organization called the Society of Friends, they were condemned. At the time, the Council of Congregational Ministers of Massachusetts issued a statement:

The power of a woman is her dependency flowing from the consciousness of that weakness which God has given her of her protection…when she assumes the place and tone of man as a public reformer, she yields the power which God has given her for her protection and her character becomes unnatural.

Wood engraving of Angelina Emily Grimké

As Angelina addressed a racially integrated abolitionist group at Pennsylvania Hall in Philadelphia on May 17, 1838, thousands gathered in protest. The mob threw stones and broke windows during Angelina’s speech—rather than fleeing the threat, she integrated commentary on the mob in her speech and continued to the end. Later in the night the mob burned the hall to the ground. Just speaking in public, as a woman, during the early 1800s was revolutionary.

Consider the bold words of Angelina Grimke in 1835 after a pro-slavery riot in Boston, urging abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison to continue with the cause despite the danger of doing so. “If persecution is the means which God has ordained for the accomplishment of this great end, Emancipation; then…I feel as if I could say, let it come; for it is my deep, solemn, deliberate conviction, that this is a cause worth dying for.”

We commit the argument to moderation fallacy, also called the false compromise, when we mistakenly believe that something is necessarily true or good just because it is “moderate” or in the “middle” of two conflicting views. Consider what the moderate position would have been between the Grimké sisters’ claim to the right to publicly advocate for their beliefs and the Council of Congregational Ministers of Massachusetts contention that it is unnatural for women to do so. Should our foremothers have found a half-way point between women’s equal share to political freedom and their being restricted to the home where women were expected to submit to men? We all know the answer does not stand between these two positions. One is right and the other is wrong. The fact that the wrong position is also long-standing and culturally commonplace does not, therefore, give it standing in shaping our determination of what’s right.

When our feminist foremothers claimed women were independently entitled to basic rights, they were challenging a 5,000-year-old system of belief and practice that presumed the superiority of males over females. To win the freedom women today rightly enjoy, they had to imaginatively and perspicuously see through the dehumanizing fog of cultural norms to recognize women’s full humanity. Our cultural and our moral lens are clearer as a result.

Our feminist foremothers offer us a lesson that must be learned again and again: those in power are typically the defenders of the status quo, and when an oppressive ideology is culturally normalized, naturalized, or portrayed as divinely ordained, it becomes one of the most important mechanisms of oppression. The normalization of women’s subordination is the context that allows us to appreciate Anthony’s bold refusal to partner with patriarchy:

The old idea that man was made for himself, and woman for him, that he is the oak, she the vine, he the head, she the heart, he the great conservator of wisdom…she of love—will be reverently laid aside with other long since exploded philosophies of the ignorant past.

As Harper concluded in an 1875 address marking the centennial of the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery, “Apparent failure may hold in its rough shell the germs of a success that will blossom in time, and bear fruit throughout eternity.”

Today we remember the incendiary and disobedient spirit of the women who dedicated themselves to the cause of agency, and whose labor yielded fruits we must still protect today.