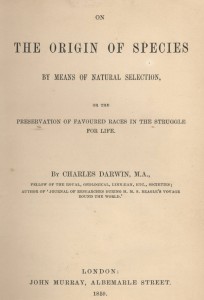

The Reception of Darwin’s On the Origin of Species Historical British Periodical Perspectives (Part Two)

In the previous article, we asked the question if Darwin’s theory actually produced a crisis of faith within evangelical communities in England when they were first published. Scholars have asserted that after the publication of Darwin’s theories, people in nineteenth–century England found it harder to maintain faith in what they had once held to be dear. Perhaps they had been challenged even further to dissociate themselves from something that they had never truly believed in the first place?

Some authors took issue with Darwin on this point. The author of an 1862 unsigned article published in The Baptist Magazine defended the divine sovereignty as creator and sustainer but also painted a bleak picture for the order and upkeep of the universe if there is truth to Darwin’s theory. The author stated that though it is difficult to discover whether or not Darwin has denied the existence of a deity, there seems to be no room for God in “the cycling of the world . . . nature is thus regarded as automatic, or self-acting.” Therefore, the challenge to a divine design as well as Providence functioning as a superintendent in the world was troublesome to this author. If Darwin’s theory of natural selection was correct in that nature was not harmonious but engaged in constant competitive struggle for survival, it could be theologically inferred that God’s creation was a consequence of that destruction, making God the supreme divine destroyer. In place of the uniting spirit of harmony within creation, it is implied that Darwin’s theory sees the individual as regarding itself as the center of existence, sending both humanity and nature to a life of struggle with itself for primal existence.

The British Quarterly Review conducted a review of the significance of The Origin of Species in 1860. After offering general praise to Darwin’s work of more than twenty years, the reviewer readily admits that nature is constantly laboring to “improve her productions.” Without mentioning a god in the article or alluding to theological implications connected to struggle, the reviewer challenged Darwin by stating there is “an unnatural propensity on the part of all improved breeds to exterminate the stock from which they have sprung.” The end result of such a struggle would eventually lead to the extermination of the “parent line,” which would ultimately be ruined by the younger race. (On the other hand, Bishop Samuel Wilberforce recognized the struggle for existence, but still maintained that the work of “Providence was provision against the determination, in a world apt to deteriorate.”)

For Christians, in particular, the questions directed against the validity of the Scriptures were not isolated to the Hebrew Scriptures’ accounts of creation, flood, and other myth narratives. Since practically all Christian traditions in the United Kingdom at the time held that both testaments were inspired, then repercussions were whispered to the Christian New Testament as well. If creation was no longer viewed as a miraculous work of God, but rather was ascribed a scientific explanation, then what was to stop anyone from lodging an enquiry into other miracle narratives, such as the incarnation or the resurrection? The entire foundation of the Christian message of the birth, life, death, and resurrection of Jesus was now being called into question.

There is but one reaction that would be expected from such implications: an outright rejection of the theory that is attacking what is held to be the dearest to the Christian belief. An unsigned article was submitted to The Evangelical Magazine in 1861, and its demeanor and tone reflected the author’s disgust that anyone would even dare to suggest the implausibility of miracles. The author was keen to defend that if but one “divine mystery” is merely a story, then this will have an effect on the Christian New Testament’s validity, including the narrative elements (death, resurrection, etc.) upon which the Christian faith is grounded. The author called upon the reader to make a move of faith, or a re-confirmation of their faith, stating that if a person can believe in the virgin birth of Jesus, then what stops them from professing belief in other miracles?

Though Darwin did not specifically reject the idea of a supreme creator, he posited a system of natural laws that utilized chance variations instead of following a definite, predetermined order. These laws came uncomfortably close to suggesting the lack of a need for an independent creator, and the non-conformist community reacted to such suggestions. Most contributors to non-conformist periodicals were quick to come to the defense of the belief in a deity as the sole creator of all that exists. Other authors like Charles Haddon Spurgeon denied in his 1862 article in The Metropolitan Tabernacle Pulpit that Darwin is suggesting that God could not be the creator but rather is posing a series of queries to the methods of creation that God has utilized. Other anonymous authors attempted to hide the issue in the obscurity of pre-history, accepting creation to have transpired in the remote past, but that this hypothesis is all that they seem willing to accept.