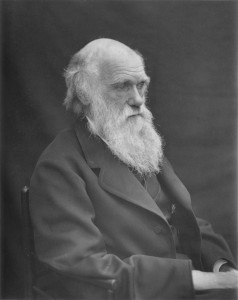

The Reception of Darwin’s On the Origin of Species Historical British Periodical Perspectives (Part Three)

We have been asking in this series if Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection actually produced a crisis of faith within evangelical communities in England when first published. All articles submitted to the British periodicals examined in Alvar Ellegård’s 1990 book, Darwin and the General Reader, took offense at the thought that the “crowning achievement” of God’s creation could foster any such connection to animals. Some contributors insisted that it was the intellectual superiority and the spiritual nature of humanity, or the human possession of morals that differentiated human beings from the animal orders. Others saw the identification of humanity with the animals as a personal affront: “certainly derogatory to the greatness of man, and presents us with a painful caricature of our history.”

It is at this point that the issue of race is worthy of mention. During this period, race and the issue of African-American slavery was a topic of concern in theological, political, and anthropological circles in the United States. Darwin’s theory could be used for either side of the debate, both pro- or anti-slavery, alike. However, Darwin’s theory seemed to fall in line with an anti-slavery audience: to deny the separation of the varieties of species meant that there was no room to suggest “superiority” or “inferiority” amongst the races of humanity. “Slavery was therefore not an inviolable condition of nature but an ephemeral condition of history; by nature, all men were brothers [sic].” This sentiment can be detected in an article proclaiming that an evolutionary theory is difficult to explain if, for no other reason, humanity’s mistreatment of its own. One author wrote in The Christian Witness that African slavery was not the result of “rapacity and fraud,” but arose from ‘“a rude instinct adapted to the then conditions of society.”

If humanity can no longer believe in the harmony of creation, profess a belief in God’s Providence, or trust in biblical truths, is there any room at all for any religious or ethical beliefs? The answer was a resounding “no.” Darwin had expressed that religious beliefs were actually an evolution, too, though they had participated in the evolutionary process of humans by the reinforcement of ethical codes by remorse. However, the moral sense (conscience) was a product of utility in the earliest epochs of human society, and it had been forged from a social instinct, devoid of religion or God, expressing itself in the drive for approval of one’s actions from their peers.

Given the dates of these reviews and articles, the debates of Darwin’s theories were not of prime importance to the British evangelical communities, or at least not of prime importance to the editorial staff of the periodicals. It was frequently the case that articles on mission efforts, reports from churches across England, debates on political issues, education, and pastoral admonitions/encouragement received the most attention. It seems the heated debate regarding Darwin’s theories would be reserved for American audiences, many years into the future.

Read all articles in this series

Appendix of Contributors to Periodical Articles

Allon, Henry (1818-1892): Congregational minister, succeeding Thomas Lewis at Union Chapel, Islington. Among other things, Allon is noted for being called twice to the chair of the Congregational Union, and a regular contributor for the British Quarterly Review, editing the journal for twenty years from 1866.

Cameron, Robert (1814-1887): Trained at Horton College, Bradford, and pastored a church at Branch Road, Blackburn, which eventually divided over the issue of communion in 1847, but reunited in 1864 at which time Cameron was reinstated as the pastor. In 1878, Cameron was appointed secretary of the Leeds Nonconformist Ministers’ Association: a position he fulfilled until his death. Between the years 1877 and 1887, Cameron was a regular contributor to the Baptist Magazine.

Cobbe, Francis Power (1822-1904): philanthropist and religious writer, Cobbe was born into a family that included five archbishops (Charles Cobbe, archbishop of Dublin was her great-great-grandfather) and one bishop. Though she had a conversion experience when she was seventeen and was confirmed by Archbishop Richard Whately at Malahide, she eventually drifted into agnosticism, but recovered her faith within Unitarian circles. Cobbe is noted for her work against vivisection as well as her encouragement of women’s rights and suffrage alongside Mary Carpenter who encouraged her to take interest in the progressive movements in India.

Stock, John (1817-1884): Baptist minister of a variety of churches (Chatham, Salendine Nook, Huddersfield [twice], Devonport). Stock was also active in the workings of the Psalms and Hymns Trust, served as an examiner at Rawdon College, and was president of the Yorkshire Baptist Association. He is also noted for his work with such causes as peace and the abolition of slavery.

Titcomb, Jonathan Holt (1819-1887): Non-Baptist. Author of, Baptism, Its Institution, Its Privileges and Its Responsibilities, and The Washing of Regeneration: A Sermon in Reply to the Rev. C. H. Spurgeon. Graduate of St. Peter’s College, the University of Cambridge. Whilst a curate of St. Andrew-the-Less in Cambridge, Titcomb was a popular preacher, and had instituted a Sunday school and district visitors in his parish before acting as secretary to the Christian Vernacular Education Society of India. After a notable career in London, he was appointed the first bishop of Rangoon in British Burma, and began his ministry there on February 21, 1878. After a fall over a cliff in the Karen hills in 1881, Titcomb returned to England, where he resigned his bishopric, but was ultimately appointed by the bishop of London to be his coadjutor to the supervision of English chaplains in Northern and Central Europe (1884-1886).