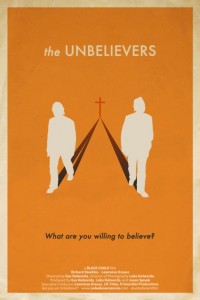

Science, God, and Rock ’n Roll (Part 2) An Interview with "The Unbelievers" Co-Star Lawrence Krauss

The American Humanist Association will be screening The Unbelievers at our Annual Conference on Thursday, May 7! Read our March 31, 2014 interview with co-star (and 2015 Humanist of the Year) Lawrence Krauss below. Click here to read part one of this interview with Unbelievers director Gus Holwerda.

A physicist, a zoologist, an imam, and a priest walk into a debate about origins…

It’s no joke. Rather, it’s a glimpse into a documentary on the quest of two scientists to confront religion head-on. Zoologist and evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins and physicist Lawrence Krauss, each a bestselling author, have been traveling the world together to champion the virtues of science and reason and shatter the pretensions of religion.

The new film, titled The Unbelievers, follows the pair—backstage, onstage, and aboard limos and trains as they journey from Australia to London to Washington, DC, and points in between. If you think this sounds like a rockumentary, you’re not far off the mark.

The Unbelievers was made by brothers Gus and Luke Holwerda, who sprang from a rock-n-roll background to become filmmakers. (Their band Smokescreen describes itself as an “alternative / experimental / indie / sci-fi / rock band with a long list of influences.”) Their documentary premiered last year and had brief theater runs in New York and Los Angeles. Now, a release on DVD and other media looms. Here, our Science and Religion Correspondent Clay Farris Naff interviews one of the film’s stars, Lawrence Krauss.

Click here to read Naff’s interview with Unbelievers director Gus Holwerda.

(The interview took place by email and has been lightly edited for stylistic consistency.)

TheHumanist.com: When were you first enchanted with science, and who were the figures in your life that inspired you to a career in physics?

Lawrence Krauss: I read books by scientists and about scientists from an early age. (My mother wanted me to be a doctor). Reading about Galileo when I was ten or eleven had a big impact. Then, reading books by Albert Einstein, Richard Feynman, James Jeans, and Isaac Asimov really did it. One of the reasons I write now is to return the favor to young people today.

TheHumanist.com: Like many others, I first heard of you when as a department chair at Case Western Reserve in Ohio, you took a stand against so-called intelligent design (ID). Is it fair to say that creationists made you a rock star of science? Or would you have sought a place in the public eye anyway?

Lawrence Krauss: It’s hard to separate the chicken from the egg, or to say what specific events impacted on my trajectory. I’ve always been intensely interested in both public science education and public policy, as well as writing. I think it’s fair to say that the ID events in Ohio raised my profile as an advocate for science and reason. I can’t say I planned to be where I am today, but I can say I always admired people who accomplished things, asked questions, and spoke out, even on unpopular issues when they thought it was necessary. I suppose that admiration contributed to directing my own actions.

TheHumanist.com: At one point in the film, you tell Richard Dawkins that your approach has changed over the years. You used to try to meet people where they were and persuade them to follow you to the new place. Now, you advocate a much more confrontational approach. Why is that? You mention research, but I wonder if you have personal experience that shows it to work.

Lawrence Krauss: I think it’s important to be intellectually honest, and pretending that the doctrines of organized religion are compatible with the results of science is dishonest. Moreover, as I see the incredible attacks that occur even if you simply raise questions, I realize that we accord religion far too much respect and give it far too wide a berth in modern society. It needs to be ridiculed like we ridicule everything else.

TheHumanist.com: In one scene, you engage in debate with a young Muslim man before an audience that seems to consist entirely of Muslim students. Going into it you appear to be understandably nervous. Does the confrontation ever go beyond the exchange of ideas to the brink of threat? Do you sometimes feel that you could become the next Salman Rushdie?

Lawrence Krauss: I don’t really worry about that. The event shown in the movie was very collegial in many ways, so I wasn’t worried. It does seem amusing that the only places I have ever been assigned bodyguards are events where I’m debating religious apologists. That says something doesn’t it?

TheHumanist.com: You and Dawkins take a stand against religion generically. How do you define religion? Is there any form of it that you see as benign, or do you seek its complete extinction?

Lawrence Krauss: I don’t take a stand against religion. I take a stand in favor of reason and empiricism. To the extent that religion gets in the way of those important pillars, I hope it will become extinct.

TheHumanist.com: In the United States we see a paradox emerging. On the one hand, there’s a great exodus from religion underway. On the other hand, relatively few of those who are leaving religion declare themselves atheists or become activists, while the political influence of reactionary religion has rarely been greater, especially at the state level. Do you feel that you’re succeeding? Is there something missing from the movement that would assure its success?

Lawrence Krauss: I am not part of a movement, and I’m not advocating any beliefs. I am advocating open questioning, skepticism, and the importance of basing private actions and public policy on empirical evidence and reason.

TheHumanist.com: The documentary follows you and Dawkins to several countries. Where do you feel that your message was best received, and where is it most needed?

Lawrence Krauss: The Aussies have great fondness for us it seems. I think the United States is the most important place for the message because the United States exports so much to the rest of the world, both good and bad.

TheHumanist.com: You and Dawkins differ culturally. Apart from nationality, he wears what I take to be Oxfords; you favor sneakers—sometimes pink ones. He’s a hand-shaker; you are a hugger. Do such differences lead to awkward moments, or do they deepen your dialogue? (Or both?)

Lawrence Krauss: A thousand points of light; it takes all kinds 🙂 . I think Richard and I both enjoy our differences as well as our intellectual agreements. I believe we both respect each other’s knowledge and skills. I certainly respect his.

TheHumanist.com: Revolutionaries are often better at tearing down then building up. In the film you make several references to the insignificance of humanity, and at one point you speak of our miserable future. Do you have a concrete vision of a post-religious humanity, and, if so, it is hopeful?

Lawrence Krauss: No. Well, sometimes I envision a Star Trek-like future, where science leads to rational behavior, ends xenophobia and superstition, and so on. But again, I think a world where we better appreciate reality and open our minds to it can’t be worse.

TheHumanist.com: Recent evidence appears to strengthen the case for cosmological inflation, and by extension the case for eternal inflation in infinite multiverse. In the film, you speak at one point about certainties in science. Evolution happened, for instance. Leaving theology aside, how certain are you that the explanation for our universe lodges in the quantum laws writ large? Is there room for a creator—say, as Nick Bostrom has suggested, a mischievous high-tech teen running a simulation in his bedroom?

Lawrence Krauss: There is room for a creator, just as there is room for a china teapot orbiting Jupiter. It is highly unlikely, not suggested by any evidence, but an impotent creator with no real footprint cannot be ruled out.

TheHumanist.com: Taking that last question one step further, physicist Max Tegmark and others have argued that if the multiverse is infinite and infinitely variable, then there must be infinite copies of ourselves in every possible permutation. (Of course, Hugh Everett’s many-worlds interpretation leads to a similar conclusion.) If you accept that kind of thinking, it follows that an advanced civilization could deliberately create a universe fine-tuned to nurture life, and must have done so, infinitely many times. Until we know whether it is possible to do so or not, doesn’t this lead to an open question about whether our existence is chance or planned?

Lawrence Krauss: We cannot say there’s no purpose, we can simply say there is no evidence of purpose. And as far as multiverse claims are relevant, we can say that any such claims, without a probability measure, are rather sterile.

TheHumanist.com: And, finally, at the 2012 Reason Rally you addressed the largest crowd of rationalists yet to assemble, but The Unbelievers has the potential to reach many more. What are your hopes for the film?

Lawrence Krauss: I hope it starts conversations among people who haven’t thought of these issues. Not the converted, but those who can be provoked into questioning. In a test screening over 90 percent of those who claimed they were religious said they would recommend the film to a friend, and many who saw it said it led afterwards to an evening of discussion. My hope is that it can do so as broadly as possible.