The Many Intersections of Reproductive Justice

Excerpts from “Reproductive Justice and Intersectionality” presented by Dr. Colleen McNicholas and Pamela Merritt and offered by the American Humanist Association’s Center for Education this Spring.

BEFORE WE APPROACH what can be challenging issues for people to digest, we want to invite you to open your mind to concepts you might not be familiar with, or that you might have heard misrepresentations of, and the reality that your lived experience is not everybody’s lived experience. Your experience within healthcare might not be the same as someone else’s experience. Within the reproductive justice movement, we are organizing by centering the most marginalized within our communities, and sometimes that’s not you. If we aren’t open to receive a completely different narrative, then we will continue to do the exact same things and not make needed changes. People are human, so we want to make space for people to make mistakes as long as that is done in the pursuit of growth and education.

The reproductive justice movement is grounded in human rights and justice frameworks that mix with intersectionality in our work today. The human rights framework came out of the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which was introduced December 10, 1948, with different folks from around the globe and across specialties. Basic human rights exist in all areas of our lives: in our civil and political life, in our financial security, our social spaces, and our cultural spaces. The fundamental principle that came out of the human rights framework is that, not only are these rights present, but they are independent and indivisible. The Declaration itself includes thirty articles with topics like the prohibition on slavery, the right to have work that you choose, the right to enter and leave a marriage freely, and the right to create a family in the way that you see fit. The justice framework is about social justice activism and is built on the pursuit of access, equity, participation, and human rights. It applies to reproductive rights, healthcare access, education access, employment discrimination, voting, and disability.

It’s important to distinguish between the concepts of equality, equity, and justice. Equality is the assumption that everyone benefits from the same support and thus they deserve equal treatment. Equity means that everyone gets the support they need and that support might be different for me than it is for you. Justice is when everyone has the support they need because the causes of inequity were addressed, meaning the systemic barrier has been removed rather than using a temporary fix in place. Intersectionality is a critical tool that we use to make sure that we are achieving justice, a permanent or substantial change to empower those being oppressed to become liberated. It challenges us to realize that we might have privilege in some spaces and not have privilege in other parts of our identities. It makes us acknowledge all of the intersecting ways that people experience oppression. By centering the most marginalized and building solutions, policies, and actions around liberation, we can support everyone in a more compassionate society. Using this tool pushes medical professionals to more fully understand their clients’ needs, based on the many aspects that make up who we are, such as gender expression, religion, occupation, nationality, sexual orientation, age, culture, race, mental health, ability, and so on.

Intersectionality is a critical tool that we use to make sure that we are achieving justice, a permanent or substantial change to empower those being oppressed to become liberated.

The old, siloed way of thinking caused coalitions to form and work separately, seeing reproductive rights—or “choice”—apart from other issues like immigration rights, criminal justice, etc. The reproductive health lens takes a person’s demographics into account to understand the impact on one’s health, but the health plans are very focused on the delivery of service (i.e., what is the health care that I’m trying to get to that person). The reproductive rights lens, which oftentimes works in parallel with the reproductive health lens, is much more focused on the legal rights of an individual to have an abortion or to continue a pregnancy. One’s right to an abortion is not at all about pregnancy or healthcare, instead, it is grounded in a legal decision about privacy as seen in the initial Roe v. Wade decision. Instead of bringing everyone together over reproductive justice, both of these approaches ultimately fall short of fixing the problem.

Reproductive justice was developed by Black women who had gone to Cairo for a conference in the 1990s and were disappointed with the siloed work we just described above. They returned to the US to integrate reproductive rights, social justice, and human rights by founding the African American Women Illinois Pro-Choice Alliance Caucus, which has since birthed some of the strongest national organizations on reproductive justice. They advocate for the human right to decide if and when one will have a baby and the conditions under which to give birth, to decide if one will not have a baby and the options for preventing or ending a pregnancy, and to parent the children that one already has with the necessary social supports and environments that are free of violence and oppression. The reproductive justice framework is based on intersectionality and the practice of self-help. People need to not only have the legal right to abortion, but also have access to abortion which includes the number of clinics available, the number of professionals prepared, the insurance coverage, and other barriers. It challenges us to examine how our bodies are controlled and requires multi-issue cross-sector collaboration.

We encourage people to feel confident showing up to different justice movements with an eye towards reproductive justice. Here are some examples:

Economic Justice: What is reproductive choice if you don’t have economic power? When there is a fight for raising the minimum wage, reproductive justice should be at the table. If what’s driving you to choose abortion is that you don’t have financial security, then the solution is an economic one. Affordable childcare, equal pay for equal work, and paid family leave are obvious ways that economic justice and reproductive justice intersect, but it hasn’t been until very recently that the reproductive justice folks have had a seat at that table.

Immigration Status: You have probably heard of the nearly sixty women who were in immigration detention centers at the border and reported being coerced into having hysterectomies—fertility-ending procedures. However, a potentially less obvious thought is how being undocumented in this country impacts day-to-day life, making people much less likely to report incidents of domestic violence. Any interaction that might bring the attention of law enforcement is essentially avoided. Lots of folks who are pregnant and in situations of domestic violence are unwilling or unable to obtain the necessary resources for birth control or abortion services. Many of those who may continue the pregnancy are unable to access prenatal care for the same reasons, which in turn makes their pregnancies less healthy and potentially impacts pregnancy and birth outcomes.

Political Representation: Political representation is most certainly a reproductive justice issue. We believe that every person has a human right to be represented. However, even though “no taxation without representation” has been drilled into our heads, not everyone is truly represented by their elected officials. We have a big problem, not just in our federal government, but in our state and local governments as well. When we consider the discussion of infant and maternal mortality in the state of Missouri, where Black women are three to four times more likely to die as a result of pregnancy complications in the first year after giving birth, the challenge to get policymakers to amplify this issue is obvious. Luckily, it’s beginning to get easier because representation is expanding. When we think about where the hurdles are in dealing with reproductive justice and poor birth outcomes, we see that many are based on the fact that those with political power have no idea what it’s like to live as a woman of color, as a native woman, or as a trans Black person.

Gender and Sexuality: Due to the legal right to turn away trans people in many places, some have difficulty finding an OBGYN with whom to address an array of issues including conversations about fertility or treatment of ovarian cancer. We are starting to see vibrant discussions about what providers and physicians need to know about the wonderful spectrum of gender and sexuality. We believe that all people have a human right to healthcare, and certainly there is a human right to build families, and these shouldn’t be rights that are out of reach based on providers’ individual discrimination.

Police Violence: Police violence is often talked about in terms of denying families or mothers the right to parent their children. The second most common police misconduct complaint is sexual assault and sexual harassment. The more marginalized an individual is, the more likely they will be confronted by this kind of situation, which extends to undocumented people, sex workers, and trans folks. There is also violence against Black and Brown women who are experiencing the toxic stress of raising children or facing the decision to have children at all in a society that is often indifferent toward Black children being brutalized, terrorized, harassed, and killed.

Now that we see how reproductive justice is interconnected with other societal concerns, it’s important to review societal trends to understand where reproductive justice currently stands. We have seen an overall and ongoing decline in abortion since 1980, which is probably due in large part to increased access to and use of contraceptive methods. One may believe that abortion is on the rise, but the reality is that the rate of abortion has continued to decline over time for all age groups.

The intersection of abortion patients is what should drive our advocacy and how we fight for reproductive health rights and justice. One in four people who are capable of pregnancy will have an abortion in their lifetime. It is likely that within your family and workplace, multiple people have had or will have an abortion. Sixty percent of people who have had abortions are already parents. The majority are in their 20s, but the age range spans from early adolescence to much older. (The youngest person we have ever taken care of was nine and the oldest was fifty-two.) Most identify as heterosexual and have some sort of religious affiliation. Seventy-five percent identify as having financial insecurity. This is important because as reproductive justice advocates we have to be on the front line of the $15/hour (or more) minimum wage fight. From this data pool, thirty-four percent of individuals seeking an abortion identify as White, twenty-eight percent as Black, and twenty-five percent as Hispanic, suggesting there isn’t just one type of person who needs or seeks an abortion. This also suggests there isn’t one single issue that is more deserving of attention than another. Reproductive justice advocates must be present in all of these spaces. As Audre Lorde said, “There’s no such thing as a single-issue struggle because we do not live single-issue lives.”

Roe v. Wade is a landmark Supreme Court ruling that is based primarily on privacy rights. However, once the ruling was made, it basically decriminalized access to abortion throughout the entire country. Despite some valiant efforts within the past forty-eight years of activism, we are looking at a Supreme Court with a majority who do not believe or agree with the Roe v. Wade decision. The Roberts Court is looking to gut Roe, most likely to set abortion rights back decades in the States, and the only question they’re currently contemplating is which of the many direct challenges to Roe from state legislators they want to take on. [Note: Since this discussion was recorded the Supreme Court has agreed to hear Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization.] By the end of February 2021, 384 anti-abortion bills were introduced in state legislatures and two states had passed all-out abortion bans that are currently enjoined (there is currently no state in which an abortion ban is officially enacted). About twenty-one states have laws that would likely be used to restrict legal access to abortion, and nine states have strong, unenforced, pre-Roe abortion bans that would kick into gear.

The loss of clinic-based and legal abortion care does not come with the automatic risk of death. A lot has changed since 1973, and the biggest risk of Roe falling is that somebody will go to jail. Many states already have laws that would criminalize providing an abortion. When medication abortion is carried out without a physician and outside of medical care, the individual becomes the abortion provider, and they would go to jail. If Roe fell, we would see people being incarcerated and in some states facing the death penalty for abortion.

I hope the next time we are present in a social justice space, we will each bring up a reproductive health issue, a birthing issue, an abortion issue, a contraception issue. I hope we will each find a way to bring reproductive justice to the table.

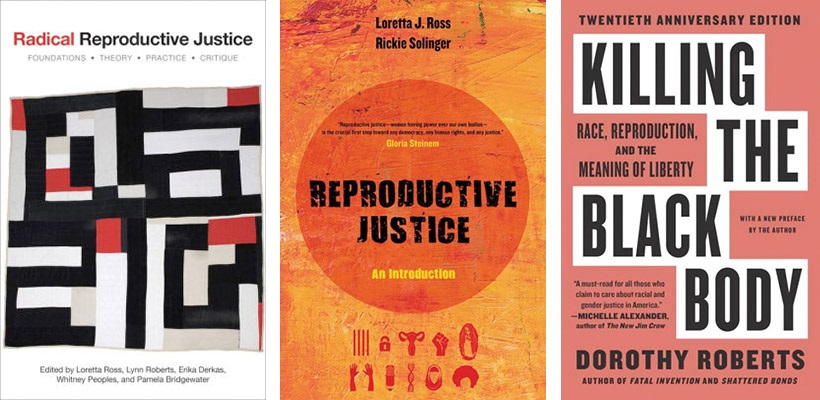

Read More about Reproductive Justice

Radical Reproductive Justice: Foundations, Theory, Practice, Critique. Edited by Loretta J. Ross, Lynn Roberts, Erika Derkas, Whitney Peoples, and Pamela Bridgewater Toure

Reproductive Justice: An Introduction. By Loretta Ross and Rickie Solinger

Killing the Black Body: Race, Reproduction, and the Meaning of Liberty. By Dorothy Roberts